AUTHOR’S NOTE: In the first two parts of this story, William Dempsey, who had murdered two Alaskans in 1919, escaped from prison in Washington in 1940, sending a chill through the man who had sentenced him to death. Dempsey’s victims and his trial judge were also introduced. Part Three examines the killer himself.

Web of Convergence

The lines of history are most accurately understood in retrospect. Marie Lavor, for instance, could not have known that the man who would kill her in Anchorage in 1919 would be born in Cleveland, Ohio, during the same year, 1900, that she emigrated from France to the United States.

Isaac Evans, who married in 1900 and a few months later began working in western Alaska, was likewise unaware that the same killer would cross his path in Seward in 1919, with equally fatal consequences.

And Charles Bunnell, who started a career in education near Kodiak in 1900, had no idea that the judgeship he was appointed to in 1914 would send him, five years later, on a collision course with the same killer in a courtroom in Valdez.

These intersecting lines could be perceived only after the fact, after these three lives had become entangled in a web of violence and deceit spun by a man known as William Dempsey.

Dempsey’s origins, which were decidedly cloudy in 1919, have failed to clear significantly with the passage of another century.

His true story was blurred, first of all, by at least a half-dozen aliases, including William Cummings, William Stewart, Jack Smith and Jack Nichols. Even “William Dempsey” was not the name he was born with.

He confessed to authorities after his arrest in Seward that he had begun using false identities in order to avoid being drafted during World War I. But even that admission was untrue.

Most likely, he was born as William Demski (possibly Dempski or Dembski) to Polish-immigrant parents, Joseph and Emily, on Jan. 14, 1900, in Cleveland. He was, according to information gathered in 1919 by the Cleveland Police Department, one of seven children — four girls and three boys. The two older sons, John and Stanley, were already married when the police came to call.

At the time of the investigation, the Demskis were living at 7612 Spafford Road in Cleveland and had resided at that address since at least 1916. The parents had been informed of the murder charges against William, and they positively identified their son from a photo of him sent to Cleveland police by authorities in Alaska.

According to the police report, Joseph and Emily Demski claimed that William “was never in any trouble” as a boy. In about 1910, they said, he had been struck in the head by a keg falling off a wagon and had complained afterward about dizziness. Furthermore, he had quit school at age 14 and left home to work on farms in other parts of the country before returning to Cleveland in 1917 to see his parents.

After a short time at home, he had announced his intention to move to Alaska. No one in the family, said the Demskis, had seen William since he headed north. Their only communication with him had been two picture postcards, one sent from Juneau in November 1918, the other from Anchorage in February 1919.

U.S. Census reports from 1900 and 1910, however, reveal no member of the Demski family named William, nor any family member born in 1900. To be sure, census records contain inaccuracies, and there were other Demski families in Cleveland.

In fact, Polish people, who began arriving in Cleveland in large numbers in the late 1860s, formed one of the city’s biggest ethnic populations during the 20th century. But only one Demski family lived at 7612 Spafford Road at this time, and that family claimed William for its own.

It is possible that even his given name, “William,” was not his true birth name. He may also have been born a year earlier than reported by his parents. There was, for instance, a Vincent Demski (or possibly Dembski), born in 1899 to a Dembski family in Cleveland. That Vincent—along with older brothers John and Stanley—appeared in both the 1900 and 1910 census counts in Cleveland, and then disappeared.

