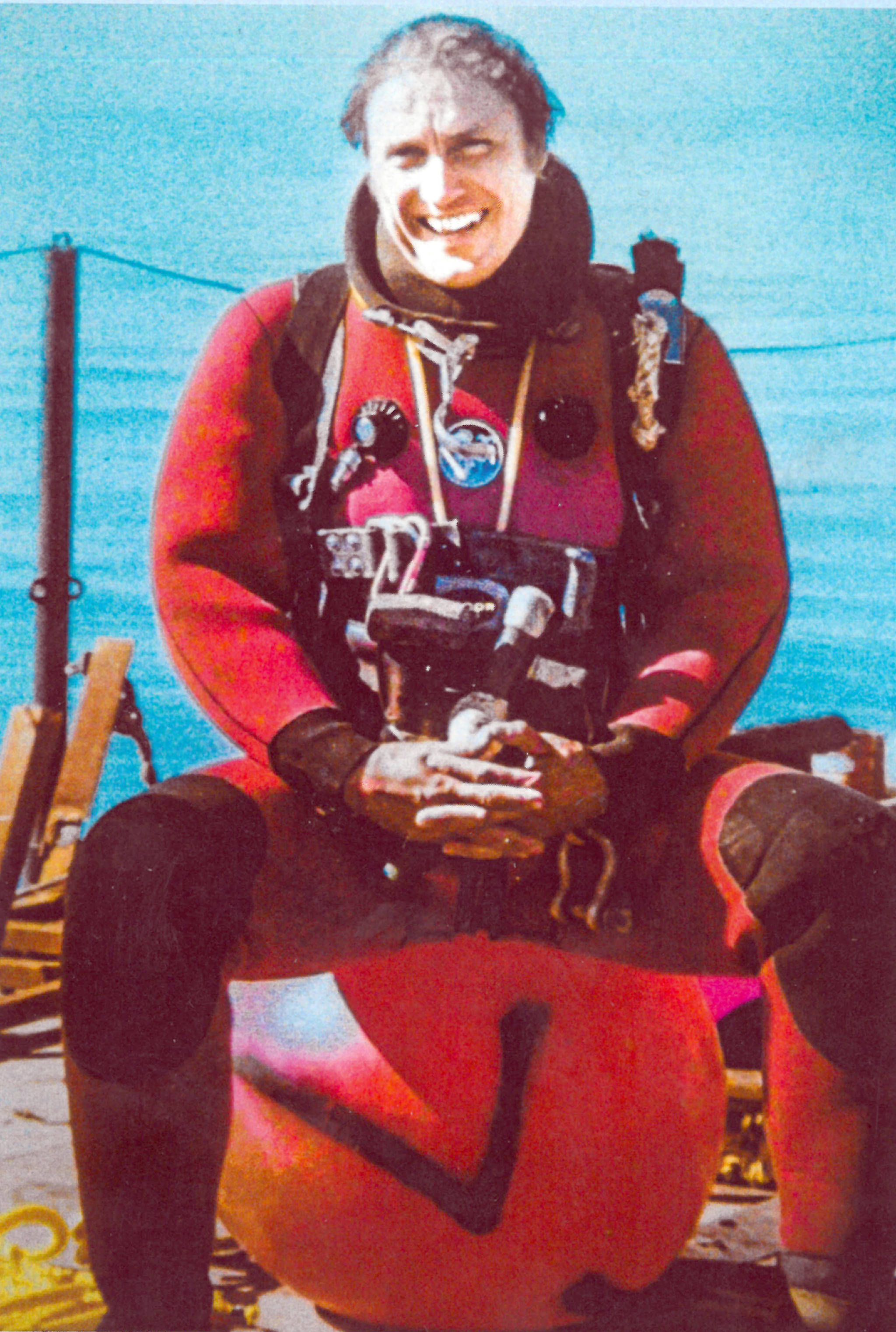

Owen Boyle spent 40 years diving the dangerous waters of Cook Inlet, submerging himself in the treacherous tides and blinded by the dark waters, to work as a commercial diver.

Boyle, who lives in Nikiski with his wife Fleur, began his career in Cook Inlet in 1965 when he flew from Anchorage to a derrick barge anchored next to the Baker Platform in the North Middle Ground Shoal field, just northwest of Nikiski.

