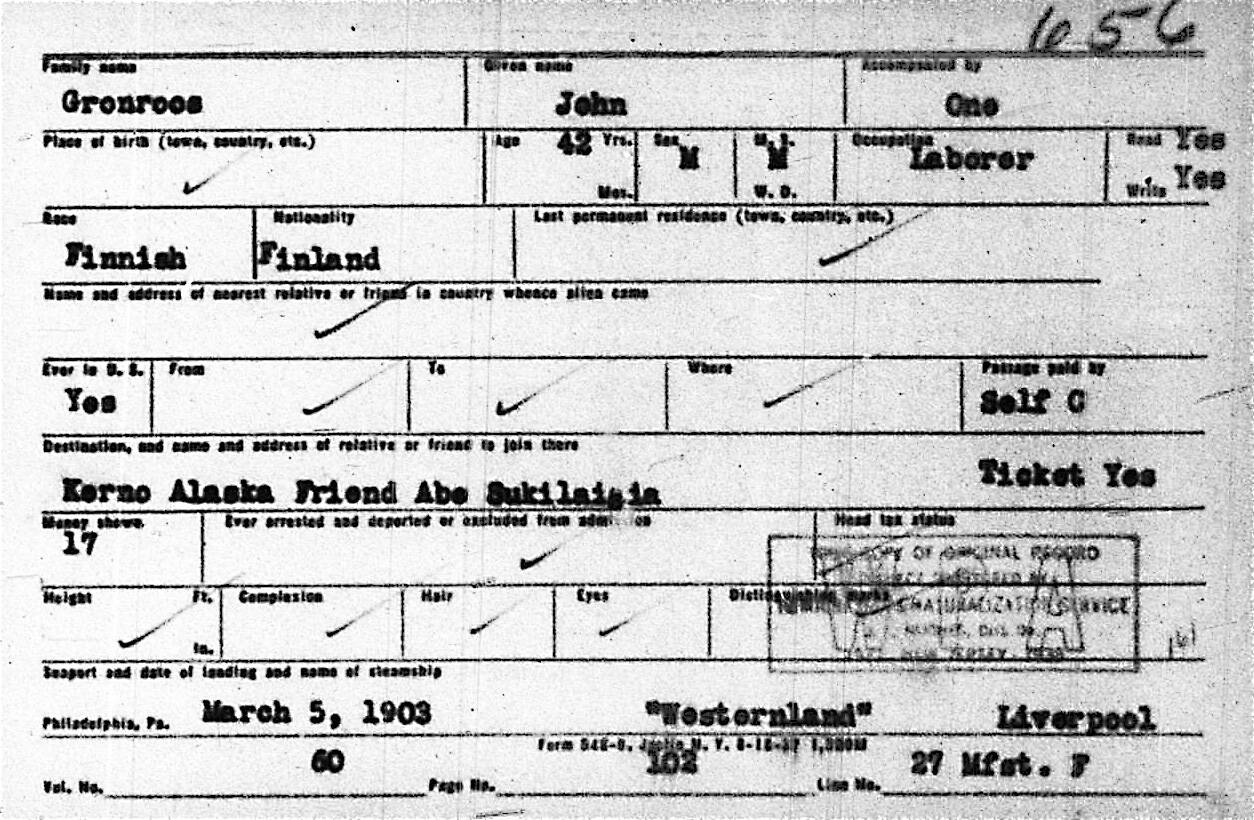

AUTHOR’S NOTE: The five-member Grönroos family immigrated from Finland to Alaska in 1903 and 1904 and settled just north of the Anchor River mouth. Before and after the family matriarch, Sophia, escaped drowning in 1914 when the ship on which she was sailing home sank in Puget Sound, the Grönrooses faced numerous other challenges.

Life’s Trials

The source of the conflict was not stated, but the Seward Daily Gateway, in mid-October 1913, reported that John Grönroos was about to be arrested. Alyce E. Anderson, a government schoolteacher in Ninilchik, told the newspaper that Grönroos, an Anchor Point homesteader, had fired two shots from either a rifle or a revolver at one of his neighbors, a man named Jacob Petaja.

Petaja, said the paper, was expected to travel to Kenai—once the area’s inclement weather subsided—and to file a complaint against Grönroos so that an arrest warrant could be issued. Given the proximity—and possible overlap—of the Grönroos and Petaja lands, just north of the Anchor River mouth, it seems likely that the dispute centered on property boundaries.

But if Petaja ever did file a complaint, that action may have failed to result in an arrest. In fact, by the middle of the following month, the conflict had been rendered moot.

On Dec. 1, George Brown, the winter mail carrier, arrived in Seward and announced that on Nov. 12 the Grönroos patriarch had been killed instantly near his home when several large fish-trap pilings had rolled over him. He was 52 years old.

Since Grönroos’s daughter (Aino) had previously moved out of state, only his wife (Sophia) and their two sons (Johan and Laure, commonly called John and Larry) remained at their Anchor Point home. Because none of these Finnish immigrants had been naturalized, they owned their two-story log house but had no legal right to the land on which it stood.

