“How incredible would it be to have a cabin right there?” I asked no one in particular, pointing vaguely to a rocky beach from the back of a boat motoring through Chinitna Bay.

It was early May, and I’d managed to snag a spot on one of the Kachemak Bay Shorebird Festival’s more exclusive excursions — a day trip to Lake Clark National Park to look for bears and birds.

Even after living in Alaska for nearly three years, it seems like every week I find something new to ogle at. As we glided past tiny coves, protected by an endless expanse of spruce trees and nestled below towering mountains, I had to know: Was anyone lucky enough to live in Lake Clark National Park?

Google helpfully supplied “yes.”

Richard Proenneke first visited Twin Lakes, located in the park on the west side of Cook Inlet, in 1962, according to the National Park Service. After deciding to establish a dwelling in the late 1960s, Proenneke ended up settling on a chunk of land on Upper Twin Lake, near Hope Creek.

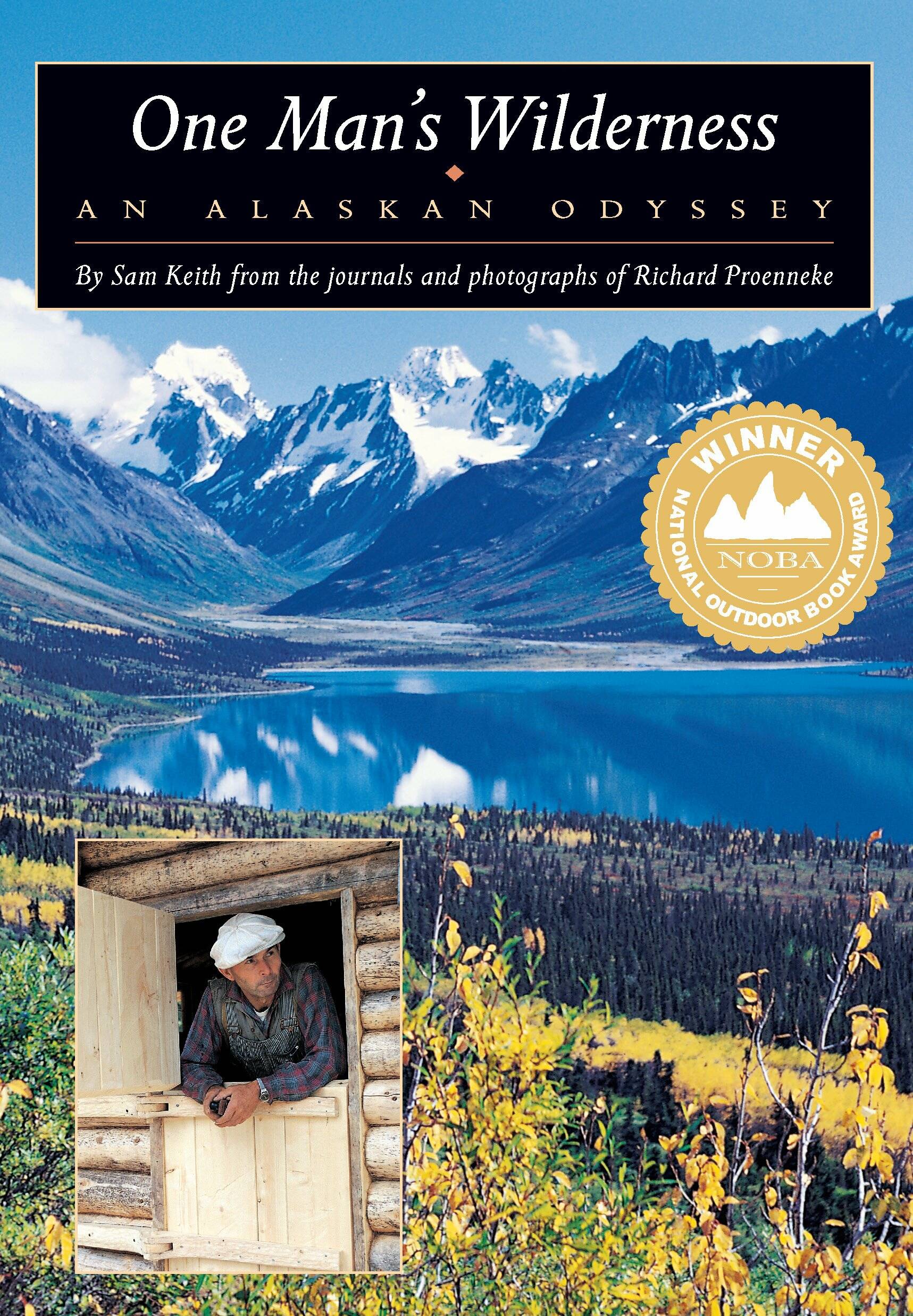

What resulted from Proenneke’s retreat into the wilderness, in addition to his rustic and picturesque lakefront log cabin, was a meticulous series of journal entries compiled and published in 1973 as “One Man’s Wilderness: An Alaskan Odyssey” by Sam Keith.

Keith, a longtime friend of Proenneke, writes in a preface to the book that he was long impressed by Proenneke’s “quiet efficiency” and determination to consistently push his body to its limits. In gathering the snippets of notes and entries left behind, Keith says he attempts to “get into his mind” and reveal the “‘flavor’ of the man.”

“This is my tribute to him, a celebration of his being in tune with his surroundings and what did alone with simple tools and ingenuity in carving his masterpiece out of the beyond,” Keith writes.

With an introduction like that, I wasn’t sure what to expect from the pages that followed. It certainly wasn’t what I got.

“One Man’s Wilderness” reads less like the oft-told man-takes-on-Alaska-wilderness epic and more like a whimsical ticker tape of dispatches from the best of what the Last Frontier has to offer.

“The sun shining on the green lake ice was so beautiful I had to stop work now and then just to look at it,” he writes in a May 26 entry.

“The fog last night froze on the mountains, giving them a light gray appearance,” reads another entry. “That loon calling out of the vapor sounds like the spirit of Edgar Allan Poe.”

There is a youthful exuberance to the tone of the entries that is a refreshing reminder of how magnificent Alaska can be to those for whom the novelty has not worn off.

The book’s longest chapter is a fastidious series of entries describing how Proenneke built his cabin, which has since been added to the National Register of Historic Places and is overseen by the National Park Service. Across 72 pages, Proenneke offers a blow-by-blow, sometimes literally, description of how every log, hinge and piece of furniture was built.

For the carpentry-inclined, these are surely the most riveting pages.

Setting aside the faceoffs with a grizzly bear, the herculean feat of paddling big game against the wind in a canoe, and painstakingly selecting each rock to be placed in his cabin’s fireplace, what I found most compelling about “One Man’s Wilderness” was the Proenneke’s affable and endearing voice and sense of self.

There’s something familiar — I suspect especially for Alaska transplants — about the reverence in which Proenneke holds the splendor of Alaska. It may not be possible to move to Lake Clark in the way I sometimes daydream about, or the way Proenneke actually did, but there’s enough character in his snippets of bush life that “One Man’s Wilderness” is an OK consolation.

Off the Shelf is a bimonthly literature column written by the staff of the Peninsula Clarion.