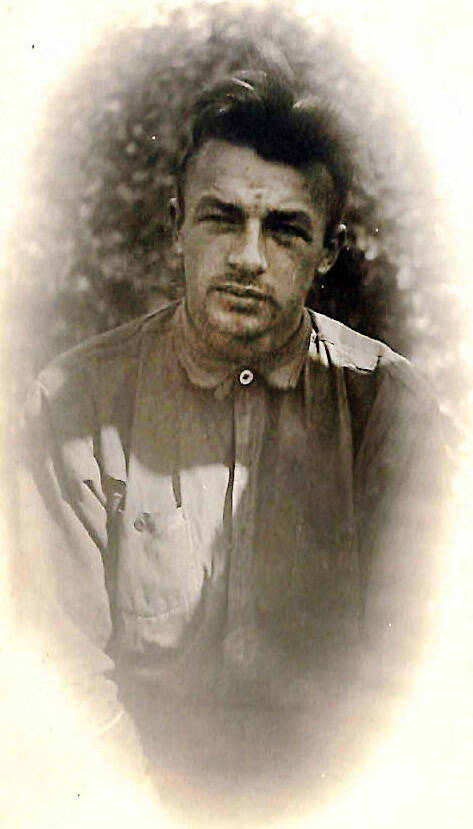

AUTHOR’S NOTE: William Dempsey killed two Alaskans in 1919, was sent to prison in 1920 for his crimes, and escaped from prison in 1940. The first seven parts of this story introduced Dempsey’s victims and the judge who presided at his trials. Dempsey spent more than a decade attempting to persuade that judge, via letters from prison, to recommend him for executive clemency.

Three Women

According to the American Psychological Association, hybristophilia is a sexual interest in or strong attraction to those who commit crimes. Generally speaking, hybristophiliacs are women who seek the companionship of or an acknowledgement from men convicted of violent offenses.

In practice, the sexual attraction may be sublimated to other impulses, such as a desire to change the violent individual and divert him from his sociopathic or psychopathic ways. Some women, for instance, see the “little boy” a killer once was and seek to nurture that “inner child.”

Such infatuation has led to some women marrying men who are incarcerated, or even to fathering children with such men. The serial killer Ted Bundy attracted numerous women to his trials. Likewise, women have clamored for the attention of killers such as Charles Manson and Richard Ramirez, among others.

The imprisoned men may receive visits from these women or may become, in essence, pen pals with them. The more manipulative inmates may use the desires of these “prison groupies” to foster character witnesses for their defense, to generate repeals of their convictions, or even to advocate for some prison privileges or their eventual release.

It is likely that some form of hybristophilia is what brought three women into the fold of the imprisoned William Dempsey and prompted them to begin letter-writing campaigns to urge former judge Charles Bunnell to aid Dempsey, despite Dempsey’s incarceration for murdering two Alaskans in 1919.

The earliest letter appears to have been written in June 1928 by a Chicago woman named Gertrude W. Webster, who said she knew Dempsey’s family well and wanted only to ask Bunnell if he would consider recommending Dempsey (whom she felt sure had learned his lesson) for a position as prison trusty. Bunnell wrote back promptly and declined Webster’s request.

The second woman to write Bunnell on Dempsey’s behalf was Louise Lynch of Torrance, Calif., in January 1932. Her initial letter demonstrated several gross misunderstandings of the facts and expressed her belief that Dempsey was in prison for a crime “he never committed.”

In a later letter, Lynch admitted that most of her information about Dempsey’s trials had come from Dempsey himself, as they had been writing back and forth for some time. “I can’t understand him making up such statements if they were not true,” she informed Bunnell.

In that first letter, Lynch also claimed that Dempsey’s sister, Mary, had written to her only a week earlier to say that their mother was “at death’s door” and was crying out for her son—and so on and so forth, each new theme an echo of those already proffered many times by Dempsey himself.

In January 1934, a third woman joined the chorus urging forgiveness and understanding. This time it was Flerine Barnard of Whittier, Calif., who identified herself as “a friend of (William) and family for years.”

Dempsey’s mother, Barnard informed Bunnell, had died. (This was true.) His father was old. One of his sisters was a widow and was destitute. Barnard claimed that Dempsey had a well-paying laboratory job awaiting him in California once he was released, and that such employment would allow him to send life-saving funds to his ailing family in Cleveland.

Of Dempsey’s character, she wrote: “(William) is not a criminal and (is) from a family of blood and breeding…. William’s mother died of a broken heart, and God grant that he is released before his father passes on that he may be some comfort to him in his old days.”

Always polite but also ever skeptical, Bunnell wrote to ask Barnard to clarify how she knew William Dempsey’s family. Although Barnard later claimed that she had known Dempsey since he was a child, she seemed to notice no contradiction when she admitted to Bunnell that she had lived most of her life in Texas and Oklahoma before moving to California 10 years earlier.

Despite these geographical differences, she provided Bunnell with numerous “insights” into Dempsey’s childhood: “His mother and I often discussed him and had great hopes for his future. His parents were preparing to have him enter a medical or law college when he had graduated from public school and also have him attend an academy of music to study violin, for his father was recognized as one of the leading musicians in that vicinity of Cleveland.”

Barnard referred to Dempsey as “a model child,” with “exceptionally good” conduct and the praise of his teachers for the earnestness he expressed in seeking an education. “He was well liked by all,” she wrote, followed by the usual litany of excuses and rationalizations for Dempsey’s missteps.

Bunnell’s primary response to these women continued to be: (1) Dempsey was fortunate to have escaped execution. (2) If he really took the fall for others in the Lavor case, he must reveal their identities. (3) We have witnesses to prove that he absolutely was guilty of killing Marshal Evans.

None of these women, despite their claims of familiarity with Dempsey’s family, seemed to know that Demski, not Dempsey, was the family’s actual surname. None of them ever provided any indication that the others were also corresponding with Dempsey and were spouting the same arguments and falsehoods he dished out over the years.

Postscripts

Over the years, Dempsey continued to dangle in front of Bunnell the bait of the “truth” about the Lavor killing, and Bunnell continued to urge him to provide evidence. But even Dempsey must have tired of this cat-and-mouse game, realizing that he would have to either put up or shut up. So he adjusted his approach.

He said the men who truly killed Lavor were now productive members of society back in Anchorage. If he ratted them out, he would be destroying their lives and the lives of their innocent families. Informing on them now, he added, would make him a modern-day Judas Iscariot. Even Bunnell had to appreciate his loyalty, argued Dempsey.

Dempsey also smirkingly explained that he knew—even if Bunnell failed to understand—why his death sentences had been commuted to life in prison: “Evidently you do not know yet that President Wilson was a man strictly against Capital Punishment, & during his whole tenure of office never affirmed a death sentence … but evidently he felt you were not entitled to know.

“Have you ever read President Wilson’s autobiography?” he continued. “If not, do so, & you will learn much about him [and] why he was one of the Greatest & most worshipped Presidents this nation ever had.”

In an April 1934 letter to Bunnell, though, Dempsey’s veneer of civility cracked, as he concluded with this remark: “Will you want to be judged by God as you are Judging me? If so, then the lowest pit of Hell will be too good for you.” Three lines later, he again asked Bunnell to consider him for executive clemency.

After a two-year gap in their correspondence, Dempsey wrote to Bunnell one final time in a letter dated Aug. 29, 1936. Dempsey’s arguments were essentially the same: He had been unjustly incarcerated. Because he lacked money and power, he must beg for succor. And his family, especially his aged father, really needed him.

He concluded: “So for their sake more than mine, I beg you to recommend Executive Clemency.”