AUTHOR’S NOTE: Misfortune was written across the recent history of the Arlon Elwood “Jackson” Ball family. Ball’s father had been struck and killed by lightning in Connecticut in 1935. One of his sisters had served time in at least two reformatories in the 1930s and 1940s; another sister’s house had burned to the ground on the Kenai Peninsula in 1952. A younger brother had died in a one-car accident near Soldotna in 1958. Ten years later, it was Jackson’s turn for tragedy.

In the wee hours of a Saturday morning, Oct. 12, 1968, Lori Lancashire was sitting at the bar in Larry’s Club, an establishment owned by her parents, Rusty and Larry Lancashire. Lori was chatting with another woman when Jackson Ball approached her and said, “Go find your mother. She’s shooting pool at the Rig Bar.”

She saw no sense in Ball’s instruction and declined, but Ball insisted. Lori didn’t realize it immediately, but Ball was trying to get rid of her. He knew trouble was brewing, and he wanted her out of harm’s way. “Go find her,” he said, “and take this lady with you.”

Sometime after 3:30 a.m., as Lori Lancashire sat at the Rig Bar, watching her mother shoot pool, she saw a cop car drive by, lights flashing, siren blaring. Suddenly, Lori connected the dots. She called to her mother: “Come! They’re going to Dad’s!” Lori and Rusty headed straight for Larry’s Club and rushed inside.

Minutes earlier, officer David Ulfers of the Alaska State Troopers, responding to an urgent call for help, had arrived to find one man moaning just inside the entrance and another man lying face-up near the bar. The man near the door was Larry Edwards, and he was fresh from a fracas. The man on the floor was Jackson Ball, and he was dying.

Officer Ulfers reported that Ball had a hole in his neck and was bleeding heavily. Within a short time, he was dead.

Aftermath

At a hearing on Oct. 31, Phillip Howard Cook, who had been a Larry’s Club customer on the night of Ball’s death, testified that a fight “with a pile of guys involved” had started at one end of the bar. Cook said that he had tried to help bartender Larry Lancashire move the men and their skirmish outdoors; he also said that he heard Jerry Thomas Edwards, the accused shooter and the brother of the injured man, say, “Don’t hurt my brother!” and then threaten to get his gun.

Five to eight minutes after Edwards’s threat, reported Cook, the door to the bar flew open: “I saw Jerry first. Within seconds I saw Larry (Edwards) come in with his shirt off, and he fell down by the entrance…. Jerry paused and said, ‘Where is the fat guy?’ Jackson Ball raised up from the stool where he had been seated, took three or four steps towards Jerry with his hands raised up and said, ‘You can’t.’ Jerry pivoted and shot him.”

Cook further testified that Larry Lancashire then managed to take the gun (a .38-caliber revolver) away from Jerry Edwards and attempt to calm him down. Cook said Edwards had been “in a rage, yelling, screaming, cursing and staggering, saying, ‘I’m going to kill that fat man!’”

Many years later, one of Ball’s middle daughters, Kayleen, tracked down Officer David Ulfers, who she said told her that her father had been an innocent bystander — someone simply trying to stop the escalating violence — on the night he was shot.

Larry Edwards, brother of the shooter, spent time in Providence Hospital in Anchorage, where he was listed in fair condition. Jerry Edwards, who had arrived in Alaska only about a week before the shooting, was arraigned within hours of the incident and transferred to the state jail in Anchorage.

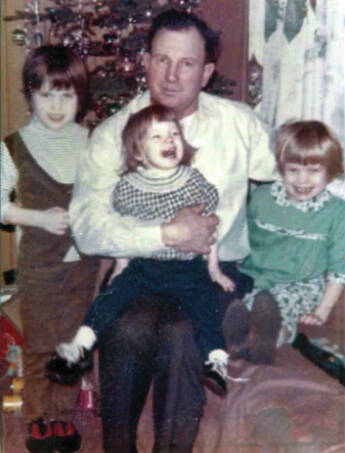

Initially, Jerry Edwards was charged with the first-degree murder of Arlon Elwood “Jackson” Ball, whose survivors included his mother Margaret, his wife Mary and their four daughters (Margaret, 9; Mary, 7; Kayleen, 4; and Kim, 16 months), his older brother Robert and three of his four sisters (Lillian, Amy and Gerda). Missing from the list were Johnny, who had died a decade earlier, and Esther, the troubled sister who also may have died.

Services for Ball were held at Green Memorial Chapel in Anchorage, and he was buried in the city’s Angelus Memorial Park. In the aftermath of Jackson’s death, wife Margaret took her daughters out of Alaska and moved back to her home state of Connecticut.

Jerry Edwards began his legal defense with a court-appointed lawyer, who later withdrew from the case in favor of Edwards’s own attorney. When the case was sent to the grand jury in mid-November, the charge had been reduced to second-degree murder.

In May 1969, Edwards pleaded guilty to a lesser charge, manslaughter, and was sentenced in Superior Court to five years in prison.

But the legal troubles for Jerry Edwards did not end when the termination of his prison sentence. There were minor problems — traffic fines, lawsuits to force the payment of bad debts — and then there were the 1977 charges of assault with a dangerous weapon and burglary in a dwelling. Edwards pleaded no contest to both.

“The exchange of gunfire came on Feb. 22 during the defendant’s entry into the home of Bruce Ingersoll Jr. on Brandt Way (in Anchorage),” reported the Anchorage Daily Times. “Both Ingersoll and Edwards were hit. Ingersoll was treated and released, and Edwards was hospitalized and arrested.”

In October 1969, on the one-year anniversary of Jackson Ball’s death, a brief tribute to him from his wife and one of his daughters appeared in a New London, Connecticut, newspaper. The tribute, written in verse, was entitled “IN MEMORIAM, In Loving Memory of Arlon E. Ball, Who Passed Away Oct. 12, 1968.” It was signed “Sadly missed by WIFE AND DAUGHTER.”

This sorrowful note, then, might have been the end of the public story concerning the life and death of Jackson Ball. There was, however, more to be told — another chapter that no one saw coming.