When Beverly Christensen died at age 87, she was buried in Spruce Grove Memorial Park in Kasilof. The burial was 25 years ago, marking the longest period of time that she has remained in one place.

Given that Christensen spent most of her final decades in long, peaceful stints in Cohoe and Clam Gulch, some may find it surprising to learn that the first half of her life was tumultuous and filled with almost constant movement and upheaval.

Before she was 15, Christensen — born Nora Beverly Cox on Sept. 21, 1907 — had moved nearly every year, sometimes more than once a year, and her father, a younger brother and her younger sister were all dead.

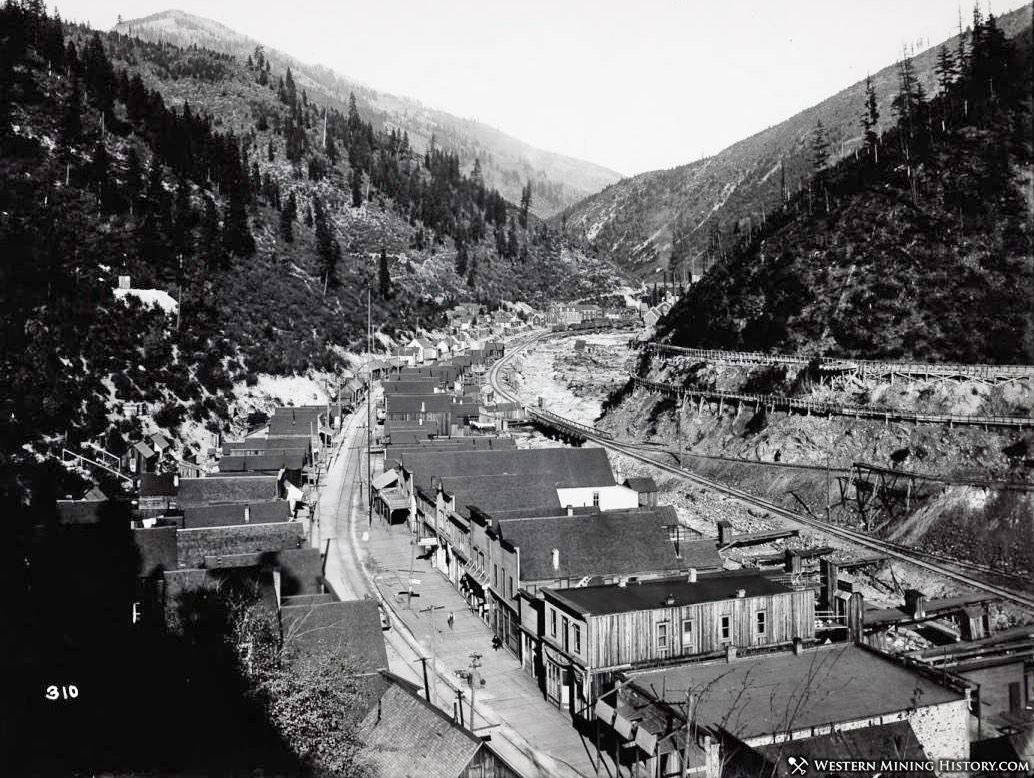

Christensen’s father, Charles Sumner Cox, was a hard-rock miner, and the family, including Charles’s wife Gertrude and their son Ted, was living in remote Gem, Idaho, when Beverly was born. Gertrude had been a public-school teacher before marrying Charles in 1904 and starting to produce offspring. By 1912, she would have five children, and her family would have moved again and again as Charles shifted to the Alhambra mine and the Corrigan mine, and so forth, wherever he could find another job.

Life for itinerant miners and for the small mining towns they inhabited was, at best, ephemeral. Accidents happened. Disagreements erupted. Ore lodes played out. Mines closed. Jobs began quickly and ended just as quickly. Gem, Idaho, is now a ghost town on Canyon Creek, north of Wallace.

In a personal history videotaped late in her life, Christensen said that when she was about 3, the family was living in Government Gulch, Idaho, and she recalled walking to the mine with her older brother Ted to deliver lunch to their father.

