Previous histories of Homer and the north shore of Kachemak Bay have taken a broad perspective, such as Janet Klein’s “A History of Kachemak Bay, the Country, the Communities” (1987, Homer Society of Natural History) or her 2008 revision.

Other books look at the north shore through the words of the early settlers, such as Walt and Elsa Pedersen’s “A Small History of the Western Kenai” (1978, Adams Press).

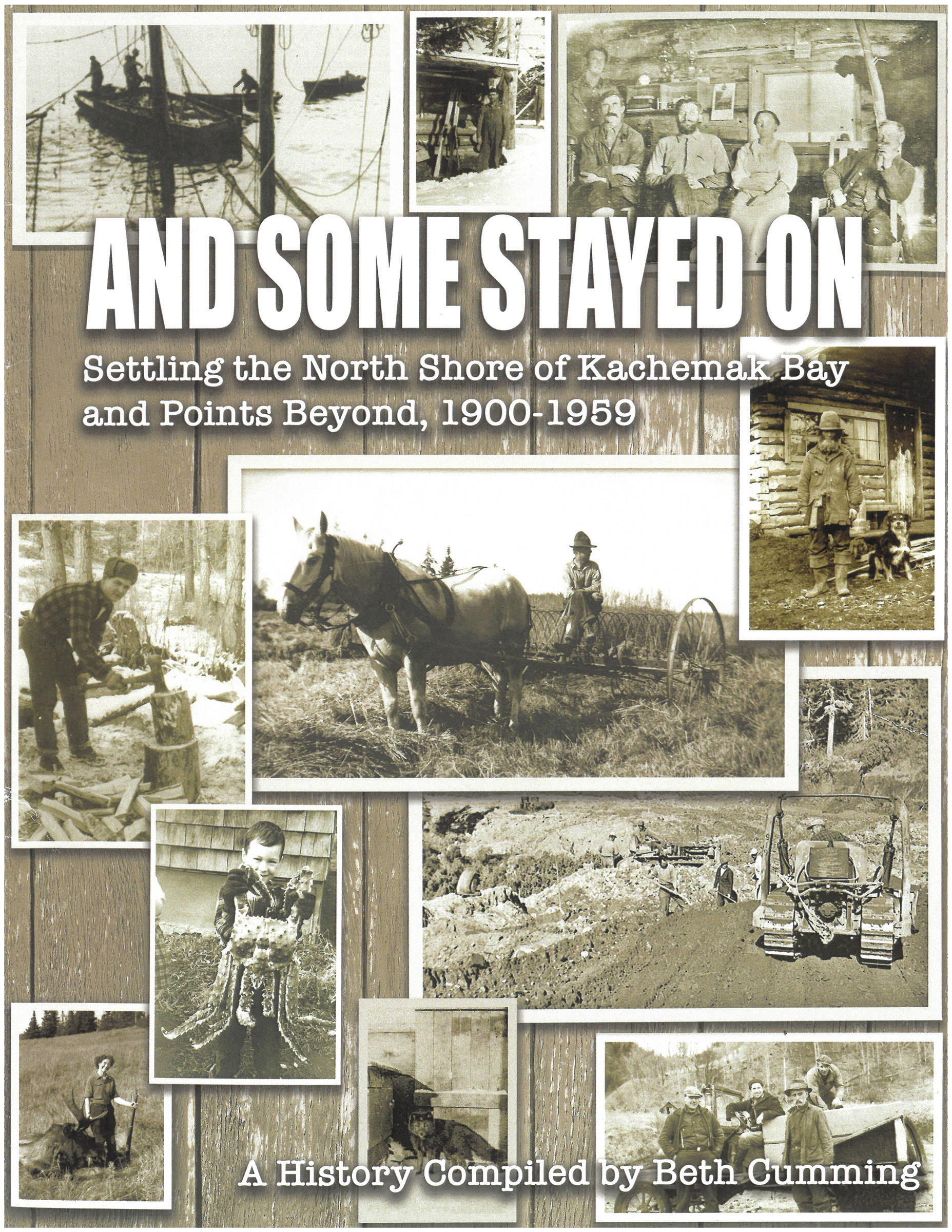

A book published this month by the Pratt Museum through the help of the Patrons of the Pratt Society, or POPS, combines that broad perspective with personal stories. Using narratives and family photographs, “And Some Stayed On: Settling the North Shore of Kachemak Bay and Points Beyond, 1900-1959,” compiled by Beth Cumming, covers the 60 years of Homer’s growth from a cluster of shacks on the Homer Spit to its beginning as a town with roads, public utilities, a dock and harbor, a hospital, and year-round employment.

The book also includes stories of Alaska Native people who lived in the land the Dena’ina called Tuggeght before and as European and Lower 48 settlers arrived.

