One of my favorite internet memes is a screenshot from the show “Arrested Development.”

In the scene, character Lucille Bluth who, while holding a cupcake and expressing resolve, says “good for her” after listening to a news story about a woman who drives her car into a lake after saying she could “take it no more.”

Some people use the meme in response to instances where repressed feminine rage is realized, but I find myself saying “good for her” in almost every instance where a woman gets the last laugh after being treated badly.

Think of the character Nora Helmer in Henrik Ibsen’s 1879 play, “A Doll’s House,” or of Amy Dunne, who frames her husband for murder in Gillian Flynn’s “Gone Girl.”

“He took and took from me until I no longer existed,” Dunne says of her husband. “That’s murder.”

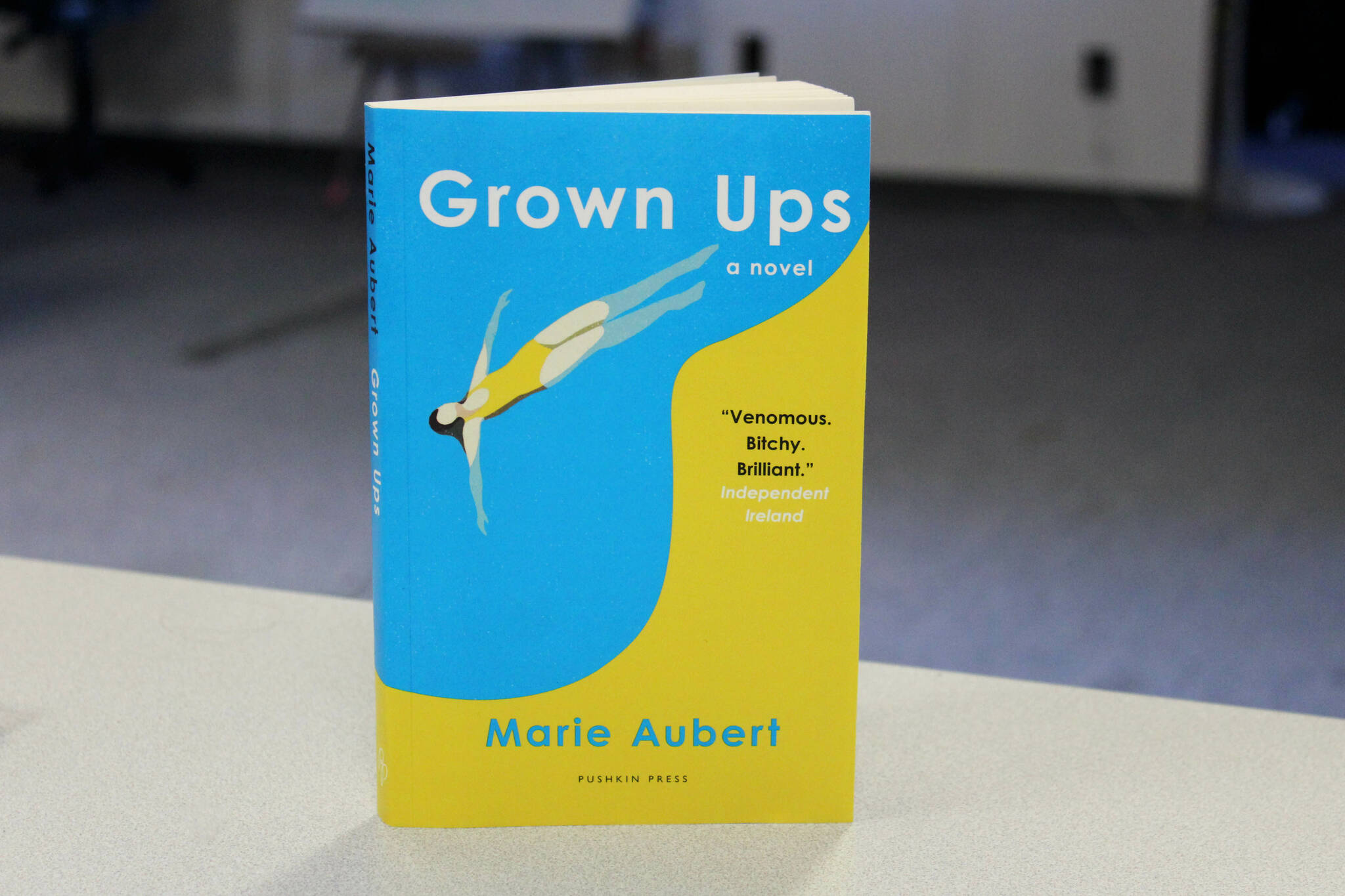

As women’s history month kicked off on March 1, I found myself craving more stories with a “good for her” trope. That’s how I ended up with a copy of Marie Aubert’s “Grown Ups,” which caught my attention with a flashy cover and a review from Independent Ireland on the cover: “Venomous. Bitchy. Brilliant.”

The short and breezy novel follows Ida, a woman in her 40s who is going through the process of freezing her eggs ahead of a vacation with her mom and sister’s family at their shared vacation home. Ida resents her sister, Marthe, for being needy and wanting attention, but quietly revels in petty triumphs that she fails to see are equally immature.

“It’s so tempting, it does Marthe good to be given a kick up the bum every now and then, and it’s so nice to wink at Olea, to make her giggle and watch as her eyes grow wide with glee at how funny I am,” Ida says

Ida doesn’t perfectly fit the “good for her” trope. She’s messy and makes bad decisions and more than once lets sibling jealousy get the better of her in a way that makes it hard to feel bad for her. Still, there’s a quiet anguish palpable across the book’s 150-some pages that is reinforced each time we see her wants take a back seat to her sister’s neediness or her good intentions run astray.

The novel is largely anticlimactic, but it culminates in a satisfying way that sees her moving out of the childhood bedroom to which she’s been relegated, overcoming the childish antics holding her back and putting her own desires first.

“I move my things out of the tiny bedroom and into the large one,” Aubert writes. “Then I go out onto the decking and look out at the fjord. It’s only me here. I stand there in silence and feel the sun on my face.”

Do I think Ida is a particularly compelling or likable character? No. Still, as I read that final line, I found myself saying “good for her.”

“Grown Ups” was first published in 2019 as “Voksne Mennesker” by Forlaget in Norway and as “Grown Ups” in 2021 by Pushkin Press.

Reach reporter Ashlyn O’Hara at ashlyn.ohara@peninsulaclarion.com.