By 1920, the Grönroos trio remained intact and its status unchanged. But by the time of the 1930 U.S. Census—actually enumerated in Anchor Point on Nov. 6, 1929—Laure had become a citizen and had the right to gain title to property. Seventy-year-old Sophia, however, as owner of the Grönroos house and as de facto head of the family, was still not naturalized and had no right to own the land on which she and her two bachelor sons lived.

Sophia left home rarely during this time. In fact, the Seldovia Herald noted that her visit to Seldovia in the summer of 1930 was her first in two years. She made the paper again two years later when she visited to spend the Fourth of July in town.

The Herald complimented Sophia Grönroos on the size and quality of her garden in Anchor Point, her 28-year tenure on the Kenai Peninsula, her many friends, her active interest in public affairs, and her dog that apparently was adept at helping her with chores, including dragging sacks of coal up from the beach.

But events in the next few years led Sophia to think about leaving Anchor Point—and Alaska—for good.

In 1932, her two only grandchildren were married—granddaughter Florence in Seattle and grandson Howard in Los Angeles. In March 1937, her younger son, 46-year-old Laure, died. Only her elder son, John, remained with her on the homestead, and his presence was apparently not enough to keep her in Alaska.

In 1938, she moved to Everett, Washington, to live with her daughter. She died there on March 1, 1941, at the age of 81. Although she had lived in the United States for 37 years, she had never surrendered her Finnish citizenship in order to legally become an American.

Back in Anchor Point in 1939, John was the lone remaining Grönroos. With full ownership of the house that he and his father had built in 1903, and now its sole decision-maker, he filed for a patent to the land—two parcels, 53.95 and 40 acres, respectively. But it may have been an empty gesture. He, like his mother, had never been naturalized and could not gain title to property.

The 1940 U.S. Census referred to Johan Vaino Grönroos as “John Granroos.” He was listed as a commercial salmon fisherman and an alien. Two years later, in Kenai, he signed a draft-registration card, stating that he was working for the Libby, McNeil & Libby cannery but receiving his mail via Homer. He was listed as 5-foot-8 and 180 pounds, with blue eyes, gray hair and a ruddy complexion. He was 58 years old.

In Washington, his sister Aino, in her late 40s, was finally preparing for naturalization. Her children were married, and she and husband Gustaf were empty-nesters. She filed the initial paperwork for citizenship in 1943.

Aino would outlive John by several decades. When she died in Bothell, Washington in 1991, she was 98 years old and had also outlived her husband and both of her children.

The Newcomers

By May 1947, Larry and Inez Clendenen had made the move to the Kenai Peninsula. With their two children, they were living in a cabin a quarter-mile off the main street in Homer, while keeping their eyes peeled for available homestead land.

With a trio of other property seekers, Larry Clendenen explored east of Homer, checking out the Fox River country at the upper end of Kachemak Bay, but he didn’t see any land that called to him. He and the others headed north.

“We found a homestead in June, at Anchor Point,” wrote Inez Clendenen in the “Family Stories” section of “In Those Days: Alaska Pioneers of the Lower Kenai Peninsula.” “We flew out and landed on the beach. Walked up the hill where there was a big hand-hewn log house. The place had been filed on in 1903 … by the Granroos [sic] family. They had lived on the property but had never proved up on it…. When the last one who had originally filed on the property died, there was a daughter … living in Washington. We got in touch with her and were able to buy the improvements.”

That “last one” was John Grönroos, who had died one year earlier. According to Vi Chapman in the Anchor Point chapter of the 1983 book “A Larger History of the Kenai Peninsula,” Grönroos “was lost when he went in his small skiff down the inlet to visit a friend.”

On Sept. 20, 1946, the Probate Court for the Territory of Alaska appointed John Paul Standke, another Grönroos neighbor, to be administrator of the John Grönroos estate. Standke arranged for the proper legal notices to be published in Southcentral Alaska newspapers and wrapped up his administrative duties by the middle of 1947.

The Clendenens, meanwhile, contacted Aino (Grönroos) Hill in Everett, Washington, and arranged to purchase the house, its contents, and any outbuildings or other features created by the Grönroos family. They filed on the homestead on June 2, 1947, the same day on which John Grönroos’s claim was officially relinquished, and they received patent to the land on Oct. 17, 1949.

“The house was very warm,” wrote Inez. “There was food, furniture, bedding and (ship-building and other) tools, so were set up very well.” The Clendenens moved in and made themselves at home.

And they discovered a few surprises: “We learned that our new home had once been a trading post for fishermen, trappers and anyone stopping by,” said Inez Clendenen. “We (also) found several stills on the place, where they made whiskey to sell. We heard they would make trips to Seldovia, where they could trade their whiskey for goods.”

In 1948, the year in which Larry’s Clendenen’s cousin, Lorna Keeler, and her family settled in Anchor Point, the Clendenens’ new home burned to the ground, the fire taking with it most of the final traces of the Grönroos presence. Larry and Inez built a new home for themselves, and a new life, near the site where a quintet of other new starts had begun more than 40 years before.