Fish have played a major role throughout Kasilof’s history.

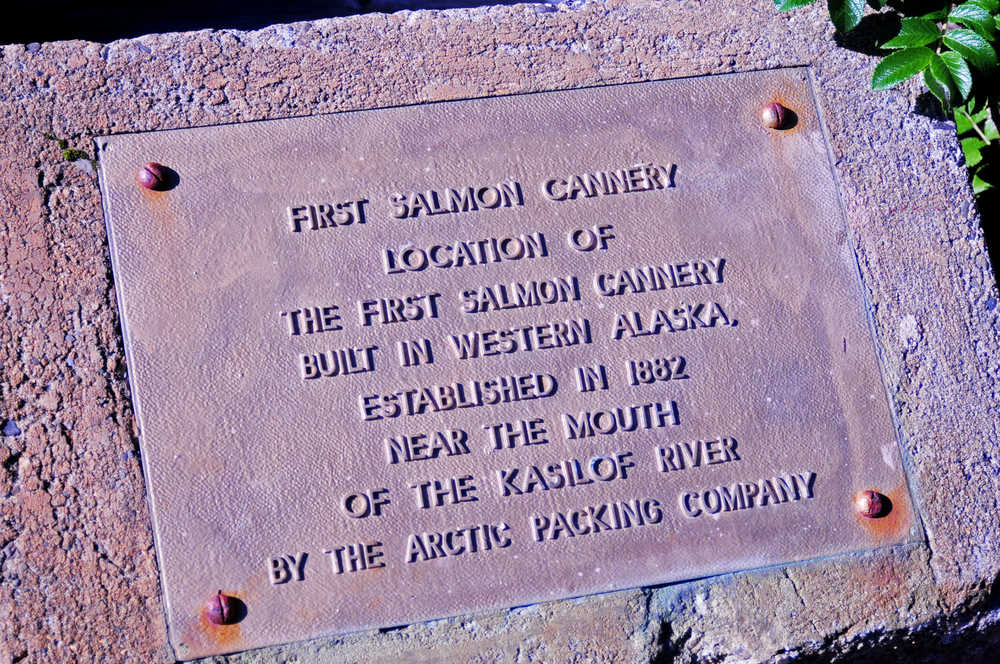

The Dena’ina people fished and lived near the mouth of the Kasilof River for generations. The first cannery in Cook Inlet, the second in Alaska, was built on the Kasilof River and operated there from approximately 1882 until 1938. Fish traps, which were controversially used by commercial processors and ultimately banned after statehood, were spaced out between the mouth of the Kasilof and Kenai rivers.

Today, the river is home to all kinds of fishing, from private sport anglers to guided operations to personal-use dipnetting and gillnetting at the mouth, as well as the existing commercial operations that enter the river to deliver fish at the buying stations there.

Sport and personal-use has grown significantly, and the mouth of the river is packed with people from approximately June 15 until Aug. 7 each year, when the personal-use fishery is open for Alaskans to come and collect salmon. Effort on the Kasilof River personal-use dipnet fishery has increased significantly over the years, peaking in 2015.

To support the increasing use in the personal-use fishery, the Alaska Department of Natural Resources’ Division of Mining, Land and Water is planning to install infrastructure for the first time. The plans include improving the existing north beach access road and installing turnarounds, fences and a 132-space paved parking lot. The parking lot will have dumpsters and portable toilets each summer and a space for law enforcement to park, according to the plans.

The state will take bids on the project, estimated at between $1 million and $2.5 million, until Sept. 16, and will have 40 days after that to review bids before making a decision.

Throughout the process, residents have had questions and concerns about the impact of development in the area. Kalifornsky Beach Road area resident Ken Tarbox said he is primarily concerned about the effect on migrating birds because of habitat disturbance and potentially increased use. Kenai’s city government was able to handle the personal-use fishery there, but the Kasilof did not have a local government and the lack of regulation has resulted in habitat damage in the area over the years.

“The failure occurred when the fishery started,” Tarbox said. “If we’re going to create fisheries, we should create the infrastructure to support that, otherwise we’re going to have vast habitat damage.”

He credited the Division of Mining, Land and Water for responding to public comment and concerns. He said there are still steps to be taken, though, to ensure development is “a win-win” — the Division of Mining, Land and Water has no regulatory authority to stop someone from camping in the dunes, even if they put up fencing, or the authority to charge fees to support the infrastructure. Tarbox said he would also like the state to review the possibility of seasonal use restrictions to minimize disturbance.

Others are concerned about the pavement. The original project plans proposed a gravel parking lot, but the final plans indicate pavement. Christy Colles, one of the state natural resource managers working on the project, said in a previous Clarion interview that planners decided on pavement because of future maintenance concerns.

Catherine Cassidy, a Kasilof resident who works with the Kasilof Regional Historical Society, said although she was happy the state scaled back its plans, she was disappointed with the pavement because of the potential for polluted runoff into the wetlands and the damage from heaving.

“It seems kind of crazy to be building that in a place that’s going to heave,” Cassidy said. “Once they pave it, they’re stuck with it.”

Though fisheries have been present on the Kasilof for a long time, with a cannery and its outbuildings parked on the riverbank for years, there is no precedent for the dipnet fishery. It is a relatively new fishery, created by the Board of Fisheries in the 1980s. The story of access in the area has changed in the past few decades with the addition of roads rather than water-based transportation as well, which is important to remember, Cassidy said.

“It’s such a paradigm shift,” she said.

Potentially damaging the rich history of the area with a parking lot is a huge loss when it could be excavated and displayed for Alaskan history, said Alan Boraas, a professor of anthropology at Kenai Peninsula College.

He suggested modeling the Kasilof River’s access after Kenai, where people drive down on a dirt road, drop off their equipment and drive back to the uplands to park. It’s less convenient but would conserve the historical resources in the area, which take time and money to excavate.

“What we have done is not developed our history in a way that makes it accessible to people,” Boraas said. “This would be a remarkable historic site as well as a fishing site. This would be a great historic center to tell a lot of the story of this part of the Kenai Peninsula. And it’s not going to be as easily done if you have this big parking lot on top of it.”

Reach Elizabeth Earl at elizabeth.earl@peninsulaclarion.com.