I have mentioned before how history sometimes seems to fall into our respective laps completely out of the blue. This was certainly the case a number of years ago when Mary (otherwise known as Mollie) Montgomery Brackett’s truly amazing gold rush photographic album did just that.

Mollie’s photographic album is amazing in three ways, first, that it even survived the over 100 years since it was put together being in such a fragile condition, second for its contents, an all embracing snapshot in the life of Skagway citizens during the Klondike gold rush of 1898-1899, and third for how it was rediscovered.

The Bracketts

Mollie Brackett was married to Tom Brackett, one of George Augustus Brackett’s seven sons.

From almost the start of the Klondike gold rush, the 61-year old George Brackett, former mayor of Minneapolis, Minnesota and experienced railway builder, was a major player in Skagway’s early history and one of the prime movers and shakers about town. George Brackett arrived in gold rush Skagway intent on profiting by provisioning the horde of prospectors then invading the town. One of his sons preceded him to Skagway and started Brackett’s Trading Post, a small building which still survives to this day and is now located on the east side of Broadway just a bit north of Fifth Avenue. Selling groceries and general merchandise, the Bracketts soon out grew this building and built a large two-story store, office and home on the northwest corner of Third Avenue and Main Street – the “Mansion House” as Mollie called it. The family also became involved in enterprises in both Atlin and Dawson but George Brackett soon realized that easy transportation to the Yukon was vital for Skagway’s economic survival and it could also be highly profitable. So Mr. Brackett started construction of the Brackett Wagon Road that turned out to be a major engineering feat. When completed, it ran north from Skagway to White Pass City. Then it turned into a sled road from White Pass City to the Summit of White Pass and finally a trail that continued to Bennett, British Columbia.

In order to help him with his various enterprises, George Brackett called upon his seven sons and so on Feb. 4, 1898 The Skagway News reported that “Mr. and Mrs. T. T. [Thomas Thayer] Brackett are recent additions to Skaguay. Mr. Brackett is the son of George A. Brackett; Mrs. Brackett is an accomplished musician.” Born into a prosperous musical family in 1870, Mollie grew up singing and playing the piano. In her 20s she became a voice teacher. When she started taking photographs is unknown, but it may have started with her arrival in Skagway.

A Kodak

Like the cellphone camera of today, taking pictures with the new amateur cameras that became available in the late 1890s from Eastman Kodak and other companies became quite the rage.

They even had a name for it: Kodakery The Hawkeye Junior Camera advertised in the 1897 Sears, Roebuck catalog may have been the kind of camera Mollie Brackett used. That camera measured 4¼ by 4½ by 6 inches and weighed about 20 ounces and was covered with black grain leather. It had the ability to do time exposures and could hold both roll film and small glass plates. It took a picture measuring 3½ by 3½ inches. The speed of the lens could be regulated, which means it could take pictures in weak lighting conditions such as indoors. Price of the camera without the film was $7.20 while the price of a roll of sunlight film (12 exposures) was, 55 cents (that is around $208.80 and $15.95 in today’s dollars).

There are several pictures in Mollie’s album of others holding similar looking cameras. On the front cover of Mollie’s worn black album is embossed the word PHOTOGRAPHS and inside, inscribed in fading ink but with a bold feminine hand is written “Mary Montgomery Brackett, Skagway, Alaska, begins in 1898.” The album contains hundreds of small, oddly trimmed blue images pasted on the album’s crumbling, yellowed pages. These are cyanotype images. Cyanotype is a contact printing process (the print is the same size as the negative – in other words not enlarged) that was popular among amateur photographers of the late 19th and early 20th centuries because they could make their own inexpensive prints with sunlight and water, without a darkroom or an enlarger, although the roll of film negatives had to be conventionally processed. Mollie and her friend Mrs. Tuckerman probably made their own prints from film possibly developed by Mr. Tuckerman (who was apparently also an amateur photographer) or by one of the professional photography studios in town.

Glimpses of the past

What is unusual about the images is that they have all retained their color and clarity because they have been kept in their original album, mostly in the dark and in fairly good environmental conditions. What is also unusual about the photographs is that below most of the images, Mollie has written captions. Mollie’s album gives us precious glimpses into the past, like personal letters and diaries. Most professionally made photographs of the late 19th century were carefully composed on the ground glass of a large wood view camera mounted on a sturdy tripod. These needle-sharp images generally were formally posed and seldom show the spontaneity reflected by the humble snapshots made by the amateurs. The sharpness and clarity of the snapshots from the pages of Mollie’s gold rush photo album do not begin to match the quality of professional photographs of the day, yet they offer us priceless windows into the past. They show us the forgotten faces of people who, without these pictures, might be lost to history. They show us places that for some reason were forgotten by the professional photographers. They bring life to the past the way no professional image can. Mollie’s album provides a snapshot into her life with family and friends here in Skagway during the Klondike gold rush.