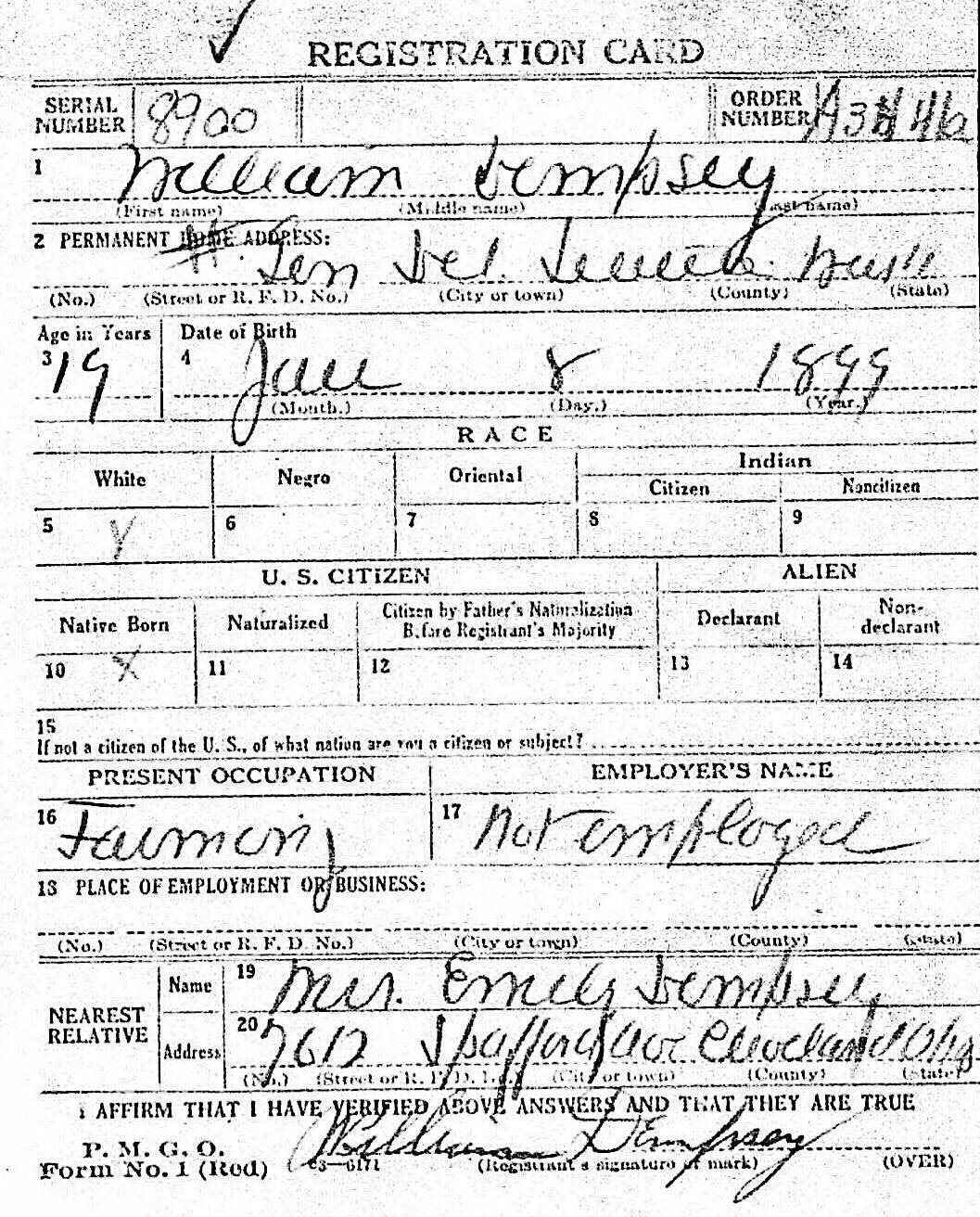

When William signed his draft-registration card in Seattle in 1918, he provided 7612 Spafford Road as his home address. He also claimed that his last name was Dempsey and that his nearest relative was “Mrs. Emily Dempsey.” His birthdate was listed as Jan. 8, 1899, with an age of 19.

Ascertaining the full truth about these origins is also complicated by the fact that William Dempsey, when interviewed by authorities after the killings in Alaska, frequently lied about his history, his whereabouts, and his motivations. After his arrest in Seward, he claimed that he had fudged his true identity and certain facts about his childhood in order to protect his parents and keep them from being humiliated by his actions.

On Sept. 5, 1919, with Dempsey in the federal jail in Seward, Charles E. Herron, editor of the Anchorage Daily Times, interviewed the prisoner in his cell to learn the truth and provide his readers with a first-hand account of the accused killer’s story. However, Dempsey fed Herron a convincing string of lies and half-truths, which Herron dutifully published the next day as an inside scoop.

Dempsey lied about having an accomplice in his Anchorage killing. That accomplice, he asserted, had “doubled-crossed” him and had absconded with all the money they had taken from Marie Lavor.

