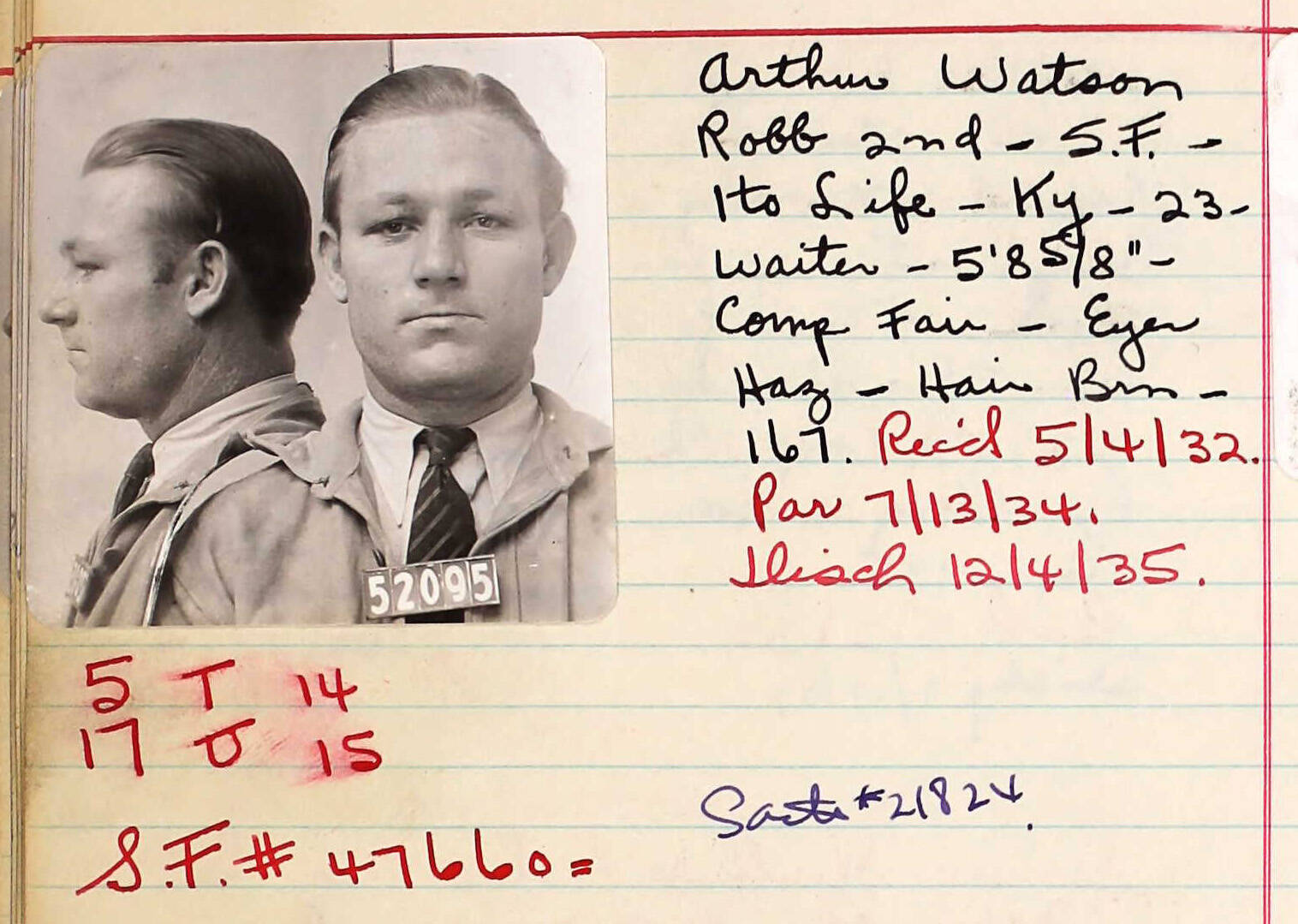

AUTHOR’S NOTE: In his Soldotna motel on Dec. 18. 1961, Arthur Vernon Watson shot and killed homesteader Marion Grissom. Although he claimed self-defense, a grand jury indicted him for first-degree murder. Watson, who was 53 at the time of the shooting, had a long criminal history that began with minor offenses and escalated quickly.

Well before he shot and killed a man in Soldotna in 1961, Arthur Vernon Watson was considered trouble.

Watson was 21 years old when he was arrested for vagrancy in Los Angeles in March 1930 and spent four days in jail. In 1932 — after a second vagrancy charge in 1931 — he was arrested for robbery in San Francisco and was sentenced to San Quentin state prison. He was released on parole in July 1934.

In March 1935, he married Thelma Anderson in Reno, Nevada, but even matrimony didn’t steer him clear of criminal behavior. A month after the wedding, he was arrested for disorderly conduct in Montgomery, Alabama. Three months after that, he was nabbed for carrying a concealed weapon in St. Louis.

Thelma testified in 1940 that she had known about Arthur’s time in San Quentin but had been convinced that she could “reform him.” She believed she could keep him away from bad influences — “his so-called friends.”

Unfortunately, she was not much of a fortune teller.

