The mystery of “Hauns cabin” unlocked something in me, and this is the story of how the life of a man born 135 years ago and long since dead has jarred loose and clarified a nearly 50-year-old memory of my own.

For me, the story began with research and writing earlier this year. My historian friend Gary and I were working on the history of some cabin ruins near the confluence of Mystery Creek and the Chickaloon River, in the northern portion of the Kenai National Wildlife Refuge. Gary had visited, photographed and documented the ruins back in 2003. Because he knew nothing about the history of the cabin, he had initially given it a geographical designation, but suddenly he notified me that he had opted for a new identifier. He wanted to change the name to “Hauns cabin.”

That’s the way he wrote it in an email to me: “Hauns,” no apostrophe.

“Who or what was Hauns”? I asked him. “I have no idea,” he answered.

“Then why do you want to change the name?” I said. In response he sent me a series of typewritten transcriptions from the 106-year-old, handwritten diary of a Chugach National Forest ranger named Keith McCullogh.

In his February 1914 ranger diary, McCullogh referred three times to “Hauns cabin,” written just as Gary had done. While patrolling the area, McCullogh and a traveling companion broke camp on the Chickaloon and “followed the river northerly for four miles. Open water and (snow) drifts forced us up on the bench and we proceeded through down timber on old burn until we struck trappers trail, following which we arrived at Hauns cabin 12 miles from the mouth of Chickaloon River near edge of timber on flats.”

McCullogh and partner spent the night there and noted on the following day that Harry Miller of Hope cruised by with his dog team while running a trap line from Little Indian Creek to the East Fork of the Chickaloon River. McCullogh departed the next morning.

After I digested this material, three things occurred to me: (1) Gary had traveled extensively in the Chickaloon area and could almost certainly tell from the descriptions that the location of “Hauns cabin” matched the ruins he had found and documented in 2003. (2) It was common in the early 1900s for miners from the Hope and Sunrise mining camps to supplement their incomes by trapping in the winters in the Chickaloon area. (3) Harry Miller, the man who’d mushed by McCullogh in February 1914, was just such a miner.

If Miller had been mining during the warm months and trapping on the Chickaloon during the cold ones, I decided, it was likely that “Haun,” too, had almost certainly been another Hope miner who’d done the same.

