An Alaska Medicaid program that funds care for developmentally-disabled adults may be reducing the number of people it enrolls each year by 75 percent.

Medicaid’s Intellectual and Developmental Disability waiver pays for the home-based care of 1,928 people in the state whose disabilities are severe enough to require 24-hour care — those who would otherwise be treated with permanent hospitalization or institutionalization. The number of waivers has increased by 860 over the past eight years, according to a notice by the Alaska Governor’s Council on Disabilities, but demand for waivers far outpaces the state’s ability to process applications.

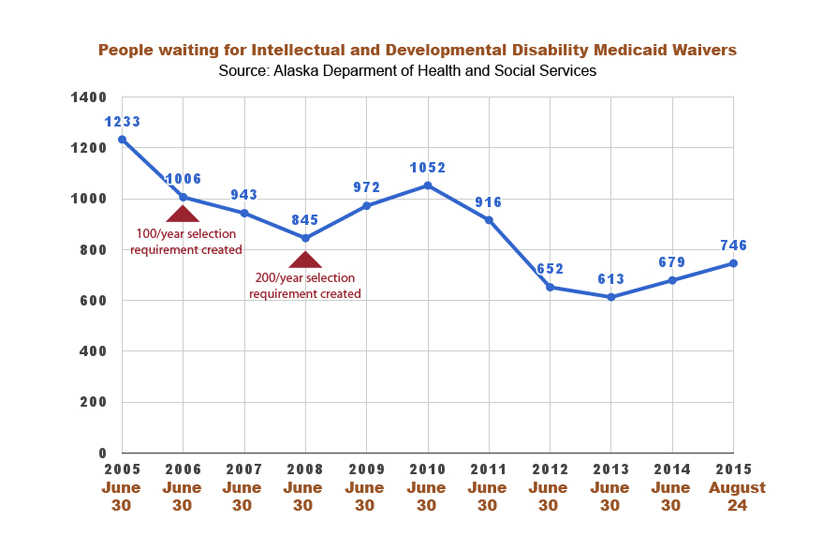

Unprocessed applications join a registry, known officially as the Developmental Disability Registration and Review, but referred to by those on it as “the waitlist.” In 2008, the state legislature mandated that 200 wait-listed people would be granted waivers each year. Recently, the waiver program’s administrators have proposed lowering that annual number to 50.

As of August 25, the waitlist contained 746 names, although Program Chief Lisa McGuire of the state’s Senior and Disability Service Division, the entity that manages the waiver program, said the number flucuates daily. Approximately 52 of those people are on the Kenai Peninsula.

Prior to 2006, there was no annual requirement for selecting people from the waitlist, which in 2005 contained 1,233 people, according to the program’s annual report to the state legislature. McGuire said, at that time, the only selections made from the list were to replace users who died or left the waiver program. Under pressure from activists, the legislature instituted an annual selection requirement of 100, which was raised to the present 200 in 2008. By 2012, the waitlist had dropped to 652, and has since remained between 600-700.

Kathy Fitzgerald is a member of the Key Coalition, one of the developmental disability advocacy groups that campaigned for the selection requirement. Her severely autistic daughter, Kara, is presently receiving service through the waiver program. Fitzgerald said after making 200 annual selections from the list for seven years, the requirement has made a non-numerical difference as well.

“We are finally getting down to where it’s no longer just individuals or families in crisis that are selected off the waitlist,” Fitzgerald said.

She described the criteria for being chosen from the waitlist as “really a triage kind of tool.”

“It’s looking at ‘who are the people we’re waiting to death, that we have to get off now?’” Fitzgerald said.

Maureen Harwood, manager of the state’s Intellectual and Developmental Disabilities Unit, said those on the waitlist are ranked according to a series of weighted questions designed to quantify the urgency of a case. The questions address the categories of community participation, living situation, and caregiver concerns.

“What are behaviors that are causing you to have less access to the community?” Harwood said, giving examples of these questions. “What are self-harming things you do? Is your guardian getting near an age where they are no longer able to support you? Have you been in an institution like jail, or various places?”

Harwood said homelessness is also a factor assessed by the questionaire.

It is possible for an individual to have needs that qualify them for the waiver, while having a zero score on the urgency questionaire that determines waitlist rank. Harwood said 24 percent of those on the waitlist have zero scores.

For the monthly selections from the waitlist, Harwood said “we always draw by the highest points.”

Kara Fitzgerald, who is non-verbal, spent three years on the waitlist. She is now in her early 30s, while Kathy Fitzgerald is in her late 60s and recently had a surgery that prevents her from helping Kara bathe. That task has been taken over by an aid-worker paid through the Medicaid waiver program, who also helps Kara get out of the house, where “she volunteers at two or three different places in the community,” Fitzgerald said.

Fitzgerald said families in situations similar to her own — difficult, though not a crisis — had been benefitting from a high annual selection requirement, which allowed non-emergency cases to receive waivers after the higher-priority emergency cases had been drawn. She said such cases would be less likely to receive waivers if the selection requirement was reduced to 50.

“Maybe their child is graduating from high school, for example,” Fitzgerald said. “There are no mandated services after high school. Maybe you’re looking to apply for a waiver so their life can continue, so they’re not just sitting at home losing skills. Well, that’s not really a critical issue… Families are concerned that this (the reduced annual selection requirement) is going to put us back in a crisis-driven situation.”

Some agencies that provide service under the waiver program have officially supported the reduction. One of these is Hope Community Resources, whose executive director Roy Scheller said the selection requirement reduction “just means that everything is slowing down.”

“All citizens are going to have to help them balance the budget,” Scheller said. “Some people, their kids are in bigger classrooms. Some communities have less police and fire protection… I’ve always taken the position that people with intellectual disabilities are also citizens of Alaska. So I’m not going to say that they’re citizens when they need something, but not citizens when they have to give something.”

Harwood said the waivers had cost $160 million in fiscal year 2015, a cost split halfway between the state and federal Medicaid programs. The money spent on individual waivers varies, and has no cap.

“We have some waivers that are up in the $300,000 range,” Harwood said. She said $85,000 was the average yearly cost of a waiver.

Harwood said a requirement to add 50 people to the waiver program each year would not necessarily limit the program to an increase of 50 per year. In addition to the annual 50-person increase, wait-listed people would also be added to replace waiver recipients who move out of state, die, or leave the program for other reasons.

Scheller said the reduced requirement is a reasonable reaction to the state’s financial situation.

“We’ve been taking off 200 people a year, and the list isn’t shrinking,” said Scheller. “More and more people are coming on. From a state perspective, then, there’s a lot of people who have needs out there. How do you meet those needs at a time when the price of oil has dropped under $40 a barrel?”

The Key Coalition’s Kenai Chapter president Dennis Haas said his group’s official stance on the proposed reduction would be determined at a Sept. 11 statewide meeting, but as an individual, he said that by making a 75 percent reduction in the 2008 selection requirement, the state had “decided to renege on that promise.”

“I know times are tough,” Haas said. “If they would say to us ‘this year we’re only going to draw 50, but next year we’ll do 100, and the year after 150, and we’ll try to get back up to 200,’ we could live with that. But to just arbitrarily cut it down to 50 without any hope for the future, I don’t think that’s fair.”

The Alaska Department of Health and Social Service’s Senior and Disabilties Services Division will take public comments on the proposed reduction until Sept. 17. McGuire said if the state decides to adopt the change, it would likely be instituted this fiscal year — before June 31, 2016.

Comments can be sent by email to iddunit@alaska.gov.