A journalist I admire once said that she reads a lot of short stories, with the goal of better understanding ways to tell compelling narratives with limited space and time. A lot of great journalism, she said, does the same thing.

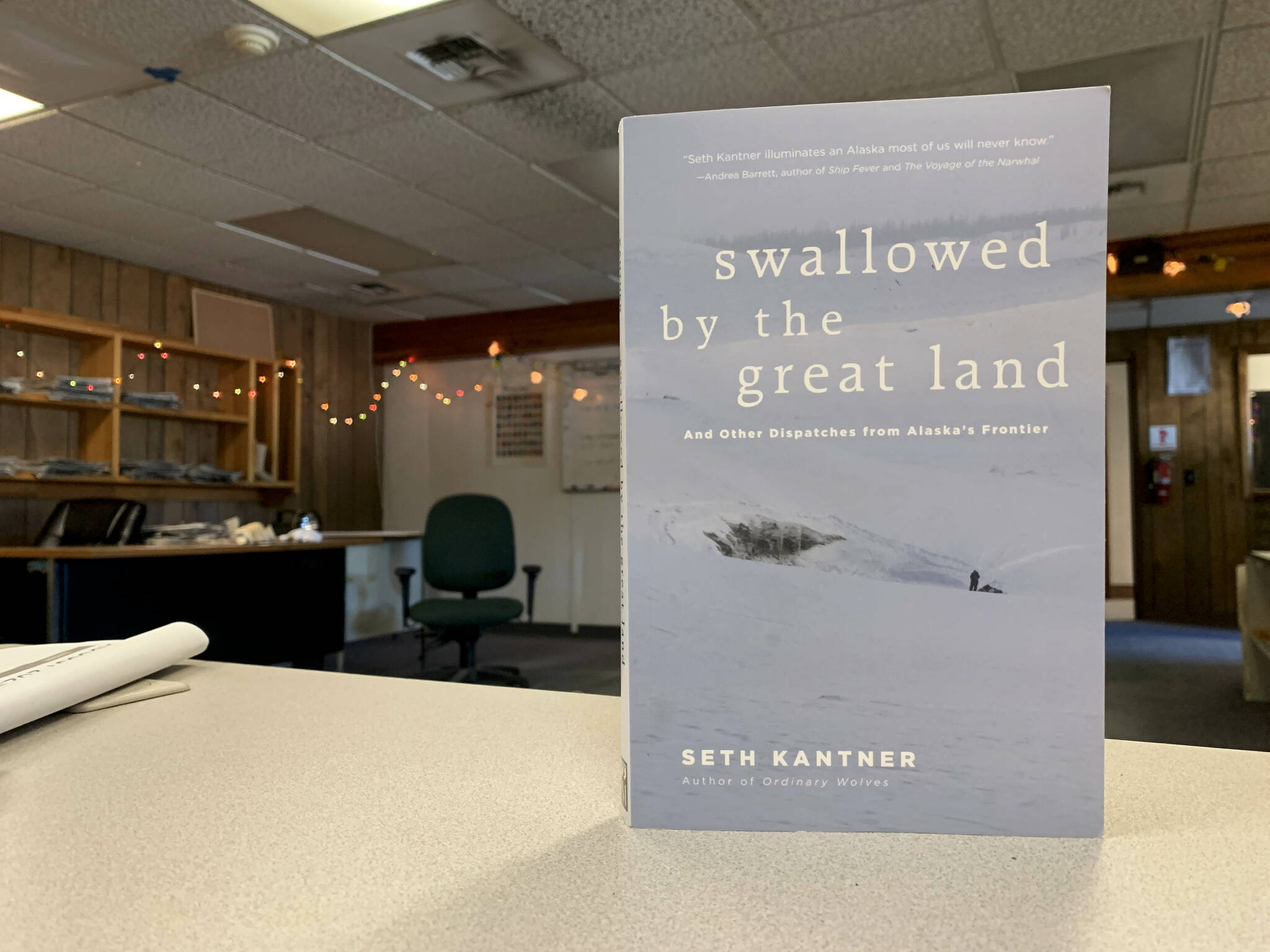

It’s with that idea in mind that I purchased a copy of Seth Kantner’s 2015 “Swallowed by the Great Land: And Other Dispatches From Alaska’s Frontier.” I was already familiar with Kantner because of the hype around “A Thousand Trails Home: Living with Caribou,” which was published in 2021, but have not read any of his other work.

I’m sure “Swallowed by the Great Land” will change that.

“Swallowed by the Great Land” is divided into five sections, each thematically focused on a different aspect of life in the Arctic. They cover, in order, home and day-to-day life, people, subsistence, the cold. The stories in the book’s final chapter, “storm clouds” talk about how the Arctic way of life is being threatened, from climate change, to development, to gun violence.

It didn’t shock me to read on the book’s “About the Author” page that Kantner received a bachelor’s degree in journalism from the University of Montana. Each of the 50 stories in the collection has a good balance of information and narrative, and many sentences read more like poetry than prose.

“The sun is to the north, scallops of snow in the mountains,” he writes in one chapter. “The hollows in the tundra and the trees and the last snowdrifts beside our feet are refilling with evening light like cups of gold.”

Still, the stories are not without an element of foreboding. Kantner worries about what a changing climate and pro-development politics mean for him and the other Arctic dwellers.

“All the climate change talk these days puts you on edge and depletes your trust and confidence. Each new cave-in along the river — is that permafrost melting? … For those of us who have lived lives closely tied to the land, these are extra-confusing times.”

In what I’d now call one of my favorite books written by an Alaskan, about Alaska, Kantner offers a quiet, earnest, lovely window into his unique life as someone born and raised in Kotzebue. A throughline of the book is the sense that Kantner, who describes himself as shy and someone who doesn’t enjoy “pestering people,” is being vulnerable by allowing readers a peek into his life.

Through “Swallowed by the Great Land,” we meet his family, know his friends, learn Iñupiaq vocabulary and Iñupiat traditions picked up by Kantner over the course of his lifetime, and are told the sad story of his “thirdhand dog.”

Like the best stories about small towns, the reverence Kantner has for his community and way of life is one you can’t help but envy. There’s something satisfying about knowing that someone is where they should be and doing what they should be doing; I get the sense that is true of Kantner.

“The snow was deep, all of us deep in winter,” reads one line. “No one we knew was in a hurry. Time, and tundra, we had in unlimited supply.”

Reach reporter Ashlyn O’Hara at ashlyn.ohara@peninsulaclarion.com.

Off the Shelf is a bimonthly literature column written by the staff of the Peninsula Clarion.