By Clark Fair

For the Peninsula Clarion

AUTHOR’S NOTE: This is the seventh and final installment in a series about two killings that occurred in Kenai on April 8, 1918. Parts One through Four introduced three manipulative men — Alexander “Paddy” Ryan, William “Bible Bill” Dawson and Cleveland Magill — and demonstrated how the three men wove themselves into the fabric of Kenai and into conflict with each other. Parts Five and Six introduced a fourth man, Charles Coach, a Cook Inlet trapper, and described how, on that fateful April day, Coach killed Magill, who had earlier killed Ryan.

AFTERMATH AND LEGACY

When the City of Kenai celebrated its bicentennial in 1991, the city council and the mayor, seeking ways to honor city pioneers, had a plaque created and erected near the small creek flowing through the gully behind and below the Kenai Senior Citizen Center.

The creek had been known for many decades as Ryan’s Creek, and the new plaque memorialized Alexander Ryan, the former mail carrier and U.S. special deputy marshal who had once lived on the hill above the creek.

Also in 1991, when journalist Tom Kizzia crafted a multi-part series focused on the Native people of Kenai, he suggested that the city government may have been under the false impression that Ryan — who left behind an estate valued at $388.85 — had been a “beloved community leader, gunned down while trying to exercise his American right to vote.”

Recently, Robert Frates, the city’s director of parks and recreation, said he was unaware of any plaque connected to the city’s Ryan’s Creek Trail. It is possible that, as Ryan’s history became better understood, the plaque was removed.

Shortly after the 1918 shootings, the bodies of both Alexander Ryan and Cleveland Magill were buried in the Kenai cemetery. No record of Ryan’s burial appears in the Totem Tracers’ book, “Cemetery Inscriptions and Area Memorials in Alaska’s Kenai Peninsula Borough.”

Magill’s body, on the other hand, was exhumed on April 21 by Anchorage mortician Daniel H. Williams under the orders of Judge Leopold David, as requested by Magill’s family back in Washington.

After being stuck in Kenai for 11 days by bad weather, Williams caught a power boat to Anchorage and on May 9 sent the body — along with a letter explaining what he had learned about Magill’s death — on an Alaska Steamship Company vessel bound for Seattle.

It was Williams’s letter upon which the pro-Magill story of the shooting was based when it was published near Magill’s hometown. Included in the letter were references to Kenai’s criminal element, particularly its bootleggers, plus a few terse words from Judge David.

The judge claimed that Ryan had been well known as “a bad character.” Charles Coach, he said, had taken it upon himself to impersonate an officer and “had no right” to shoot Magill. “I believe,” the judge concluded, “the principal reason Magill came to his death was that he fearlessly enforced the law.”

Magill’s second funeral occurred May 22 in Dayton.

His estate, which was settled in probate court in November 1923, indicated that he left behind personal belongings (including more weapons) and about $700 in a Juneau bank. Claims against his estate amounted to more than $1,100.

One day before Magill’s second funeral, The Alaska Daily Empire (a Juneau paper) — almost certainly spoon-fed details by pro-Ryan witnesses on hand for Coach’s grand jury trial in Valdez — took a tack opposite Judge David’s.

“From all accounts,” the paper wrote, “Magill was considered ‘a bad man,’ a brutal bully and a notorious gun-man. Since being appointed Commissioner he practically ran the town.”

Included were lurid details of his allegedly brutish behavior, especially against women.

About the same time Magill was being reinterred, Charles Coach received his expected exoneration. The grand jury returned “no true bill,” meaning that any charges against Coach were dismissed for lack of evidence.

A few days later, the Seward Gateway reported, Coach was on his way back to Kenai on the steamship Alameda, the same ship he would take to the Lower 48 in September for a vacation.

On Oct. 25, more than six months after the shootings, a small “society” item appeared in a small town Colorado newspaper to say that Coach had been visiting in the area and was now heading home to Seldovia.

In his series on early Kenai, Kizzia reported that the body of Charles Coach was found in the spring of 1919 on the west side of Cook Inlet, where he had had a trapline. It was believed, wrote Kizzia, that Coach had used his own shotgun to commit suicide.

