Amplifying stories written by and about Black Americans is one of the best ways to close out Black History Month, in my opinion. Fortunately there are so many great ones to choose from, but one I read last month sticks out.

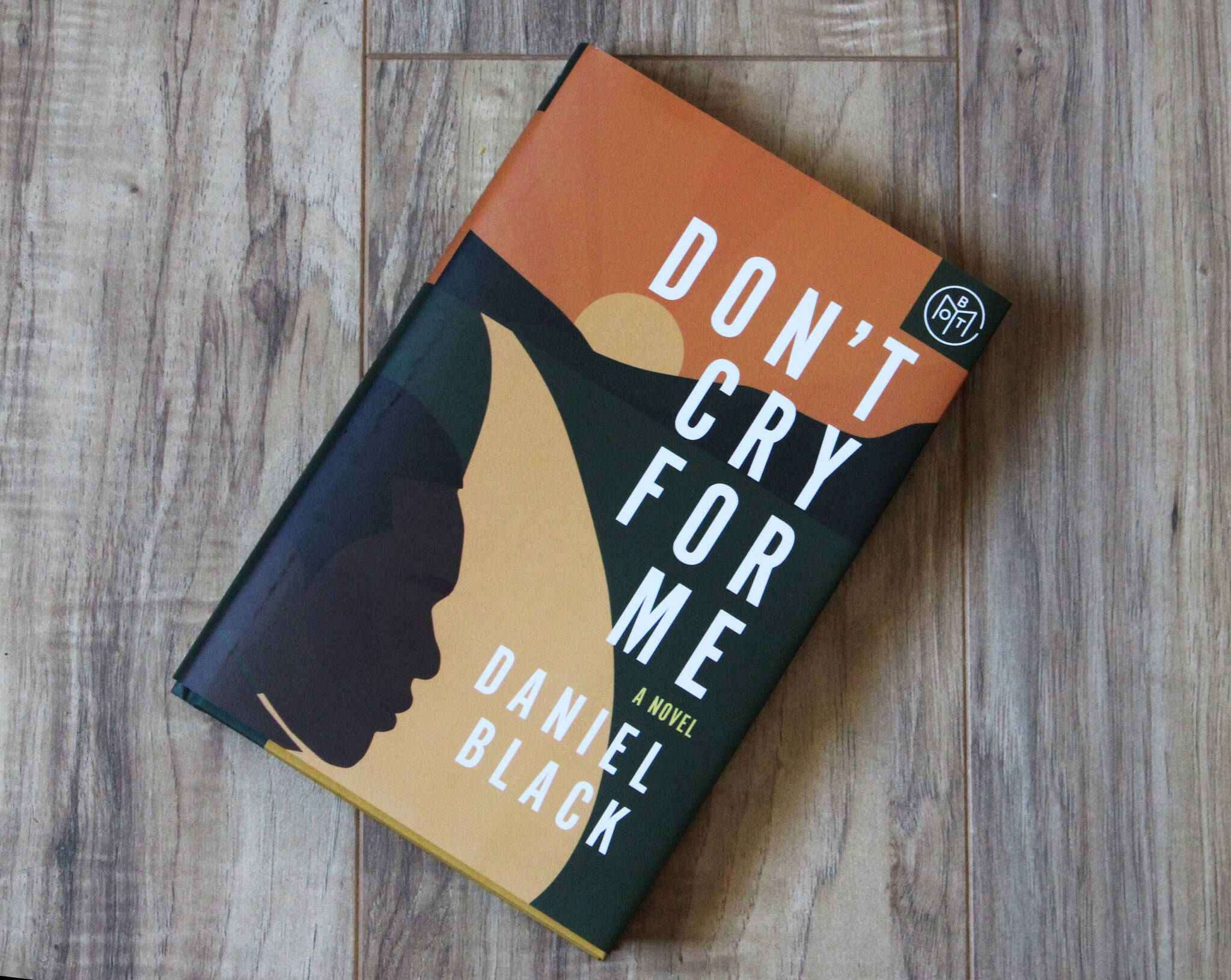

Daniel Black’s latest novel “Don’t Cry for Me” tells a raw and reflective story of a father, Jacob, and estranged son, Isaac, through letters penned from Jacob’s deathbed. Haunting and heartfelt, Jacob’s letters reflect on he and Isaac’s turbulent relationship and his efforts to make sense of his own upbringing.

Black writes in an introductory note to readers that Jacob’s letters represent the type of reconciliation he wishes he could have reached with his own father. Necessary to achieving resolution, he writes, is a shared understanding of the environment fathers were raised in and how that environment shaped a certain image of manhood that is passed from fathers to sons.

“This book, this record of a poor black father’s appeal, is what any dying daddy might say to his son,” Black writes. “More than anything, I want readers to reconsider the capacity of our fathers’ hearts. Many of them were handled so little, yet we expected so much.”

A central motif and source of conflict across the book’s 300 pages is the idea of masculinity and how that idea is or is not upheld by characters. Jacob’s understanding of how men, particularly Black men, should behave, he writes, comes from the stoic and hardworking disposition of his grandparents, who raised him.

Yet, it is that understanding that works to fracture his relationship with Isaac, who is gay and doesn’t behave in a way that Jacob understands. There’s a persistent effort to reconcile the son he’s created with an inherited legacy of masculinity Jacob describes as “power” “influence” and “godliness.”

“Boys don’t kiss other boys in my house!” Jacob says when he sees Isaac making two action figures kiss. “Men don’t do that! Women do that!” he yells at the way Isaac cleans his mouth with a napkin. Jacob says he equates queerness with femininity and sees his sons sexuality as running counter to tenets of masculinity.

Contributing to Jacob’s struggle to accept Isaac is what Jacob calls a set of rules that come with being black that he says Isaac disregards. Jacob at one point describes a white woman wearing a shirt that says “My daughter is a lesbian because she’s supposed to be” and wonders at how a parent could be proud of having a queer child.

“Maybe things were different for white folks,” Jacob says. “Perhaps they enjoyed the privilege to be whatever they wanted. But black folks had rules and restrictions we were supposed to abide by.”

For all of Jacob’s flaws, however, Daniel Black makes redemption possible. Jacob picks up a love for literature, which empowers him to reevaluate his sense of self. Finishing Alice Walker’s “The Color Purple” ignites the beginnings of reconciliation between Jacob and his wife, from whom he is divorced, and gives him new insight into the relationship between his own mother and his grandfather.

“I’d never thought of what it meant for a woman to live in perpetual fear of a man,” he writes.

Still, he does not attempt to negate the damage that has strained his and Isaac’s relationship. He is candid about his expectations and asks only that Isaac use his letters to reevaluate their relationship with Jacob’s experiences in mind.

“There are no do-overs in this life,” Jacob writes to Isaac. “Either you get it right or you wish you had.”

“Don’t Cry for Me” was published on Feb. 1, 2022, by Hanover Square Press.

Ashlyn O’Hara can be reached at ashlyn.ohara@peninsulaclarion.com.

Off the Shelf is a bimonthly literature column written by the staff of The Peninsula Clarion that features reviews and recommendations of books and other texts through a contemporary lens.