Dawn of the Daylight Kid

The day before James Edward Hill left Anchorage for Seldovia to begin his stint as a deputy marshal, the Anchorage Daily Times published a notice about his move. Befitting his new rank and important duties, the newspaper said it would no longer be referring to him by his various nicknames. Henceforth, he would be simply U.S. Deputy Marshal James Hill. Period.

Prior to Times article on May 6, 1922, Hill had frequently been called Jimmy or Jimmie and sometimes “The Daylight Kid.”

Probably one of the earliest references to Hill as the Daylight Kid appeared in a sports story in the July 6, 1914, edition of the Valdez Daily Prospector. Hill was an outfielder and occasionally a pitcher for the Valdez baseball team. He was known for his hitting prowess, and in this game he hit three doubles and was hit by a pitch in an 11-4 victory over Cordova.

Baseball was a prime summer entertainment in many Alaska coastal communities, and steamships often offered bargain rates to teams traveling for games. It was a point of civic pride to defeat the teams of rival towns or those cobbled together by cable operators or some other group of working professionals.

Local fans and newspapers became enamored of their players, particularly when their teams defeated squads from towns considered economic foes — such as the competing railroad towns of Seward and Anchorage. Nicknames were frequently bestowed upon favorite players, much in the same way that miners and other characters of the gold rush days had been granted intriguing cognomens.

Hill’s nickname likely came from an ability to “hit ’em where they ain’t,” in other words, to bat a baseball into the open spaces between fielders — finding a little daylight, so to speak.

By 1920, an Anchorage Daily Times notice about Hill’s work as a telephone lineman in the Matanuska District stated that Hill was “known all over Alaska” as the Daylight Kid.

Of course, by this time the “Kid” was 34 years old and had served in the U.S. Army Signal Corps during World War I. A year later he became a married man and was about to apply for a deputy marshal position.

When James Hill and his pregnant wife boarded the launch Sea Lion, bound for Seldovia, on May 7, 1922, newspaper readers were still being reminded that Marshal Hill and the Daylight Kid were one. And the same was true after he was shot dead on the job two and a half years later.

Cleaning up the Town

From the beginning of his time in Seldovia, Marshal Hill was earnest in his efforts to uphold the law. After a man was slain during his first month on the job, Hill arrested the alleged killer and escorted him, via steamship, from the Seldovia jail to Anchorage where the accused man was to face a grand jury. A week later, he made a public plea for aid for the handicapped widow of the dead man.

The Constitutional amendment prohibiting the sale and manufacture of alcohol had been instituted in early 1920, and part of Hill’s job in Seldovia involved seeking out and quashing all bootlegging operations — essentially liquor stills tucked away in the area’s plentiful brush and spruce forests.

Hill made numerous arrests. He destroyed hidden booze and dismantled liquor-making apparatus. One news story claimed that the marshal, along with a Special Prohibition Officer named Flannigan, had “cleaned up the town.”

Certainly, Hill himself was eager to paint a rosy picture of the place. He promoted the booming Seldovia economy — salmon and herring fishing, canneries, a new saltery, fox farming, and new construction.

In a July 23, 1923, article in the Anchorage Daily Times, Hill acted as town booster: “Mr. Hill says times were never better in Seldovia; that everyone is working and the moral atmosphere ideal, there being no law infractions…. ‘The outlook was never better,’ [said Hill].”

