By Clark Fair

For the Peninsula Clarion

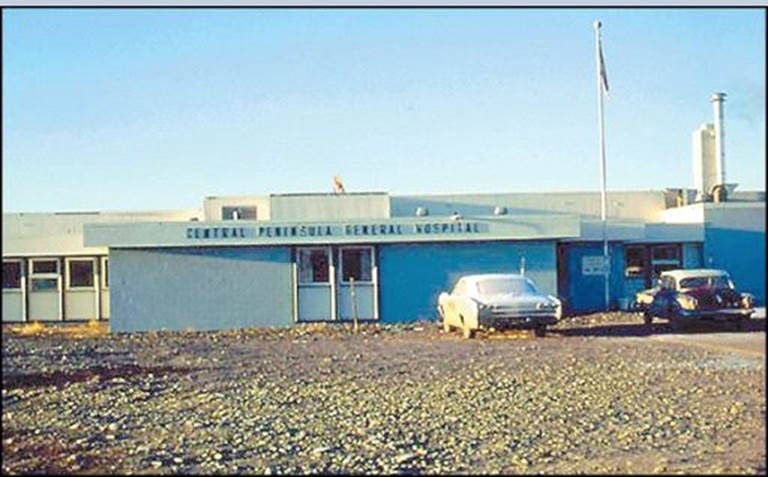

Author’s note: This is the final part of a six-part series about the origins of Central Peninsula Hospital, which celebrates its 50th anniversary in June. Earlier parts of the story outlined financial and political battles between Soldotna and Kenai and between hospital promoters and fundraising agencies. By the middle of 1967, work on the hospital, an idea conceived in 1961 and on which construction had begun in 1966, had stopped. Pressure was building from myriad sources to finally find a way to finish the job or give up entirely. Read Part 1, Part 2, Part 3, Part 4 and Part 5 here.

Government intervention

At 8:14 a.m. on June 21, 1971 — nine days after an open house and dedication ceremony — Central Peninsula General Hospital signed in its very first patient, an obstetrics case that led to the first baby ever born in the facility — Dustin Lee Poole, delivered by Dr. Peter Hansen, a Kenai-based physician.

In its first two weeks of operation, the hospital had 53 cases for its emergency room, 14 obstetrics cases, and four babies born — for a total of 71 patients.

The initial hospital staff included four physicians (Hansen, Paul Isaak, Elmer Gaede and Elaine Riegle), 15 registered nurses (under director of nursing Pat Severe), six licensed practical nurses, anesthesiologist Alfred Gelinas, two lab technicians, one x-ray technician, and about 20 auxiliary personnel. According to hospital administrator Gene Wheeler, the room rate was $70 a day, and the hospital payroll alone was expected to pump at least $30,000 to $40,000 a month into the local economy.

During 1972, its first year of existence, CPGH had had 3,185 patient visits. By its 20-year anniversary in 1991, the number of beds had more than doubled, the hospital staff was 10 times larger, and the number of physicians serving the facility had climbed to 25, the number of nurses to 59. Via three expansions and renovations, the hospital’s footprint had expanded from 8,000 square feet to 101,000.

The hospital, it was obvious, had been a smashing success.

But just four years before Dusty Poole’s mother-to-be walked through the doors, the hospital had been in big trouble, its very existence in grave doubt. Hospital promoters, who had spent six years fighting for funds and against each other, had finally started in construction in the fall of 1966, but by early 1967 the whole project was falling apart.

The Small Business Administration had promised the Peninsula General Hospital Association (PGHA) a loan of $350,000 for what had originally been billed as a $400,000 project. But when the PGHA chose a new architect and builder, the price jumped to $582,000.

When local fundraising efforts flagged, building plans were scaled back to reduce the price.

The SBA finally began issuing funds in late December 1966, but there was only enough money to pay off work already done, not enough to actually finish the job. No completed hospital meant no new income and no way to reimburse the SBA. All bids and orders for equipment and other materials were allowed to lapse. Work stopped.

The building sat empty. Estimates ranged from the hospital being 60 percent to 75 percent complete, but no one debated whether it was a usable facility.

It was not.

The SBA began to threaten foreclosure. An SBA spokesman tells Soldotna’s Dr. Isaak that the spokesman “has it within his power to do anything with the hospital that he [wants]. He said he could give it away, or sell it for any amount of money that he felt he could get.”

The Kenai Peninsula Borough, only three years past its founding, began to seek solutions. Talks began concerning the establishment of a service area to fund the completion and operation of the hospital.