Whether the identity of the suicide victim or the year of his death was correct, or whether the suicide ever happened at all, one thing is certain: Charles Coach lived at least six years beyond the shootings in Kenai.

He appeared in the 1920 U.S. Census for “Tuska” (Tutka) Bay on the shoreline of “Ketchinask” (Kachemak) Bay, listed as a 39-year-old trapper and a 1909 immigrant from Austria.

He appeared in 1923 in a small Associated Press wire story that circulated throughout the United States. Cook Inlet resident Charles Coach, it said, believed that inter-racial marriage was spelling the demise of the full-blooded Alaska Native.

And he appeared in 1924 — again in an AP-wire story in newspapers across the country — this time as Cook Inlet seal hunter Charles Coach, an expert observer of how seal mothers teach their pups to swim.

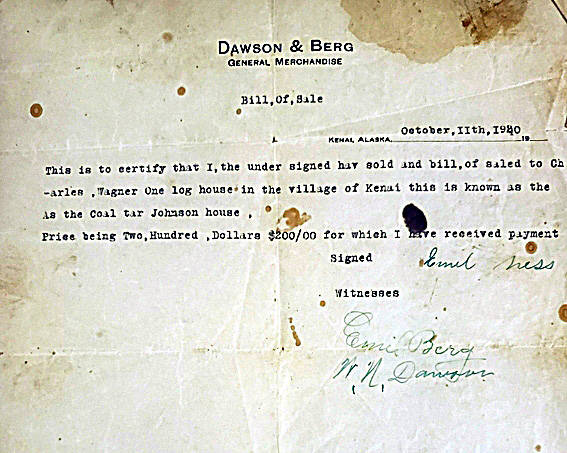

In 1920, 74-year-old William Dawson — of whom the Dolan sisters once wrote, “The lines on his face were myriad, etched there by time and wickedness” — was still running a store in Kenai, but with a new business partner, big-game guide Emil Berg. Their store became Dawson & Berg General Merchandise.

In November, Dawson and Berg nearly perished when — carrying just three days of provisions — they encountered a storm when they decided to motor to Anchorage to resupply their store.

As their small skiff ran low on fuel they were forced to run ashore near Point Possession and attempt the long walk home. They were rescued more than a week later, exhausted from over-exertion and exposure. Berg, then in his early 40s, had fallen and broken an arm.

Two years later, Dawson, battling kidney disease, spent five days in a government hospital in Anchorage before succumbing on Oct. 30, 1922. He was buried a few days later in the Anchorage Memorial Park Cemetery.

On Nov. 22, Anchorage mortician Daniel Williams — the same man who had exhumed and shipped the body of Cleveland Magill to Washington — typed a formal note on his own letterhead to Lester Ischmael Mitchell of Craig, Missouri, to discuss Dawson’s sizable estate.

Mitchell was the son of Dawson’s youngest sister, Nancy — almost 17 years his junior and the sole-surviving member of Dawson’s immediate family. Williams estimated the value of Dawson’s estate at between $100,000 and $150,000, mostly in the form of store merchandise and real estate.

Four year earlier, under orders of newly elected Alaska Territorial Gov. Thomas Riggs Jr., the ballots from the school board election of April 8, 1918, had been discarded. A new election had been held.

One day after the shootings, Nelson Steele, one of the teachers that Cleve Magill had scrambled to hire after his other two instructors resigned in mid-school year, was appointed interim principal of the Kenai School and instructed to take over Magill’s classes for the remainder of the term.

Later, Steele also assumed Magill’s duties as U.S. Commissioner in Kenai. Few people seemed to miss the previous holder of the job or the man he had shot and killed.

In their teaching memoir, the Dolan sisters, who had left Kenai in 1914, said they had learned of the shootings when a young Native man, one of their former Kenai students who had been drafted into the military, looked them up and told them the story.

“There had been always a feud by one faction headed by or instigated by ‘Old Bible Bill,’” they wrote, “and another by the better element of the place. Perhaps these killings brought the feud to an end.”