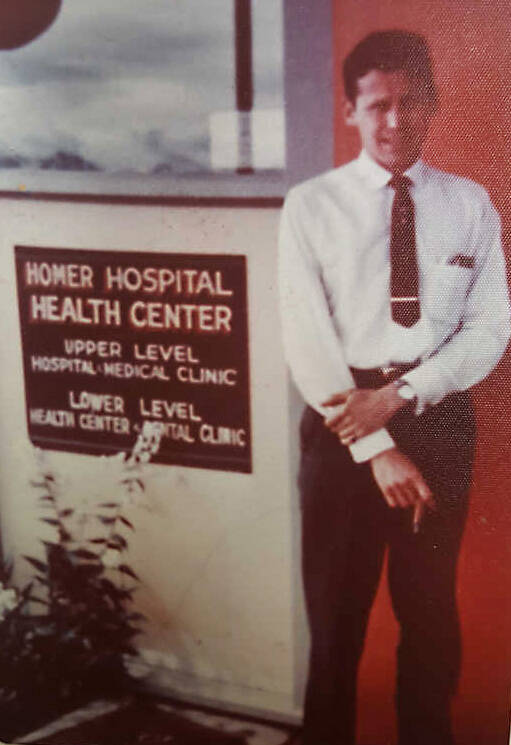

When Dr. John Fenger glimpsed into the operatory in the old Homer Hospital Health Center one day in 1961, he witnessed an unusual tableau: Dr. Calvin Fair, a visiting dentist from Soldotna, stood over a patient, with blood evident on the dentist and on the patient’s bib and mouth. On the floor, unconscious, lay Dr. Fair’s wife, Jane, who had been assisting with the removal of a difficult, impacted wisdom tooth.

Jane Fair, who was pregnant at the time, had been suctioning blood and saliva from the patient’s mouth when she had begun feeling lightheaded. She passed out as her husband pried and probed at the impaction site.

Dr. Fenger quickly assessed the situation. Referring to both patient and assistant, he asked Fair which one he needed help with. “He looked at Jane on the floor,” remembered Fair years later, “and said, ‘Oh, she’ll be all right.’ Then he picked up the suction and helped with the impaction.”

In the early days of formal medicine in Homer, doctors and dentists were often forced to improvise. After Dr. Fair moved with his family to Soldotna in October 1960, Dr. Fenger, Homer’s first resident physician and the chief-of-staff at the town’s four-year-old hospital, wrote to invite Fair to work there a few days each month. (Homer got its first resident dentist in October 1962 when Dr. Lloyd Barrow moved to town. Dr. Bill Marley became a longer-term solution a few years later.)

Dr. Fair, whose wife had just unceremoniously ended her career as a part-time assistant, called the dental equipment at Homer Hospital “ancient but serviceable,” noting that “suction was (provided by) an old Sears canister vacuum cleaner.”

But making do with what was available was a way of life for Dr. Fenger and his staff of Homer nurses — his wife Grace, plus Wilma Cowgill, Helen Alm and Kay Cowles.

Doctor and staff tended to the broken leg of Bruce Turkington and broken pinky of Peggy Larson, the crushed knuckle of David Cooper, and the fractured arm of Brent Johnson. Fenger performed school physicals for student athletes, delivered babies (including one of his own), made occasional house calls, and attended to the common ailments arising in any community.

In 1962, when a young Otto Kilcher was playing on his family’s tree swing, he somehow—according to a report in the Cook Inlet Courier—“became impaled on a tine of the mower bar which had been parked too close…. Otto was alone at the time and had to push himself off from the sharp pointed tine.”

His mother rushed Otto to Dr. Fenger and praised the doctor later for “a most dexterous job” in applying 22 stitches to her son’s wound.

Dr. Fenger, who could be prickly at times, was also compassionate and hard working. Sandra Sonnichsen referred to him as “the gentlest, kindest man.” Nancy Rehder Porter called him “a Godsend to our town.” He served Homer’s medical needs for most of a decade, starting in 1956.

Early medicine in Homer

Prior to 1956, the residents of Homer had relied primarily on visiting doctors, non-physician medical assistance or trips out of town to doctors in Seldovia, Seward, Anchorage or out of state.

Local medical alternatives included assistance from Homer pharmacists Howard Myhill and Vern Mutch, former U.S. Army medic Paul Banks, and women with nursing degrees.