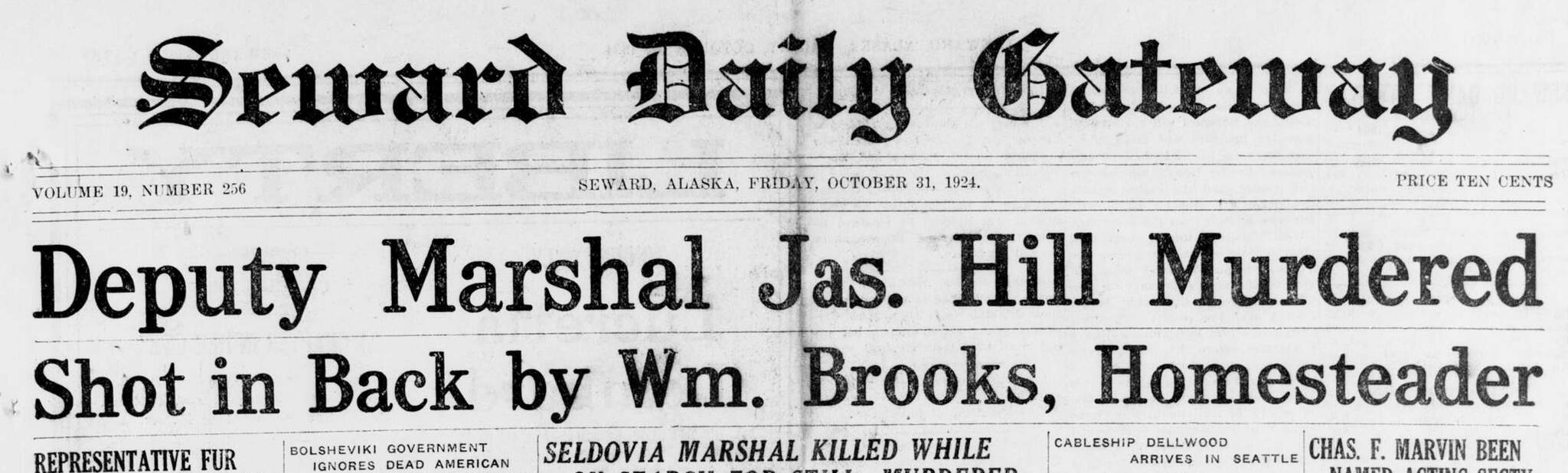

But all that positivity vanished on the day before Halloween 1924.

Fatal Confrontation

Robert Jacobson, a roustabout at the Seldovia jail and the only witness to the killing on that Oct. 30, submitted to investigators an affidavit concerning the tragic event. He said that he and Marshal Hill, along with jailer Milo Hurlburt, had headed to the homestead of William Brooks to search for evidence related to the suspicion that Brooks, along with some other men, were running an illegal still.

The 52-year-old Brooks and his wife Dora had acquired the Mickie Doyle homestead — near the current site of the city airport — after Doyle and his wife moved out of state. Their property lay across the Seldovia slough from the main part of town.

Near a creek on Brooks’s place, the lawmen encountered a canvas wall tent, with two men standing outside and one man inside. After Hill entered the tent to search, Brooks himself wandered up from his house and approached the scene.

Inside, Hill discovered a hydrometer used for testing mash, three empty or partly empty barrels, a gallon jug, a pint bottle with some liquor in it, a siphon hose smelling of liquor, and several funnels. The officers placed the three men in and near the tent under arrest, and Marshal Hill ordered Hurlburt to escort the prisoners to the jail while he and Jacobson continued to search the premises.

Before the search resumed, Hill questioned Brooks about his involvement. Brooks became angry and uncooperative; he then turned away and headed home down a woodland trail.

Marshal Hill told Jacobson that they needed to search the surrounding area for the still he assumed must be nearby. He ordered Jacobson to head upstream and search both sides of the creek, while he did the same heading downstream.

They met up again about 30 minutes later, with neither man having found any sign of a still in the heavy brush. They reentered the canvas tent, and, said Jacobson, the marshal picked up a cup and was about to pour himself some water when Brooks’s “little black dog” bit Hill on the hand.

“Jim chased the dog outside and pulled out a [pistol], emptying it at the dog as it ran down the trail” toward the Brooks home. Hill then turned to Jacobson and said, “I think Brooks is in with the bootlegging gang.”

Down at the Brooks house, meanwhile — according to a written affidavit from Dora Brooks — the intensity of the situation escalated quickly.

Referring to her husband by his last name, Dora Brooks testified: “Brooks came into the house…. We then heard shots coming from the direction of the tent and heard the dog yelp. Brooks said, ‘If [the marshal] has killed that dog, I will kill him.’

“He went in another room and got his rifle and I told him he had better not go up there,” Dora Brooks continued. “He went out of the house and did not answer me. After he got out of the gate he ran up the road and I heard five or six shots.”

TO BE CONTINUED….