Something I often find myself commenting on when people ask me about living and working in Alaska is how young this place feels.

Every now and then I’ll talk to someone who’s lived here since before Alaska was a state, or who were friends with people who were delegates to the Alaska Constitutional Convention, and suddenly “history” feels less like something that’s already happened and more like something Alaskans are still, in this moment, building together.

While that’s somewhat true, that understanding of history refers only to the trappings of statehood. The wildness of Alaska has always existed — before it was called “Alaska” — and Indigenous people have for thousands of years stewarded the land.

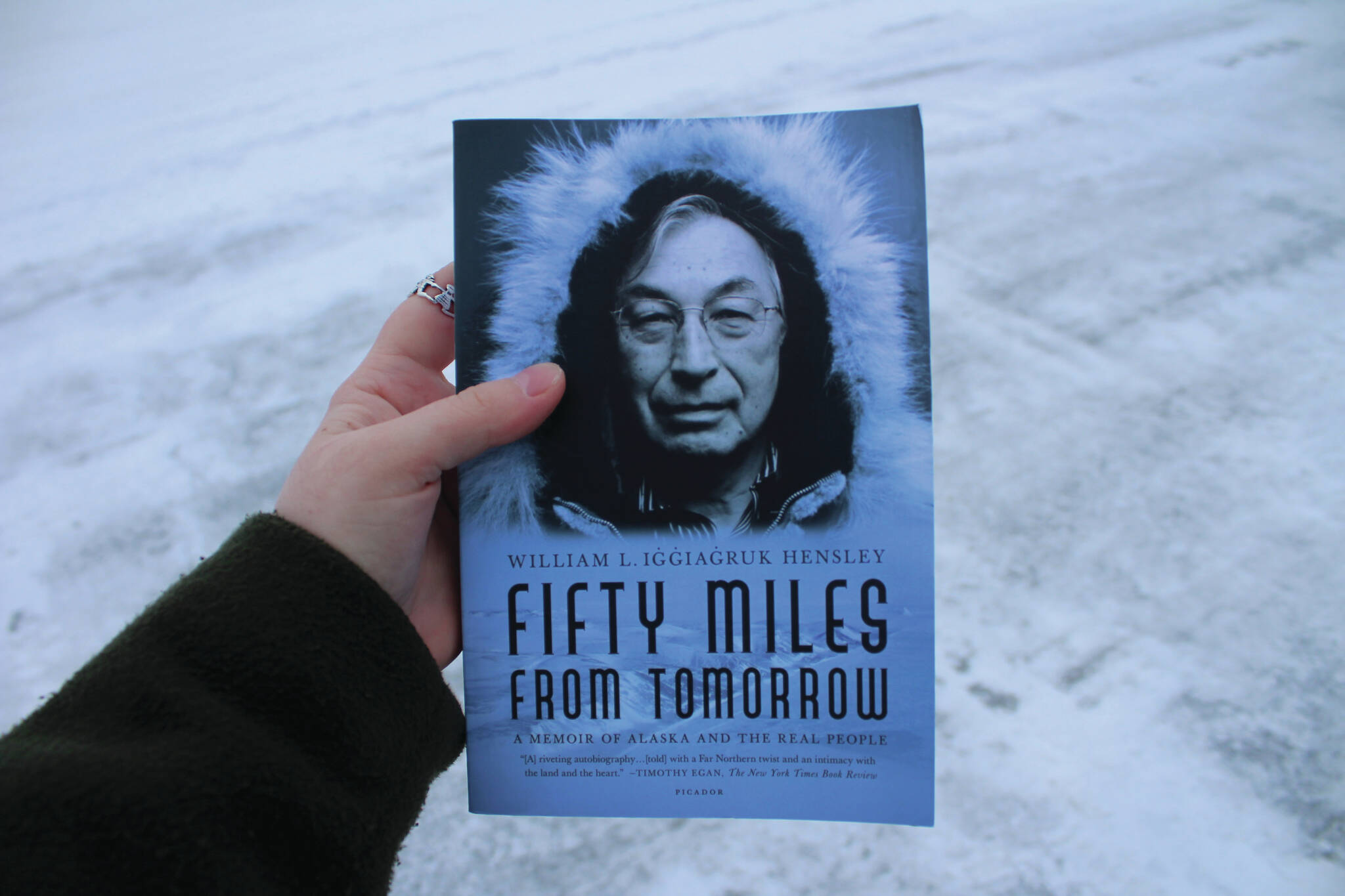

In “Fifty Miles From Tomorrow,” William L. Hensley, who also uses his Iñupiaq name, Iġġiaġruk, divulges a lifetime worth of insight into both his childhood in the northwest Arctic and his decades of service as an unwavering champion of Alaska Native rights on the state, national and international stages.