Soldotna City Council member Justin Maile wrote to regional SBA director Robert Butler to plead the hospital’s case. If the SBA withdrew its support, he said, any hope of ever getting an area hospital could be doomed.

A group of Kenai and Nikiski residents disagreed. They sent a representative, Norman McGahan of Nikiski, to the borough assembly meeting on Aug. 1, 1967, to present a 23-signature petition and ask for a special borough election to decide whether Kenai-Nikiski could form its own hospital service area and levy taxes on real property for the purpose of erecting a general hospital.

At a hearing held later that month, the borough attorney said the Kenai-Nikiski plan could cost $800,000, and he urged the plan’s proponents to order an independent feasibility study and to demonstrate stronger public support by seeking more signatures on their petition.

By April 1968, the Kenai-Nikiski plan had lost momentum. Even the Kenai City Council had refused to support it, and Kenai mayor Bud Dye, speaking on his own behalf, urged people to “back the Soldotna hospital to see if we can get it completed and going.”

Meanwhile, with the SBA loan still in default and the central peninsula population climbing past 12,500 residents, periodic inspections at the unfinished hospital generated lengthy to-do and to-repair lists that ballooned costs.

Hospital promoters elicited help from state and federal legislators. Under political pressure, the SBA agreed to delay foreclosure if the hospital association submitted a firm proposal for reimbursement and a completed hospital.

But the SBA debt itself was an albatross. Other potential lenders were hesitant to loan money to a borrower incapable of paying its debts. And local fundraising efforts had no hope of generating the necessary cash.

In September 1968, borough chairman Harold Pomeroy wrote to Harry Malm, executive director of the Lutheran Hospitals and Homes Society of America, to gauge that organization’s interest in taking over the hospital project. Malm, who had been corresponding for years with hospital-project founder Dr. Isaak and was well aware of the problems, wrote back to say “no thanks” because he felt that the local public’s financial stake in the hospital was inadequate.

“One of the hard facts of life of the hospital profession,” Malm wrote, “is that there is no magic money tree which can be shaken to produce funds needed for hospital construction. Federal programs require local participation because the first responsibility for health care lies with those who will be directly benefited.”

Pomeroy concurred. He negotiated with the SBA to postpone foreclosure, knowing that liquidation of the property would bring pennies on the dollar and sink all hope for a hospital in the near future. He also did not want the borough to lose property he believed could have a value of at least $1.4 million once the hospital was completed.

The SBA pushed back its plans for a foreclosure sale to February 1969.

Over the next several months, the borough established the outline of a central peninsula hospital service area, which it planned to put on the ballot in a special April election. The city of Homer, also seeking consistent hospital funding, asked and received permission to create a service area of its own and put it on the ballot at the same time.

In addition, the borough tentatively scheduled a separate October bond election to ask whether service area voters were willing to assume the $350,000 SBA debt. The news of these elections encouraged the SBA to again postpone its foreclosure plans.

In April, voters agreed to establish both new hospital service areas. The vote for the central peninsula was 735 yes, 470 no. In early October, voters agreed, 1,356 to 404, to tax themselves to pay off the SBA.

On Oct. 28, 1969, the PGHA used a Quit Claim Deed to transfer its property to the borough, which was then obligated to complete the project before turning over its operation to a professional entity — in this case, the Lutheran Hospitals and Homes Society of America.

The borough would eventually spend $870,000 to complete the facility and make it operational.

Milt Eckhaus, the California-based hospital designer-builder whom Isaak had befriended many years earlier and who had believed that his original plans and workers would one day make the hospital dream come true, wrote to Isaak in January 1970: “I know how much it means to you [to be nearly finished with the hospital]. I also know the time, effort and ‘costs’ you have expended. I sure hope that the community at least says ‘Thanks’ to you.”

Isaak appreciated the sentiment, but he was incensed that the “extra” costs — of revisions, equipment purchases and the additional construction necessary to complete and outfit the facility — were double what Eckhaus had proposed in 1962 as a total price tag. “This whole situation makes my blood boil every time I think of it,” he wrote, “and that is quite frequently.”

In 2003, Central Kenai Peninsula Hospital Service Area voters approved a $49.9 million bond sale to expand and renovate Central Peninsula General Hospital. Five years later, after all the work had been completed, a grand opening for the newly christened Peninsula General Hospital was held.

The facility was edging toward 200,000 square feet, and Soldotna was firmly positioned as the center of the medical establishment for the central Kenai