Unbeknownst to most folks, this past Tuesday was the International Day for Biological Diversity. The United Nations declared May 22 as the day to help make people aware of the importance of biodiversity, 25 years after the Convention on Biological Diversity was approved as a multilateral treaty in late 1993 by 196 countries. The convention has three main goals: the conservation of biological diversity, the sustainable use of its components, and the fair and equitable sharing of benefits arising from genetic resources.

Given that one of the primary legislative purposes of the Kenai National Wildlife Refuge is to “conserve fish and wildlife populations and habitats in their natural diversity,” it is not surprising we have taken this message to heart.

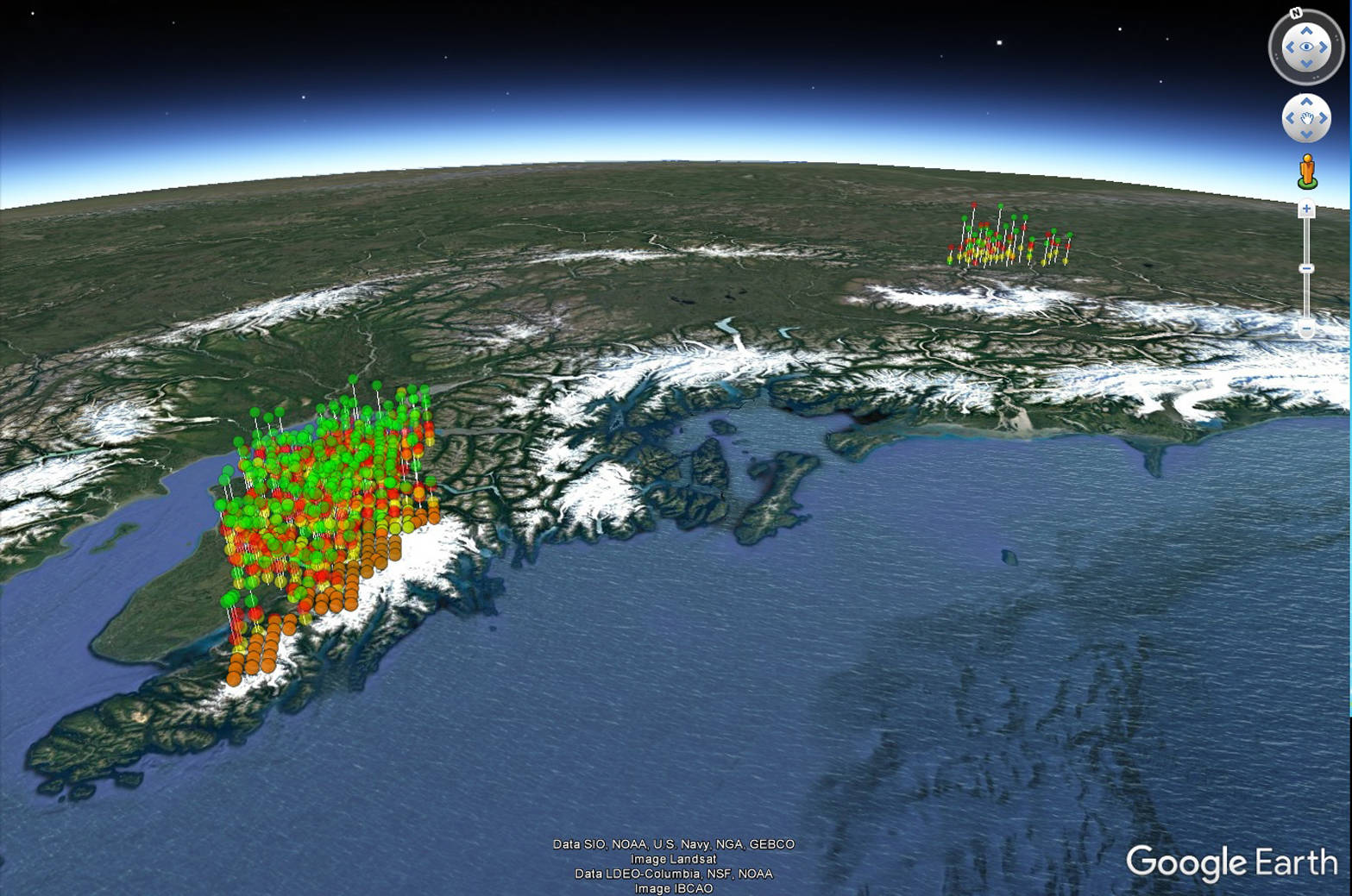

In 2004, 2006 and 2008, we collaborated with the U.S. Forest Inventory and Analysis program to survey species diversity on 259 plots spaced at five-kilometer intervals across the 2 million-acre Kenai refuge. It was not an exhaustive survey, but it was comprehensive in its taxonomic scope. Just as importantly, it gave us good spatial data for over 1,000 species of birds, invertebrates and plants!

