AUTHOR’S NOTE: Solving the mystery of Shackleford Creek and the former Shackleford cabin in Cooper Landing led first to a young Rhode Island miner named Fred Shackleford, then to a California entrepreneur named Richard M. Shackelford. The spellings were different, and errors were made, but eventually the truth came out — with a few twists along the way.

The front page of the Los Angeles Herald on Feb. 10, 1901, featured a multi-deck headline that began with these three words in all caps: “SHACKELFORD IS BANKRUPT.”

The bad year was just beginning for Richard M. Shackelford, a highly regarded California entrepreneur. While he had assets valued at more than $84,000 (about $2.1 million in today’s money), his debts were more than double that amount. His Alaska Hydraulic Syndicate mining operation on lower Kenai Lake was failing to produce as he and fellow investors had hoped. And exactly one year after the bankruptcy notice, his wife, Mary Louise, died in a San Francisco hospital after a prolonged illness.

But Shackelford would rise from the ashes of these misfortunes. He would regain financial solvency. He would help establish the California Polytechnic School. He would remarry. And when he died on Jan. 12, 1915, just five days shy of his 81st birthday, he would be revered as one of the leading men of San Luis Obispo County.

Back in 1898, three years before the bankruptcy bombshell, Shackelford had sailed to Alaska to personally see to the establishment of the mine on the creek that would one day bear his name — unfortunately misspelled.

According to Mary J. Barry’s “A History of Mining on the Kenai Peninsula, Alaska,” Shackelford and his mining crew landed in Resurrection Bay on March 27 or 28. However, according to the April 16 Seattle Post-Intelligencer, Shackelford didn’t leave the Lower 48 until the following month. Instead, the newspaper reported, he and a 16-man prospecting team were passengers on the steamer Excelsior when it departed Seattle on April 15, bound for Cook Inlet.

After arriving in Resurrection Bay — and needing a place to store their sawmill and large pieces of hydraulic mining equipment so they could survey good prospects on the upper Kenai River — they erected a house from the California redwood lumber they had transported north. Then Shackelford and crew headed up the wilderness trail away from the bay and toward Kenai Lake.

By this time, April had lapsed into May, and the Shackelford group moved up the trail slowly enough to be caught on May 31 by Walter C. Mendenhall and his two-person U.S. Geological Survey crew.

Mendenhall noted the encounter in his final reconnaissance report for the federal government, and misspelled Shackelford’s surname in the process. The error was perpetuated throughout the succeeding decades.

By 2002, when the U.S. Forest Service discussed mining history during an analysis of the Cooper Creek watershed, Mendenhall’s error had become established fact: “During the early part of this period, Resurrection Bay near Seward was the primary starting point for miners coming to Cooper Landing. In the spring, miners used horses to pull sleds with their gear and food from Seward to the south end of Kenai Lake. Crossing the lake ice in the spring was treacherous, with horses and men falling through on occasion. These travelers cached most of their gear along Kenai Lake at Shackleford Mine (one mile east of the lake’s outlet) and boated down Kenai River to Cooper Creek with heavy loads.”

According to several biographical sketches written about him, Richard Shackelford had long been enchanted by the notion of gold mining. In fact, the Kentucky native first came west as a teenager in 1853 to join in the California gold rush. After a spate of mildly productive years spent as a miner while completing his education, he tucked away his golden dreams and diversified.

By the late 1890s, he had shares in a flour company, a fruit farmers association, at least two lumber companies, the Southern Pacific Milling Company, and much, much more — eventually including the Alaska Hydraulic Syndicate.

Shackelford also spent more than 30 years as a school board member, was active in several fraternal organizations, owned large tracts of land, voted Republican, and was a founding member of the Methodist Church he attended in his home town of Paso Robles.

