Gardens have held a special place in many artists’ lives, and their creativity was much the better for it.

Writer Sir Walter Scott gardened to distance his mind from debt. George Bernard Shaw crafted plays in a sophisticated yet modest garden hut. Impressionist painter Claude Monet treasured his kitchen garden.

“Gardens were really extensions of their art,” said Derek Fell, author of the new “Monet’s Palate Cookbook” (Gibbs-Smith).

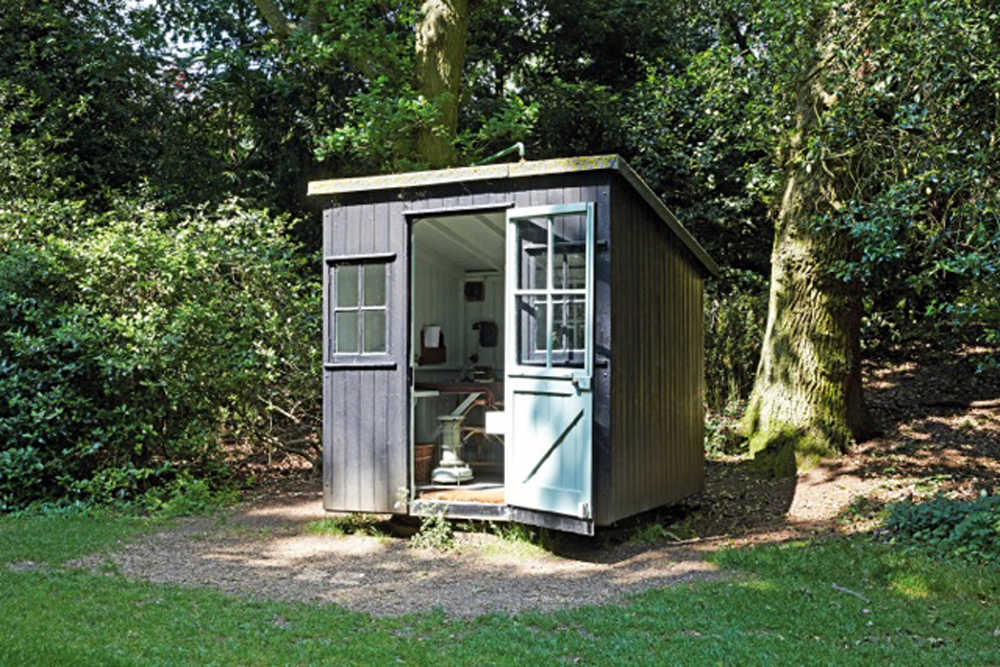

Some dug deep into the mechanics of gardening. Shaw, for example, was a vegetarian who grew vegetables, tended an orchard and raised bees at his rural Hertfordshire home in England, dubbed Shaw’s Corner. He wrote “Pygmalion” and “Saint Joan,” two of his most celebrated plays, in a small but intricate writer’s shed; it sat on a home-built turntable that could be rotated to follow the warming sun in winter or the cool shade in summer.

Shaw died at 94 after falling off a ladder while pruning a fruit tree.

John Ruskin, a Victorian-era art critic, painter and conservationist, was another hands-on gardener.

“He studied how everything grew very carefully, not only with his artist’s eye but also with his mind — as a social and environmental reformer,” said Jackie Bennett, author of “The Writer’s Garden” (Francis Lincoln Ltd., 2014).

“No words, no thoughts can measure the possible change for good which energetic and tender care of the wild herbs of the fields and trees of the wood might bring . to the bodily pleasure and the mental power of man,” Ruskin wrote.

Leonard and Virginia Woolf lived what they called a life of “ramshackle informality” at Monk’s House, a country retreat in East Sussex, England, that they transformed from overgrown land into garden rooms, brick walkways and an orchard.

Leonard, an author, editor and political theorist, was the planter, while Virginia, the novelist and critic, was more of an observer. She “experienced ‘profound’ pleasure in the ‘fertility and wildness’ of the gardens,” Bennett said. “Gardens feature strongly in her work.”

“. We are safe in our garden, and it’s the most I can do to get Leonard to leave it,” Virginia wrote in one of her diaries.

Other notable gardener-artists include:

— Paul Cezanne, the French Post-Impressionist painter. “His favorite pastime was going into the countryside and finding nature reclaiming man’s domain,” Fell said. “Things like roofs collapsing and ivy growing through windows. Many of his paintings fit that theme.”

— Monet, famed for his flower gardens at Giverny, France, also was fond of heirloom vegetables. “He was first to introduce zucchini into Normandy gardens as a result of finding seeds in an Italian market, and also Chinese artichokes — a tuber related to clover with a nutty flavor,” Fell said.

— Rudyard Kipling, who wrote “The Glory of the Garden” — a poetic tribute to gardeners everywhere. Money from Kipling’s 1907 Nobel Prize in Literature was used to improve his gardens, Bennett said.

And then there was poet Rupert Brooke, who perhaps said it best for all aspiring gardeners and garden writers: “I do not pretend to understand Nature, but I get on very well with her.”

More recommended reading:

“Virginia Woolf’s Garden,” by Caroline Zoob (Jacqui Small, LLP, 2013 )

“Monet’s Garden: Through the Seasons at Giverny,” by Vivian Russell (Francis Lincoln Ltd., 1995)

Online:

The Kipling Society has the poem “The Glory of the Garden” at http://www.kiplingsociety.co.uk/poems_garden.htm