Refuge staff continue to build our species inventory. We now have documented 2,138 species, including 207 vertebrates, 826 invertebrates, 523 vascular plants, 182 mosses and liverworts, 370 fungi and 30 unicellular organisms.

Of these, more than 95 percent are considered native species. One hundred species are nonnative, but the good news is that we believe 19 were extirpated from the refuge. What has really sped up our inventorying of biodiversity in recent years is the use of Next Generation Sequencing to identify species through genetic “barcodes.”

We recently had the opportunity to apply our survey approach on Tetlin National Wildlife Refuge near Tok. Again collaborating with the Forest Inventory and Analysis, we identified 229 species of birds, invertebrates and vascular plants on just 26 plots.

Here’s where the story gets more interesting. Tetlin and Kenai refuges are ecologically similar (or so it would seem) in many respects. They are both part of the boreal biome, heavily forested by white and black spruce, white birch and aspen, and inhabited by moose, caribou, lynx, wolves and bear. Fire is a big ecological driver in both systems.

So you’d think species diversity on both refuges would be similar — but that turned out to be only partially true. Of 80 bird species detected during the two surveys, 29 percent were found on both refuges. Of 370 vascular plant species, 16 percent occurred on both refuges. So there is quite a bit of commonality between the two boreal systems, at least among those taxonomic groups.

But of 338 invertebrates found in total during these surveys, only four species (1 percent) were shared by both Kenai and Tetlin refuges!

This is a stunning outcome if you’re an ecologist. Within the discipline of conservation biology, ecologists and managers often assume that if habitat is provided for an “umbrella” species that needs large landscapes, such as brown bears, then other species which require smaller areas are protected as well.

Our finding suggests that while this may be true for each conservation unit, in this case a national wildlife refuge, it isn’t safe to assume that both units conserve the same biodiversity despite their similar appearance.

Admittedly, the methods used were different. When we surveyed the Kenai refuge with the Forest Inventory and Analysis more than 10 years ago, genetic identification using Next Generation Sequencing was not a viable method.

So Matt Bowser, our refuge entomologist, had to resort to morphological identification. This is a tried-and-true method, but it is painfully laborious and slow, and generally requires adult specimens in good condition.

In contrast, at Tetlin refuge, we used Next Generation Sequencing to identify insects and other invertebrates quickly from sweepnet samples stored in RV antifreeze. The samples are homogenized (ground up) anyways for genetic analysis, so neither their age nor condition matters for identification purposes.

Still, our work suggests there is much more to discover about biodiversity in Alaska. These two surveys resulted in the identification of 1,249 species over a combined acreage of 2.5 million acres, which represents less than 0.6 percent of the state.

What’s the big rush? A paper published just this week in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences reveals that farmed poultry today makes up 70 percent of all birds (by weight) on the planet, with just 30 percent being wild. The picture is even more stark for mammals – 60 percent of all mammals on Earth are livestock, mostly cattle and pigs, 36 percent are human and just 4 percent are wild animals.

And as we enter a geologic age that some scientists now call the Anthropocene, many predict we are entering a sixth great extinction event, driven by a rapidly warming climate that could cause the loss of 40 percent of species worldwide. This is a big deal. The last big extinction was 66 million years ago when dinosaurs were snuffed out by rapid climate change in the aftermath of an asteroid cratering the Yucatan Peninsula.

So pause just for a moment to appreciate that almost 200 countries think enough of this looming problem to declare the International Day for Biological Diversity. Bottoms up!

Dr. John Morton is the supervisory biologist at Kenai National Wildlife Refuge. Find more Refuge Notebook articles (1999-present) at https://www.fws.gov/refuge/Kenai/community/refuge_notebook.html.