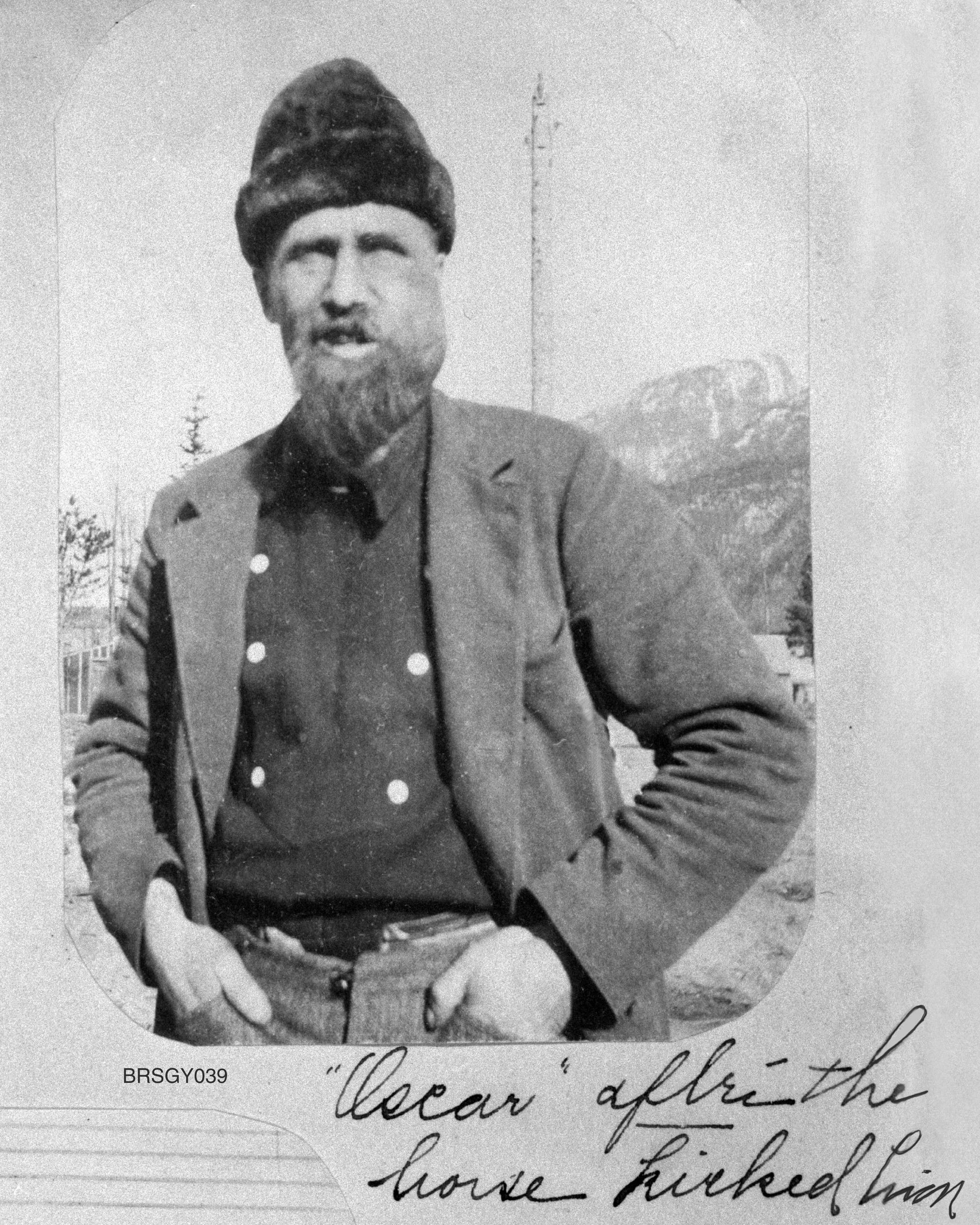

For example, there’s a picture of “Oscar after the horse kicked him” with his whole left side bulging out from his face. Boy, that must have hurt! Then there’s “Two little maids from Skagway” with Mollie and Mrs. Tuckerman sitting on a wood stave water pipe about to be installed in Main Street. Mollie was not the only woman with a camera, as her friend also had a small box camera. Another picture shows “The way we slept at the Summit, six in a bed, July 1898.” This was taken at the summit of the White Pass and all you see is a sea of blankets outlining human sized lumps inside of a tent.

