BOSTON — There was a day not so long ago when this country had squat to offer as far as hard ciders. And for those of us who came of age on this deliciously dryly-sweet boozy beverage, it kind of sucked.

Having spent my university years in Scotland, I took advantage of many a pint of hard cider to warm my soul during the bitter, damp seasons (11 months of the year) and make studying metaphysics more tolerable. But when I graduated and returned to the U.S., I was dismayed to discover so few choices on our shelves and in our bars. And what few there were rarely were worth drinking.

That was more than a few years ago. Today, we are awash in hard cider choices, a trend that has piggybacked on the craft beer wave. Sadly, most of them still aren’t worth drinking, tending to be either stupidly sweet or breathtakingly dry. After a while, I simply shrugged and chalked it up to the U.S. not having a strong cider culture, nor much history making it (at least compared to Europe).

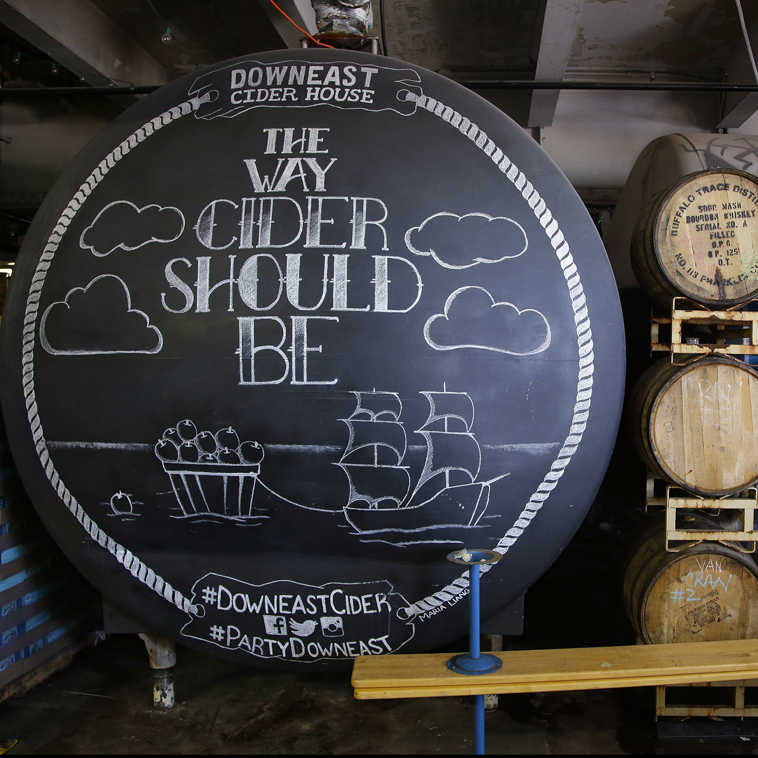

Then I spent this summer living (and drinking) in Boston, where Downeast Cider House ciders flow something akin to water. I first encountered the cider at a Cambridge bar, where the waitress told me it was produced in Maine. That turns out to be true mostly in spirit, despite the name. It’s a solidly Boston-based company (that started in Maine in 2012, but moved for reasons amusingly told via cartoons on the company’s website — http://downeastcider.com/history/ ).

And the company produces a deliciously murky cider. Wait… Murky?

Murky isn’t often a term associated with delicious. But roll with this one. The ciders I enjoyed as a too-young man were crisply, transparently amber. Downeast Cider House ciders are cloudy. I balked when my first pint was poured. But then I tasted. Clean and crisp, a little sweet, a little dry. Which is to say, a balanced cider. The sort of drink Americans have shown themselves not particularly adept at producing.

The company was started by Ross Brockman and Tyler Mosher during their final year at Bates College in Maine. Brockman’s brother, Matt, also joined the troupe. Why is their cider different? They’ll tell you it’s because they do everything from scratch. They’ll also mention that their ciders aren’t filtered, hence the murkiness. They are right, of course, but their motivation matters, too.

When Mosher and Brockman started playing around with making cider during college, they had a simple goal. They wanted to do something that stood out from other ciders being produced.

“There were two different types. The melted Jolly Ranchers, mass produced ciders,” Mosher said recently of ciders that tend to be candy sweet. “On the other side were small craft producers emulating old English ciders, dry ciders. So we decided to make a hard cider that tasted like fresh apples.”

The resulting ciders are refreshing and lightly sweet, but not cloying. My favorite is their “original,” which accounts for nearly three-quarters of the 17,000 barrels they expect to produce this year, a more than doubling of overall production over last year. So it would seem I’m not the only one impressed by their ciders.

Distribution of Downeast Cider House ciders is mostly at bars and by the can in New England, New York and New Jersey. They are worth hunting for.