Homer residents sometimes came for medical help to Myhill, who had once been a registered assistant pharmacist in Colorado but who never became registered in Alaska. Myhill worked at Mutch’s drugstore on Pioneer Street and came to be considered a local medical expert. He pulled teeth, delivered babies and even performed rudimentary veterinary procedures from time to time.

Out of town, industrial centers such as Seldovia and Seward were the earliest communities to have doctors and dentists of their own. Anchorage soon followed suit.

Seward, with its railroad, shipping and fishing industries, boasted some of the Kenai Peninsula’s first medical professionals, starting in 1903. Early Seward physicians with some of the longest tenures included Dr. Joseph Herman Romig and Dr. John A. Baughman. Dentist Dr. Russell Wagner began his dental practice in the 1930s and continued to serve the town’s needs until the mid-1960s.

For much of Seward’s history, the community had at least one hospital or large clinic to act as a draw for aspiring doctors.

Seldovia, with its fishing and canning industries, received its first resident physician in 1916 when Dr. Isam Flannery Burgin arrived in town. Burgin quickly came to prefer fox farming over medicine, as did his brother, Dr. Frank Burgin, a dentist who came to Alaska a year later.

Anchorage dentist Dr. Clayton Pollard practiced occasionally in Seldovia in about 1920, and, after he retired to Kasilof in about 1940, sometimes traveled to offer his dental services to Seldovia and Homer residents.

Generally speaking, physicians came and went in Seldovia. Dr. Russell Jackson arrived there about a year after Dr. Fenger came to Homer. Their Kenai Peninsula careers overlapped for about four years. Other Seldovia doctors during this time included Dr. Cary Whitehead and Dr. Osric Armstrong.

The original Homer Hospital Health Center opened in 1956 and was supported financially by the Homer Public Utilities District, predecessor of the City of Homer.

Fenger Origins

John Berg Fenger was born Feb. 15, 1923, in Evanston, Illinois, into a family with a rich medical and maritime history. Christian Fenger, born in 1773, had been physician to the King of Denmark. Another Christian Fenger had been a Chicago pathologist who taught surgery techniques to the Mayo brothers.

John, whose family nickname was Jack, grew up in Hamburg, N.Y. After graduating from high school, he attended a year of college and in 1943 enlisted in the U.S. Army. He became a first lieutenant in the Army’s elite 10th Mountain Division.

In the latter stages of World War II, he served on a troop ship crossing the Pacific to join in the anticipated invasion of Japan. During their crossing, however, U.S. air forces deployed atomic bombs over the Japanese cities of Hiroshima and Nagasaki and effectively ended the conflict. As a result, Fenger’s troops were diverted to Okinawa to perform clean-up duties, including the destruction of Japanese ammunition dumps.

During this time, Fenger also had the opportunity to visit many South Pacific islands and atolls. It was an area he would remember 20 years later when he was ready to leave Alaska for a change of scenery.

After the war, Fenger attended Lehigh University in Bethlehem, Penn., and then enrolled in the University of Buffalo’s medical school. In 1954, he found himself back on the high seas, but in a very different climate than the South Pacific.

Fresh from his work at Colorado General Hospital in Denver, Fenger drove north with fellow Denver physicians Helen and Robert Whaley, who were heading to Anchorage to begin their own medical careers. Fenger and the Whaleys remained close friends for many years.

John Fenger became the physician-in-charge of the medical vessel Hygiene, an Alaska Department of Health clinic boat used to deliver general health services to residents in isolated coastline communities, particularly on the Alaska Peninsula and in the Aleutian Islands.

The ship, formerly in service in Southeast Alaska and then out of service for several years, had been reconditioned and reactivated to combat Alaska’s severe problem with tuberculosis. The medical staff aboard included a nurse named Grace Heutink, who had spent the previous 17 months in Alaska’s anti-tuberculosis vaccination program.

In a nursing journal prior her arrival in Alaska, Heutink had seen an ad for positions available in the Territory: “Nurse wanted in Alaska. Must be free to travel. Salary $427 plus per diem.” She applied, and in May 1953 found herself vaccinating Alaskans for the Indian Health Service. By mid-September 1954 she was shipping out with Dr. Fenger.

“The Aleutian storms were vicious,” she told an Alaska journal of medicine, “and everything written about them is true. Sometimes the ship would roll 45 degrees either way, and you would wonder if she would ever right herself again.”

Heutink survived the storms and enjoyed the work. She also fell in love with Dr. Fenger.