Mollie seemed to like to take pictures of people asleep because there are also two photographs of hospital patients in beds, another picture of the railroad strikers sleeping in the Presbyterian Church, and a photograph I particularly like, of George Brackett, the patriarch of the Brackett clan and a major figure in gold rush Skagway, sound asleep on the couch in his home on Main Street.

Then there is the photograph of two men holding up “A huge halibut caught near Skagway, 1898.” The halibut is taller than the men.

Then there is a picture of “Old Bob, one of the few survivors [of] the original trail horses’ – a small, rather pathetic looking horse that apparently survived the horrors of the Dead Horse Trail. Mollie seemed to have an affinity for the pack animals for she documented the overloaded horses, burros, goats, and dogs on the White Pass Trail. She also photographed the dead horses in the Skagway River near town on April 1899.

‘Just as he was’

One of the most poignant images in the album is a photograph of Mollie’s husband, Tom Brackett. A young man dressed for an excursion with his bow tie slightly askew and looking at the photographer, his wife, with the towering mountains surrounding him and the Skagway River well below. Mollie wrote the caption to this fine snapshot of Tom: “Dear old Tom just as he was, August 1898” underlining “was.” Tom Brackett died of Typhoid fever on Feb. 26, 1901 in Portsmouth, New Hampshire. This indicates that Mollie probably put the album together sometime after Tom’s death although exactly how long after is unknown.

Sorely undercapitalized from the start, George Brackett built his wagon road but his dream of a railroad was crushed by the British-financed White Pass & Yukon Route, who bought him out. After that, and with the gold rush excitement over, the Bracketts left town. Tom Brackett presumably along with Mollie left Skagway on Oct. 14, 1900, never to return. After Tom’s death Mollie lived the life of a widow but stayed in the West. Mollie Brackett died in La Jolla, California (near San Diego) on July 22, 1939.

Ordinary life

What happened to her album for the next several decades is unknown.

Then it surfaced in the trunk of a car repossessed by a southern California auto salesman named Robert Wilson, Robert gave the album to his brother, Richard, who passed it on to a friend’s daughter Pattilyn Drewery, who lived in Alaska.

After Pattilyn’s untimely death in 1991, her family, knowing that she treasured the album because of its historical value, gave it to Pattilyn’s close friend, Pat Worcester. Pat, knowing that Anchorage Public Television station KAKM was looking for pictures of the gold rush for a Centennial documentary they were planning, brought the album to the attention of Tom Morgan, a producer and director for the station. Tom contacted Clay Alderson, Superintendent of Klondike Gold Rush National Historical Park in Skagway, who in turn mentioned the album’s existence to David Curl.

Curl, a photography professor at Kalamazoo College in Michigan, had worked for the park as a seasonal interpreter for a number of years beginning in 1993 and most recently helped digitize the park’s newly acquired Rapuzzi collection of historical photographs in 2007. Curl went to Anchorage in the spring of 1995, and (with Tom Morgan’s help) photographed just over 300 of the still-pristine cyanotype images and their captions with his Nikon FM-2 film camera and macro lens on a makeshift copy stand in a back room of the Anchorage public TV station (this was before digital scanning). So today we have a record of what ordinary life in Skagway and on the White Pass Trail was like during those exciting years of the Klondike gold rush.

Karl Gurcke is a Skagway historian who works at the National Park Service. He can be reached at karl_gurcke@nps.gov.

Information for this program was supplied by a book entitled One Woman’s Gold Rush: Snapshots from Mollie Brackett’s Lost Photo Album, 1898-1899 by Cynthia Brackett Driscoll and Dave Curl, published in 1996. If you have or know about a photograph album like Mollie’s or know of any letters, diaries or other information pertaining to Skagway’s history, please email the author. An earlier version of this article was read over the air on KHNS, the Haines public radio station.

• Karl Gurcke is a Skagway historian who works at the National Park Service. He can be reached at karl_gurcke@nps.gov.