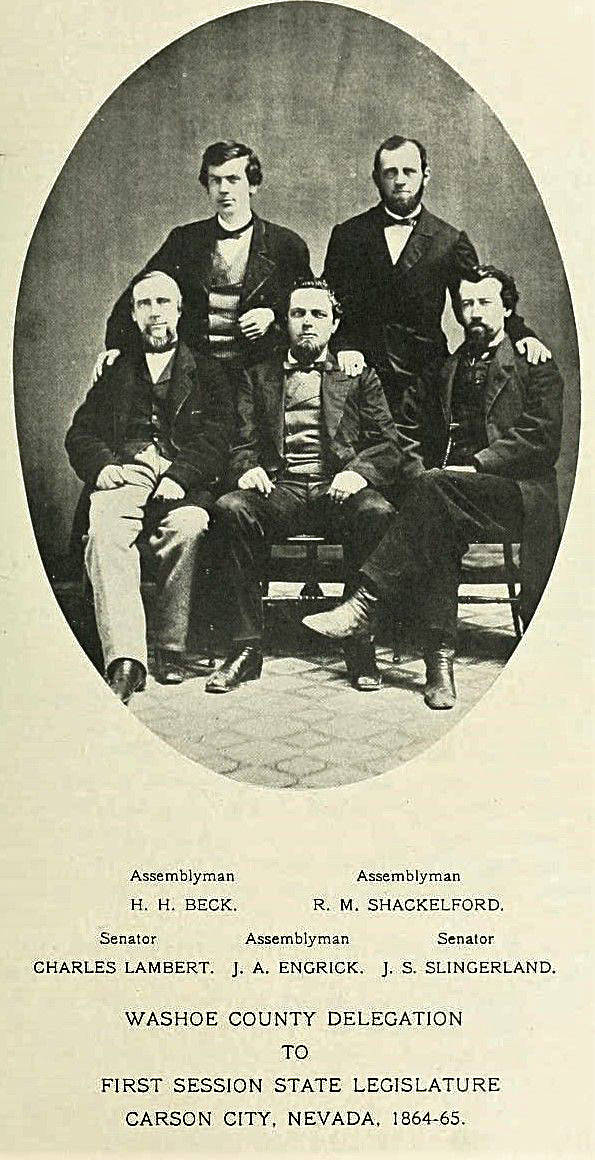

More than anything, Shackelford was an opportunist. Back in the early 1860s, while hauling freight between California and Virginia City, Nevada, he was asked to run for office in Nevada. He was elected to the first Assembly of the new state and served for two years before returning to California.

Prospecting for gold in Alaska was likely another opportunity Shackelford simply couldn’t pass up.

According to Mary Barry, Shackelford, then in his mid-60s, remained in Alaska for two years, but Shackelford’s hometown paper appears to dispute this: On Aug. 27, 1898, the Paso Robles Record reported, “R.M. Shackelford has returned from Alaska and is expected in Paso Robles this evening.” If he ventured again to Alaska, I could find no record of it.

If, however, Barry is correct, Shackelford must have returned to Alaska and then sailed home again around 1900 to tend to family and business interests.

Mining on Shackleford Creek had likely ceased by 1905. At some point, any equipment that remained and the cabin named after Shackelford were sold, according to Barry.

The final fate of the cabin may be lost to history. The cabin could have been dismantled. It could have been washed away in a flood or burned in a forest fire or some woodstove mishap. It could have simply disintegrated over time and merged with the soil on the Kenai Lake shoreline.

But in 1910 — the same year the cabin was noted on Dr. David H. Sleem’s map of the Kenai Mining District—it received attention in the press.

That fall, Howard B. Smith, a wealthy Connecticut pharmacist and avid hunter, hired guide William Weaver and packer Alfred Lowell to take him into the Kenai Mountain after trophy game. Returning with “two fine moose heads” to Cooper Landing by dory on Oct. 11, the trio hit heavy seas on Kenai Lake and capsized about 150 yards offshore. Only Weaver could swim, and only he survived.

Once he reached shore, he said later, “I then departed for Shackleford’s cabin, which I knew to be occupied, to seek assistance. I found the Lean brothers and Martin there, and they returned to the scene of the disaster with me.” Smith’s body was later recovered, while Lowell’s was never found.

The story, complete with the misspelled Shackleford name, made it into the Seward Weekly Gateway on Oct. 15, 1910, and later made national news because of Smith’s high status out East.

When Donald J. Orth published his extensively researched, 1,100-page Dictionary of Alaska Place Names in 1971, he listed “Shackleford Creek” and said it was a “local name reported in 1952 by USGS.” However, the creek, complete with its misspelled name, appeared in print at least as early as October 1908, when the Seward Weekly Gateway published a brief mentioning that “moose hunters near Shackleford Creek had to follow the moose up into the hills to get any.”

The misspelling of Richard Shackelford’s surname, first published incorrectly in 1900, has continued throughout history — despite Shackelford’s own notoriety in California — and has blurred the origins of the creek name for more than a century.

Read Part One and Part Two of the Shackelford saga.

• By Clark Fair, For the Peninsula Clarion