Two years later, in 1912, the Coxes were living in Wardner, Idaho. Two years after that, Beverly’s two-year-old sister Marion died, possibly of cholera.

In 1916, Charles was listed as a miner in Kootenai, Bonner County, Idaho. A year or so later, he got a job in the Last Chance mine, so the family packed up and moved out of state on Thanksgiving Day to the gold-mining town of Republic, in north-central Washington. Within a year, the Last Chance expelled its last gasp and shut down.

Charles found a job working on a city water plant project. When the project was completed, he was once again unemployed.

Even worse, he had contracted what was commonly called “miner’s consumption,” a wasting disease, usually pneumoconiosis, caused by the inhalation of silica, asbestos or some other kind of lung-destroying dust. The Cox kids were in the midst of a school year, so Charles moved without his family to Arizona and hoped the dry climate would help him breathe.

Gertrude, meanwhile, resumed her teaching career with a job in a school in Danville, Washington, just south of the Canadian border, and moved there with the children.

Down in the hot, dry Southwest, Charles’s health failed to improve. He died of pneumonia. The 1920 U.S. Census listed Gertrude as the head of the family, and as a widow living in Danville.

Teaching jobs, like mining jobs, came and went in rural Washington. The Coxes rented cheap apartments, sometimes boarded with other families, always trying to stay ahead of the bill collectors and keep everyone safe and fed. At one point, they moved to Bellingham on the west coast of Washington, and later to Battle Ground in the south-central part of the state.

It was around this same time that Beverly’s younger brother Norton, while sledding, slammed head-first into a car and died without ever regaining consciousness. The former family of seven had shrunk to four.

After Beverly graduated early from high school in Battle Ground, she returned to Bellingham to attend Normal School there and train to become a teacher like her mother. It wasn’t that she had a keen desire to emulate her mother’s career path, but Gertrude had convinced her that teaching would allow her to earn money to attend college later on and study something in which she had more interest.

Meanwhile, the moving continued. After Gertrude and Beverly taught in the same rural school in Washington in 1926 and took non-teaching jobs in Portland, Oregon, in 1927, Gertrude traveled to Craig, Alaska, to teach in the fall of 1928, while Beverly took a teaching position in rural Montana — educating just three pupils, all from the same family.

In order to get paid at the end of each month, Beverly had to borrow a horse and make a 20-mile, round-trip ride — in all seasons — to pick up her check and have a place to cash it.

Low on funds, the school was unable to pay her for a full year or to bring her back again for 1929-30. Beverly got her students through all their lessons by about March, she said, and then she bundled up her possessions and moved back to Portland.

There, finally, her fortunes began to change.

Her brother Ted, who was by this time married and living in Portland, invited his sister to live with him and his wife until Beverly got settled elsewhere. Ted was also the drummer in a four-man band, in which a handsome guy named Joseph Sabrowski was the piano player. Since group practice sessions took place at Ted’s house, Beverly and Joe had numerous opportunities to get acquainted and spend time with each other. Soon, she and this nice Catholic boy were an item.

Then in that summer of 1929, Beverly and Gertrude learned about and applied for a pair of teaching openings in Kenai. In July, Mr. William F. Parish, the principal of the Kenai territorial school, happened to be in Portland, so he came to see the two women. He offered them both positions, and they accepted.

Of course, a job in Alaska complicated Beverly’s love life.

Beverly and Gertrude had tickets for “the schoolteacher special” voyage on the steamship Alaska for Friday, Aug. 23, 1929, and Beverly and Joe decided to tie the knot before their departure.

“We were married on Monday,” she recalled, “and on Friday of that same week I was baptized at five o’clock in the afternoon. And at seven o’clock we left for Kenai.”

So one month before celebrating her 22nd birthday and just prior to beginning an Alaskan adventure that would span more than six decades, Nora Beverly Cox became a Catholic and a Sabrowski. She had never belonged to a church before, never been married before, never been north of the Canadian border before.

Her life would never be the same, as Part Two will demonstrate.