“Fifty Miles From Tomorrow” is as much a love letter to Alaska’s Iñupiaq and other Arctic people as it is a thrilling account of someone who was on the front lines of landmark decisions in the history of rights for Alaska Natives. He outlines the origins of his life of activism, which he says were sparked by an essay he wrote as a student at the University of Alaska Fairbanks.

“The United States had never won any land from Alaskan Natives in battle,” he says. “It had never signed any treaties with the Alaskan Natives. Legal precedent was clear: if land not been taken in battle or seized by an act of Congress, the federal courts had consistently found that Native Americans retained ‘aboriginal title’ to it. That had to mean that we still owned most of Alaska!”

It is difficult to succinctly summarize Henley’s contributions to Alaska, but I’m going to try. He’s a former Alaska State representative and two-time state senator, a founder of the Northwest Alaska Native Association and helped establish the Alaska Federation of Natives. His work helped create and pass the Alaska Native Claims Settlement Act of 1971, which transferred 44 million acres of land and titles to Alaska Native regional and village corporations.

As a lawmaker, he fought laws that said Alaska Native people could not be cared for at Pioneer Homes, helped established Kotzebue’s first public radio station, helped build three new high schools in his district to prevent students from having to move away to school and fought for revenue from liquor store sales to stay in the communities where the store was located.

Hensley speaks candidly about his experience in government-run schools where, he says, “it was as if our people did not exist.” He talks about what it was like to find out his family had been forced from their home after being subject to a foreign system of private land ownership. He lays bare all the ways Alaska Natives were written out of, or generally not considered, as Alaska grappled with the implications of statehood.

“At this point in our history, our own leaders were not about to take on both the state and federal governments and the powerful business interests that were so avidly eyeing Alaska’s riches—riches that very likely lay in our traditional lands,” he writes of his decision to run for State House in 1966.

He clearly outlines the various factors that converged to help get ANCSA passed. The legal fight for Alaska Native claims to land stalled work on the trans-Alaska pipeline, which helped rally the business community behind the cause. President Richard Nixon was hoping to replicate the favorability that came with championing similar causes. Native groups had the U.S. Interior secretary on their side.

Present on every page is a tangible reverence for Hensley’s roots in Kotzebue and the Arctic. With that, though, comes the anger Hensley says he carries about the way his people have been treated. A particularly compelling chapter is “Puttuqsriruŋa: Epiphany in Nome,” in which Hensley describes feeling listless and demoralized even in the face of significant accomplishments.

“For the first time, I suddenly recognized the full extent of the human suffering that had been taking place among our people in the least obvious of places: in our minds and spirits,” he writes. “For the first time, I truly began to understand some profound truths about the nature of identity, culture and connection and about the systematic measures … used by nations all over the world to destroy the spirit of the minorities within their borders.”

A key theme of “Fifty Miles From Tomorrow” is Hensley’s mission to preserve the history and culture of Alaska’s Indigenous communities, and it is fitting that the act of reading his book puts readers in the position of participating in that preservation.

“Fifty Miles From Tomorrow” opens with an essay about Iñupiaq writing and pronunciation, that was written by Lawrence Kaplan — a professor emeritus at the University of Alaska Fairbanks and the former director of the Alaska Native Language Center.

The essay is complemented with a glossary included at the end of the book; I found myself regularly consulting both. The title of each chapter is written in both Iñupiaq and English, and the chapters themselves are peppered with Iñupiaq vocabulary.

Hensley’s writing is raw and riveting and shows in equal parts his humor and great capacity for caring, but also his commitment to his convictions and dedication to fighting for what’s right. He straddles the threshold of where traditional Arctic ways meets the contemporary configuration of Alaska as a state.

It’s a can’t-miss read for all who want to better understand the forces behind the iteration of Alaska we live in today. After one read, my copy is dog-eared and annotated, and will have a permanent home in my desk at work.

“Fifty Miles From Tomorrow” was published in 2009 by Picador.

Reach reporter Ashlyn O’Hara at ashlyn.ohara@peninsulaclarion.com.

Off the Shelf is a bimonthly literature column written by the staff of the Peninsula Clarion.