A launch and book signing party for the book will take place from noon to 2 p.m. on Nov. 30 at the Pratt Museum, with another signing from 5-7 p.m. Friday, Dec. 6, also at the Pratt during a First Friday exhibit opening. Copies are on sale exclusively at the museum for $30, with proceeds going to the museum or to support more printings.

Cumming, the book’s editor and sometimes author as well as compiler, said she wanted “And Some Stayed On” to be more than a recitation of facts — “John Doe and his wife Betty came to Homer in 1937 and they did this and they had four children and their names,” she said.

“I wanted the whole book to give a feeling about what was going on without, my hope was, not being boring,” Cumming said. “I want it to be readable, but at the same time, give a picture of what life was like at a certain time.”

“And Some Stayed On” includes an account from the late 1800s with an excerpt about namesake Homer Pennock from Klein’s “Kachemak Bay Communities.” Pennock, the manager of a crew with the Alaska Gold Mining Company, came to Homer in 1896 with the group and built a small settlement on the Spit, later named after him.

The book is divided by decades or five-year periods, with a collection of photos and a history of the period written by retired Homer News reporter and writer Jan O’Meara, who is also the POPS secretary. Each section contains narratives compiled by Cumming from her own interviews, other books and articles, or written by a pioneer. Photographs generously accompany the text.

“And Some Stayed On” came about in 2006 when Cumming, former Pratt museum director Michael Hawfield and O’Meara put together an exhibit, “Making Ourselves at Home: Creating a Community on the Benchlands of Kachemak Bay.”

“The purpose of that exhibit was to do interviews with the pioneers who were fast passing,” O’Meara said.

That exhibit showed at the Pratt and the Homer Airport, and now is at the Homer Senior Center. Cumming had the idea to make a book based on stories in the exhibit. It took her 13 years of research and interviews and one solid year of writing and editing with O’Meara to make the book happen. POPS paid printing and productions costs. POPS, which once organized the annual quilt raffle for the museum, advocates for and fundraises for the Pratt.

“We decided we should pay for the printing, and so we did,” O’Meara said.

In addition to raising money for the Pratt, Cumming said “And Some Stayed On” also fits in with the museum’s mission statement “to strengthen relationships between people and place through stories relevant to Kachemak Bay.”

“It is one way the objectives of the mission statement are carried out,” she said. “It’s telling history … It’s like an exhibit.”

In selecting people’s stories, Cumming wanted to be as inclusive as possible. Names familiar as Homer landmarks, like Miller’s Landing or Paul Banks, are included, but the book includes more recent arrivals third-generation families might call newcomers. It also acknowledges the stories of Alaska Native families like Bill Choate and his mother, Vern Choate Langsdale.

Despite her best intentions, in her preface Cumming notes how trying to be inclusive proved to be unsuccessful. She sought a cross section of Homer life, but wound up getting stories and photographs of people already well known.

“So if the people seem quite above average, maybe it’s because they were, and why they were suggested to me as possible subjects,” she writes.

Cumming also faced another challenge: She compiled the stories with the cooperation of surviving family members. Some told of events other family found objectionable and thus some accounts have been sanitized.

“I wanted to give an overall picture of what life was like, and to get that I wanted to include the stories of, their representative stories,” she said. “I was somewhat disappointed in ending up mainly with stories of people where the story was acceptable to put in a public book, and leaving out stories that might be a reflection on the families.”

Still, some families agreed to tell stories that include the hard and sometimes harsh side of early pioneer life like alcoholism and abuse.

“I think that anybody who writes this type of history has to admit that it might not be a true representation of life, but rather representative of socially more acceptable stories,” Cumming said. “… I wanted the book to be used as a reference for some social issues, but I was discouraged and I didn’t want to go against the wishes of family members.”

In selecting photographs, Cumming looked for images that would be meaningful. “Most people tend to have pictures of how they look all dressed up standing around the Christmas tree,” she said. “…I want a picture of you on your Cat (bulldozer) plowing the ground to plant potatoes — doing something, pictures of you on your fishing boat hauling your net in.”

Cumming said the stories in “And Some Stayed On” could be told in other contexts — for example, the history of commercial fishing in Kachemak Bay, the role of women in homesteading and the history of World War II veterans in Homer’s settlement.

“I see the book as a source of information for making small or larger, quick-to-get-together exhibits at a museum, especially the Pratt Museum,” she writes in her preface, “or as the source of information for school children assigned to giving a talk on their great-grandparents; for a newspaper writer looking for a short biographical sketch; or just as a book for a person who wants to enjoy reading about the way people use to live here.”

O’Meara said she thinks people will be pleased with how “And Some Stayed On” looks.

“I think it looks gorgeous, inside and out,” she said. “I think people who are in it are going to be really happy.”