“In the early days, they were desperate to get those platforms in,” Boyle said.

This first dive began a career that has been nationally recognized by the Association of Diving Contractors International (ADCI), which inducted Boyle into the Commercial Diving Hall of Fame this February. The full scope of Boyle’s career is also detailed in his memoir “Diving Blind into Danger.”

“Behind his nomination, is the fact that he showed an ardent persistence in addressing a real challenge that faces the divers (in the Cook Inlet),” said Phil Newsum, executive director of ADCI.

Boyle began diving when he was 10 years old and describes it as a natural thing for him.

When construction on the oil platforms in Cook Inlet began to take off, Boyle jumped at the opportunity to travel to Alaska. He was qualified to work on the platforms, after spending several years training and working in California. But, according to Boyle, years of experience couldn’t prepare him for the exact complications that come with diving the Cook Inlet.

“My first dive in the inlet, it’s something that I’ll never forget,” Boyle said. “I had quite a lot of experience with diving, but the upper inlet is totally black. You leave the surface and you’re blind. And the tides, they are ferocious. I had dived in black water and fast water before, but never at the same time.”

In his book, Boyle recounted the advice he received from Gene Cleary, his dive partner, just before he put on his helmet for the first dive.

“We always start diving when the tide is still running,” Cleary said. “This gives you early current directions, either ebbing or flooding … but that doesn’t last too long. If you’re lucky, the tide may go completely slack, but that doesn’t happen too often. Sometimes it never stops.”

The tides in Cook Inlet are extreme, the most extreme in the United States according to the National Ocean Service, with a range in tide of 35 feet.

“The low tide, when it’s coming down it will come at six knots or more, and so will the high tide when it’s going back the other way,” Boyle said.

Divers have to get in the water at the low tide and complete their jobs within a 25-minute window before the tide shifts.

“It never stops,” Boyle said. “The tide is coming down and it’ll slow down enough so you can dive. Then it will start going southwest to the west and off it will go and then it starts coming back in. You have to get out of that tide when it starts going west, or it will trap you down there with your hose against all the braces of the platform.”

While in these tides, Boyle would be completely blinded by the dark depths of Cook Inlet. Going off of touch, memory and with the help of his tender, a person above water that can communicate with a diver through their hose, Boyle would work as fast and well as he could before the tide shifted.

He would tighten bolts, place sandbags under pipes and spool up — which is when two pipelines have been laid and are ready to be connected to the correct tube on each of two legs. He completed these tasks with the tools he would bring down with him and a mental picture of blueprints in his head, while navigating himself and his hoses around the platform’s braces in the pitch black dark waters.

“He is considered to be the father of being able to address the challenges with diving in the Cook Inlet,” Newsum said. “He is recognized by his peers in the industry as someone that did that hard work with a lot of intuitiveness and courage.”

According to Boyle, the most dangerous thing a commercial diver does is ‘burning,’ when a diver uses an underwater cutting torch to cut a thick steel plate in half.

“Even in clear water, burning is a difficult skill and Inlet divers must do it in zero visibility water,” Boyle said. “… It’s not the risk of a torch explosion. It’s the risk of the big heavy object you’ve just cut loose breaking the restraining rigging and lashing back at you.”

Throughout the 40-year span of his career, Boyle worked on platforms throughout Cook Inlet, facing the “unknown dangers awaiting the divers on a new and unexplored platform,” he said. He has adventurous stories from the Baker, Dolly Varden, Steelhead and Osprey platforms and the dangerous jobs he completed at each.

His book is full of tales of rescues and bar fights, of underwater hallucinations and divers suffering from the ‘bends,’ of incompetent captains and near-death experiences.

“I think the greatest thing about Owen is his willingness to go out of the way to mentor others, to pass on that knowledge, his stories and those techniques to subsequent generations of divers who have him to look up to,” Newsum said.

Boyle quit diving around 2004, but stayed in the trade as a supervisor, teaching the next generation of Cook Inlet divers how to dive blind, until 2007, he said.

At the age of 75, he took his last dive in Cook Inlet. He is now 85-years-old, and has replaced diving with writing to continue passing on his knowledge.

“I wrote the book about it, quite a few adventures in there,” he said. “It’s very dangerous diving.”

Kat Sorensen can be reached at kat.sorensen@peninsulaclarion.com.