He lied about his childhood, claiming that he had been abandoned by birth parents he never knew, that he had been reared by a Children’s Aid Society in White Plains, N.Y., that he had fled a farm near Syracuse and made his way at age 17 to Chicago, and that he had worked on a Montana sheep ranch for a one-legged rancher before sailing out of Seattle for Alaska.

It is difficult to say when all the lying truly began, particularly since Dempsey’s case histories contain so many contradictions. What is clear, however, is that he did not simply leave home at age 14 and work on farms for three years before returning to his parents.

According to records from the Ohio State Reformatory in Mansfield, Dempsey was working in Wooster, Ohio (in Wayne County, about 50 miles south-southwest of Cleveland), for a farmer named Wilson Clark in March 1915. One day, when the farmer was away from home, Dempsey burglarized the Clark home of money and jewelry valued at $52 and fled.

For some reason, Dempsey returned to Wooster just over a year later. He was promptly arrested on July 22 and charged with larceny. He pleaded guilty and was received, as inmate #8492, at the reformatory four days later to serve a sentence of one to seven years.

His alias at the time was Hardy Goodfellow, a name almost certainly borrowed from a young minor character in a popular 1909 biography (written by C.H. Forbes-Lindsay) entitled “Daniel Boone: Backwoodsman.” He told Mansfield authorities that, although he also sometimes used the name William Dempsey, his real name was Jack Huffman.

The pattern of lies about his background would sound familiar to law-enforcement officials over the next few years: He said he didn’t know his birth name or the identity of his birth parents, both of whom had died when he was very young. As a 6-year-old orphan, he had been taken into the home of Mr. and Mrs. Ford Huffman of Cincinnati and given the name Jack Huffman.

He lived with the Huffmans until he was 14, when he began roaming the country, working mostly for farmers. Although he knew nothing about his parentage, he seemed certain of his birthdate: Jan. 14, 1897, making him age 19 at the time of his incarceration.

The Huffmans, he said, mistreated him, and he hadn’t been home to see them in five years.

Likely, all this obfuscation was an attempt by Dempsey to shield his real parents from his misconduct or shield himself from their disapproval.

Dempsey was paroled from the reformatory on Oct. 1, 1917, and, despite a parole violation in late November, likely returned to his parents’ home in Cleveland before the end of the year.

Whether his family was happy to see him is debatable. Despite the Cleveland police report containing the parents’ claim that Dempsey led a trouble-free youth, his prison record indicates otherwise.

“Several affidavits of neighbors (in Cleveland, after his murder arrest),” said a Special Progress Report from Leavenworth prison in Kansas, “state that at various times (Dempsey) would attack others with any weapon at hand; this occurred while still a youth at home with his family. One time (he) attacked his sister with (a) bread knife, at another time beat her unmercifully, at another smashed a bicycle with (an) axe, at another stabbed four chickens with (a) bread knife.”

Alaska historian Claus-M Naske, who wrote extensively in 1986 about the William Dempsey case, described some of these actions and also implied that Dempsey’s youthful violence portended a dark future: Dempsey’s parents, wrote Naske, “said their son had suffered a serious skull fracture as a boy and experienced periods of irrational behavior, several times threatening his sister with a knife. In fact, he had acted so strangely that family friends had advised the boy’s father to commit him.”

First Murder

In custody in Seward on Sept. 4, 1919 — after being captured by members of an angry and sizable posse — William Dempsey was “tired, dirty and hungry,” having been on the run for three days with almost nothing to eat.

In an attempt to extract the truth about the two killings of which he stood accused, authorities denied him what he wanted most: comfort, sleep, food and water. According to U.S. Deputy Marshal Frank Hoffman, Dempsey was made to stand for several hours and denied all forms of nutrition while he was interrogated.

After confessing fully to both crimes, wrote one newspaper, Dempsey “was a nervous wreck and dropped to the floor in a dead faint. Medical attention was necessary to revive him.”

U.S. Commissioner William H. Whittlesey remanded Dempsey to the custody of U.S. Marshal Frank R. Brenneman, who was tasked with transporting the prisoner to Valdez, seat of the Third Judicial District, where he would appear before a grand jury. In both Seward and Valdez, he was held without bail.

Despite the clarity of his confession — “I did the deed by myself,” he reportedly averred — Dempsey would later alter his story of Lavor’s death, in the courtroom and again in a series of letters to the man who had been the judge at his trial, Charles Bunnell.