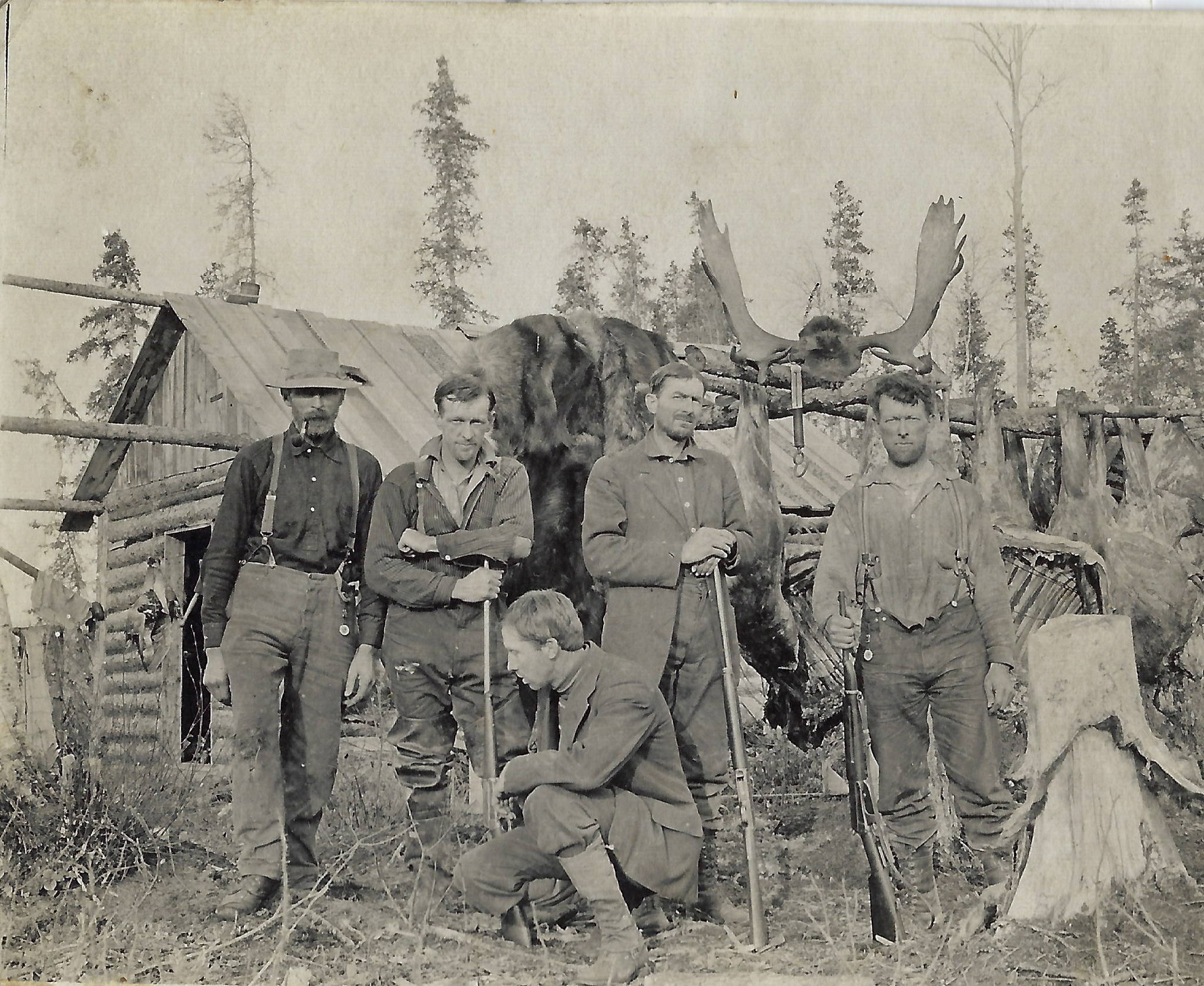

I did some more research. Mary J. Barry, in her history of mining on the Kenai Peninsula, provided the first clear pieces of the puzzle: Edgar Thomas Haun — born in California in 1885 and known variously as “Red,” “Pop” and “Red Hat”— had first come to Alaska in 1910 and had settled in Hope to become a placer miner.

For the rest of his long life, Haun had lived mainly in Hope, with frequent sojourns in California, and he was buried in the Hope Cemetery after his death in 1974, at the age of 89.

According to Barry, Haun worked for the Alaska Railroad in 1915, ran a ferry between Girdwood and Anchorage in the late 1910s, performed carpentry work at the Matanuska agricultural colony in 1936, mined on Resurrection and Palmer creeks out of Hope, and did trapping on the side.

His draft registration card from 1942 said he was living in Anchorage and working for the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers at Fort Richardson. At that time, Haun, age 57, stood 5-foot-9, weighed 192 pounds, and had hazel eyes and brown hair.

He also had frequent romances. In fact, he was married five times, often to women much younger than himself. His forays into matrimony included Ione, who was 19 when she and Ed, age 44, were counted in the 1930 U.S. Census, and Bertha, who was 37 when she married 63-year-old Ed in 1949. His final marriage, however, occurred in 1970 and was to Nellie, a woman two years his senior whom he had known for most of his life.

But the most interesting thing to me personally was this: From 1963 until the end of his life, Haun operated the Pay Streak Mining School, where he taught tourists and recreational miners how to pan and sluice for gold at his claim on Resurrection Creek.

If Haun had been operating such a “school” on the creek, I reasoned, it had to have been near the Resurrection Pass trailhead — a place easily reached by Hope visitors eager to watch an old-timer show them how it’s done. In fact, in about 1972 I had been part of a church youth group hiking the Resurrection Pass Trail from Hope to Cooper Landing, and I had a clear but incomplete memory of our group stopping along the creek when we encountered an old man sitting on the porch of his log cabin and playing a handsaw like a musical instrument.

Wouldn’t it be funny, and ironic, I thought, if that old man, who had played the saw so well and had entertained us for several minutes before we headed on down the trail, had been the Ed “Red Hat” Haun? I tried to remember whether the saw-player had been wearing a hat, but my foggy mental image of him refused to crystallize. I tried to recall whether I still knew anyone else who had been on that hike, but again I drew a blank.

So the memory nagged at me, hinting at truth without offering satisfaction.

Sometimes our lives contain fragments of memory that we can make no sense of because we lack the context necessary for full understanding. Did that bear charge me in a dream, or did that really happen? Did my father really let me drive the tractor by myself when I was 6, or had he been sitting behind me, one foot poised over the clutch, the other over the brake? Was our boat really attacked by an angry beaver protecting its home on the lake, or was that our neighbor teasing me?

Often we have no idea where to turn to find such answers. The questions, in fact, may seem too silly to ask. Perhaps the only person who would know for sure has already died or moved far away. Maybe we were too young to recall crucial details.

But occasionally a few pieces of life’s jigsaw puzzle do fall neatly, even surprisingly, into place. And such was the case this time.

For nearly 50 years, off and on, I had wondered about the man playing the saw on the porch that day, and I wanted to learn the truth. So I prepared myself to be wrong about Ed Haun, and then I sent an email query to Diane Olthuis of the Hope-Sunrise Historical Society.

She wrote back the next day: “The old man playing the saw was Ed Haun.”

In a later email, she added this: “Haun had Pay Streak Mining School on Resurrection Creek. At Pay Streak, Haun built a 14’x18’ log cabin.” And she sent me a photograph from 1972: Edgar Thomas Haun is sitting on a wooden chair on his porch. He is wearing a coral-colored plastic Stetson, a plaid shirt, dark trousers held up by suspenders, and a pair of XtraTufs. Between his legs is a handsaw, which he is playing for two female tourists, one sitting to each side of him.

History reached out across the decades.

• By Clark Fair, For the Peninsula Clarion