Thelma and Arthur were unemployed when they tied the knot, and in Memphis, Tennessee, they applied for government assistance. When Arthur failed to find steady employment, he left Thelma in St. Louis and traveled to California to look for work. He pledged to send her money when he could so she could join him.

Months later, without hearing from Arthur, she enlisted her brother’s help to track him down in Los Angeles. Reunited, they quarreled constantly for a month before she moved out. In her testimony, she said she hoped he’d get his act together and then get back together with her. By 1940, she had received only a single letter from Arthur, and he was on his way to his first hitch in a federal prison.

Despite being “heartbroken” and despite urgings from her family to dump Arthur once and for all, she said in 1940 that she still cared for him “deeply.” She said her family members “cannot realize that one can continue to love a person even though reconciliation does not seem possible.”

She said she would “never get a divorce” from Arthur. Once again, she wasn’t much of a soothsayer. They were divorced by 1947.

Arthur Watson had been arrested again in 1935 and 1936 — for loitering in Macon, Georgia, and on suspicion of forgery in Los Angeles. He spent several months in jail 1937 after being arrested in Sacramento, California, while using “Earnest A. Watson” as a pseudonym. Again posing as Earnest, he was arrested in Nevada City, California, in the spring of 1939.

But it was his actions in 1940 that landed him in long-term federal custody.

In San Francisco on Jan. 19, he quarreled in a night club and then ran when police arrived. He tried to hide in a nearby basement, but a pair of cops trapped him inside. When he surrendered, Watson turned over two handguns and told the officers, “I could have killed you both. But I do not believe in killing.”

The officers had Watson lead them to the hotel in which he had been staying, and there they discovered items that had been stolen on Jan. 2 from a rural post office near the Yosemite Valley.

Watson and two other men had stolen cash, blank money orders and other items at gunpoint from the postmaster, and then tied up the postmaster and his wife before fleeing in a stolen car. Watson confessed to the crime but claimed to have “forgotten” the names of his accomplices (who were later nabbed, regardless). He also admitted to a number of other crimes.

Three months later, he was sentenced to 25 years in federal prison.

He began his sentence in McNeil Island penitentiary in Washington and was soon transferred to Leavenworth prison in Kansas. By 1943 he was transferred again, this time to the penitentiary in Atlanta, and he probably would have served out his term there if he had behaved properly.

In Atlanta, Watson’s actions — fights with other prisoners, disorderly conduct, possession of contraband, and many other offenses — caused problems for himself and prison officials, but the action that propelled him back across the country and added an additional five years to his sentence occurred in November 1945.

Watson and a fellow inmate named Anthony Zullo had been gambling on and arguing about a game of bocce ball. Both men had apparently threatened each other, but Watson had decided to end the threat. While Zullo was performing prison barbering duties, Watson approached from behind with a 3-foot length of 2×4, with a carved handle on one end and a towel wrapped around the other end to deaden the sound of the impact.

The blow fractured Zullo’s skull. Watson was separated from other inmates and eventually tried in court. In November 1947, he entered Alcatraz Federal Penitentiary, near San Francisco.

His behavior there did not much improve. He had a fistfight with an inmate in 1948, another fight in 1950, and another one in 1951. He flouted prison rules, spent time in solitary confinement, and lost privileges and good-behavior points. In 1955, nevertheless, a Georgia court ruled that his two sentences should run concurrently instead of consecutively.

The Alaska Connection

In early 1956, he was released on parole and, with permission from officials monitoring his case, he moved to Alaska for the first time.

Anchorage provided Watson with a change of scenery but failed to significantly affect his demeanor. In his few months in the Last Frontier, he landed a job and then was fired. He was also arrested for fighting. His firing, reported his parole officer, “stemmed from jealousy of fellow workers because of his uncanny gambling successes.” The P.O. warned Watson that continued misbehavior could land him back to Alcatraz.

By July he was in California again and was soon living with and working for his sister, Patricia, the owner of a small hotel in San Francisco. She told Arthur’s parole officer that Watson had an “Eskimo girlfriend” in Alaska and that she had encouraged Arthur to send her plane fare.

He did. The girlfriend joined Arthur in California, and the couple soon expressed an interest in getting married and having more independence. Patricia and the P.O. gave their blessings on both counts.

There is a record of an Arthur V. Watson marrying an Alma Lee in November 1956 in San Francisco. Probably this was the union of Arthur and his Alaska girlfriend. Nevertheless, it didn’t last.

In January 1959, an intoxicated Arthur Vernon Watson, whom one newspaper called a “San Francisco brewer,” drove a station wagon past a stop sign and through an intersection at about 40 miles per hour and smashed into another car, which then collided with a third vehicle. Watson was originally charged with a felony, but his offense was later reduced to a misdemeanor. He escaped with only a $100 fine.

The lone passenger in Watson’s car was treated for a possible fractured nose and facial bones. She was 62-year-old Elizabeth Cecile (“Beth”) Kron, a widow and 20-year civilian employee for the U.S. Army. In November, Mrs. Kron became the latest Mrs. Watson.

The next year, Arthur Watson returned to Anchorage, this time with his new bride. They began to explore business opportunities, and in the fall of 1960 that exploration led them to Soldotna.

TO BE CONTINUED….