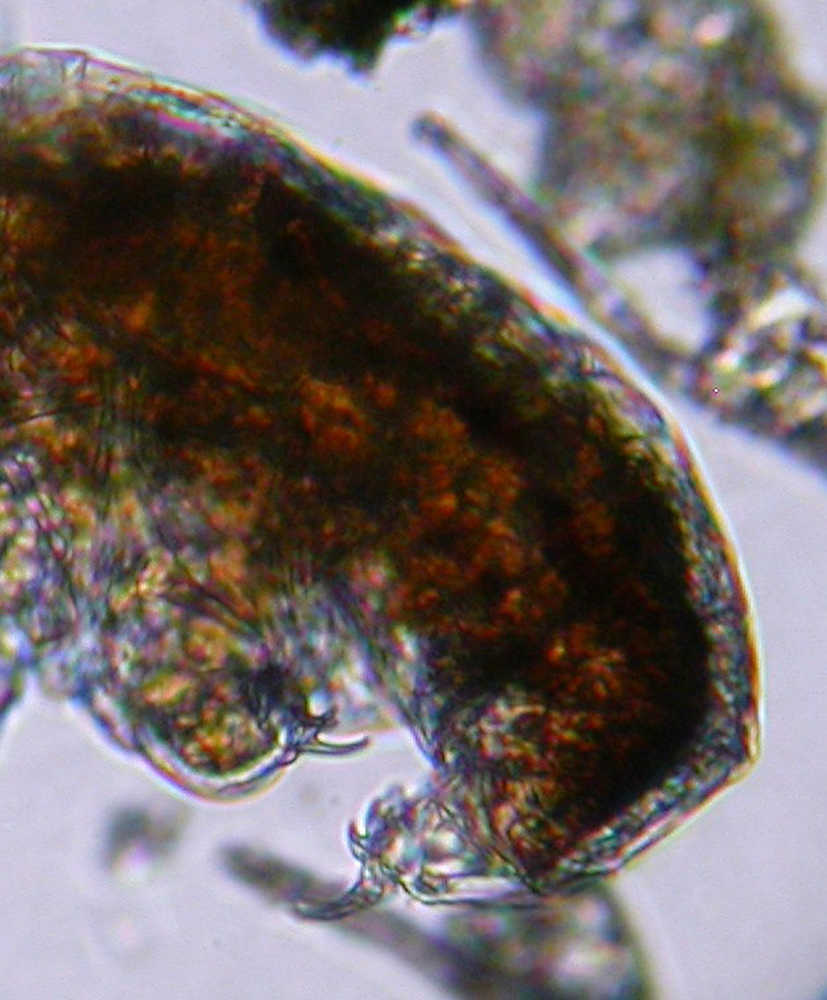

Mosses and lichens are among the most abundant plants on the Kenai Peninsula, both of which contribute to the ecosystem on a large scale. But at the microscopic level, they are home to an astounding number of organisms, including an invertebrate called a tardigrade and, in some circles, a water bear or moss piglet. They have eight legs with complex claws at the apex of each, and are slightly smaller than the period at the end of this sentence.

The photographs may make them look agile but, in reality, they bumble around their environment slowly and use their claws to hold on to the debris that is often found in moss or lichen. The slightest current can pull them away, and their claws don’t work well as boat paddles, making swimming difficult. In fact, the name Tardigrada means “slow stepper.” Quite coincidentally, it was given that Latin name in 1776, a special year that we celebrate every 4th of July.

Perhaps the most fascinating feature of the tardigrade is their ability to enter a hibernation stage known as cryptobiosis. During adverse environmental conditions such as drought, flood, and changes in air pressures, they can put all their biological processes on hold like a pause button. In times of drought, they shrivel up like a microscopic raisin and can stay like that until water levels return to normal, sometimes for 30 or more years!

During floods, the opposite happens. They swell up like a balloon and bounce around safely until water recedes. This is an important adaptation because at the microscopic level even the slightest change in temperature or water can drastically affect its inhabitants. Without the ability to enter the cryptobiotic stage, tardigrades would likely be extinct.

Tardigrades are considered “extremophiles” which means they live in the most extreme places on earth. They have been found on mountain tops where cold winds and low pressure are common companions. They are also in deep sea vents that spit out sulfuric acid and boiling water. But they don’t just call those places home — they can be found in freshwater streams and lakes, saltwater flats, estuaries, and in leaf litter on the ground. They are most commonly collected on moss and lichen because of the ease of collection, and because they can be found right in your backyard.

I collected a small sample of caribou lichen in the woods just behind the Kenai National Wildlife Refuge’s Headquarters on Ski Hill Road. I put it in a dish of water overnight to see what species of tardigrade lived in the area. Almost immediately after placing the slide under the microscope, I spotted a tardigrade crawling around on debris. Beside tardigrades, I observed mites, rotifers, and nematodes, truly a diverse community. Both tardigrades I collected and identified were from the genus Macrobiotus, which is the most common genus in Alaska. Unfortunately, identification to species requires high powered microscopes and, in some cases, the specimen’s eggs.

What do tardigrades do? This is a tricky question, and one I get asked often. It is important to know the purpose of organisms and research. I had a professor call it “taking up space.” All organisms take up space, and tardigrades are no exception. They eat rotifers and nematodes, which are also common microorganisms. Tardigrades exist in many unique microscopic habitats which might have different inhabitants without the predation and competition for resources posed by tardigrades.

Tardigrade research is an ongoing effort by biologists and even researchers at NASA. In 2007, NASA launched two colonies of tardigrades into space to take a closer look at how radiation affects living cells, searching for possible enhancements to manned space missions in the future. Not only were they the first organism to survive the vacuum of space and sub-zero temperatures, tardigrades also showed an ability to decrease the effects of solar radiation and oxidative stress — a potential cause of many human diseases including Parkinson’s and Alzheimer’s. There is continued research on tardigrades in space, and they are a common addition to most space missions.

Although we don’t know much about their life cycle or their ecology, they could be valuable in unforeseeable ways. So take a look in your backyard — odds are it is teaming with life and almost certainly tardigrades.

Rebekah Brassfield is a biological intern at Kenai National Wildlife Refuge. She is an undergraduate student at Concordia University in Nebraska, majoring in Conservation Biology. Find more information at http://www.fws.gov/refuge/kenai/ or http://www.facebook.com/kenainationalwildliferefuge.