I’m going to start this column out by acknowledging that I can be a bit of a hippie when it comes to animals. Maybe it’s because I grew up watching so many movies with anthropomorphized animals — I’m looking at you, “Bambi” — but there’s something about a creature incapable of malice that makes my heart feel especially tender.

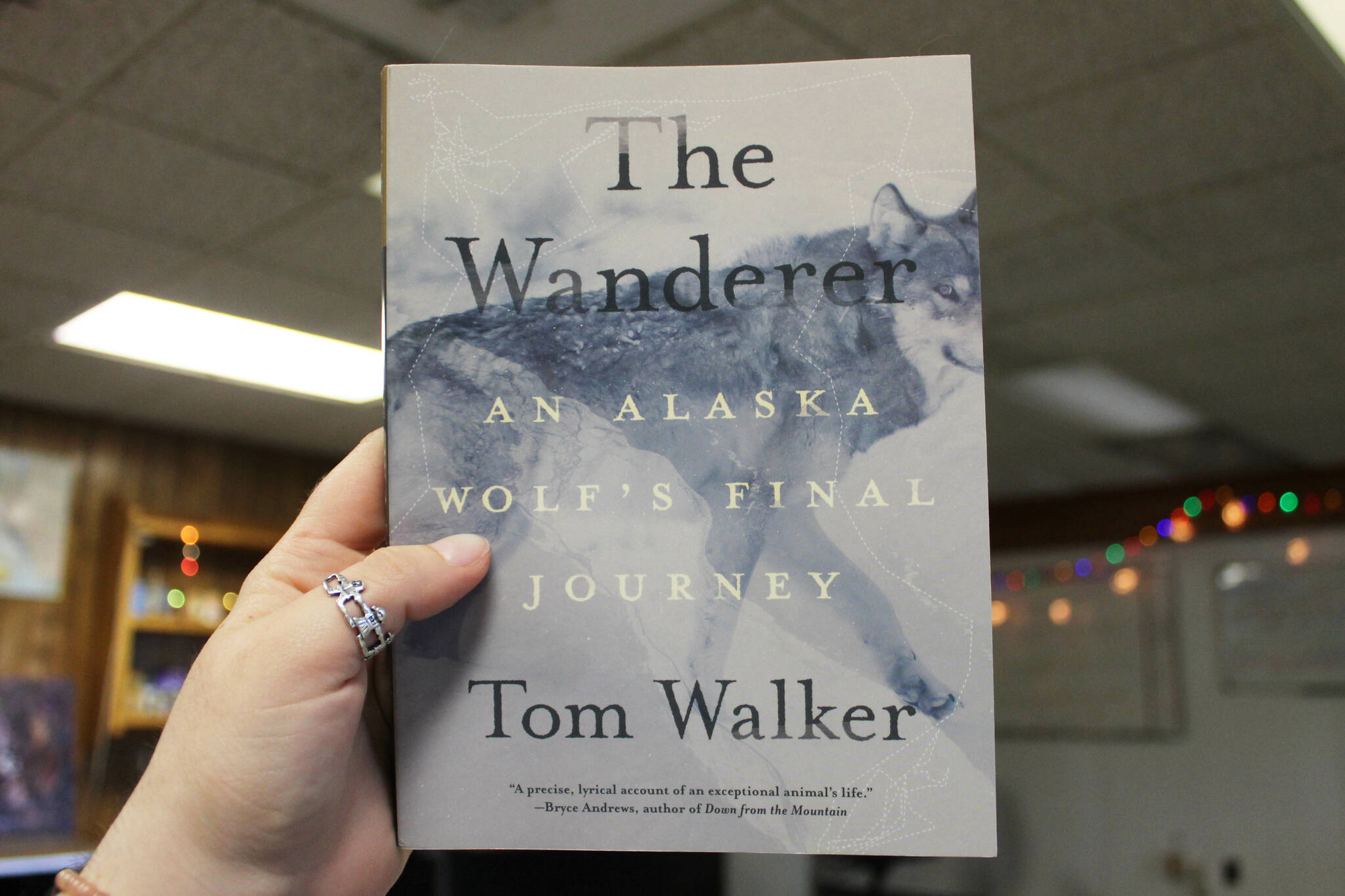

It’s with that affinity for fauna that I found myself drawn to a book at Title Wave in Anchorage last month. The cover shows a fierce-looking wolf trotting through snow and a back cover that promised revealing insights into the behavior of an extraordinary Alaska canine.

“The Wanderer: An Alaska Wolf’s Final Journey,” is the latest book from Alaska writer and photographer Tom Walker, and follows Wolf 258, dubbed “The Wanderer,” on a nearly 3,000-mile trek through interior Alaska. Across roughly 170 pages, Walker uses the Wanderer’s impressive GPS footprint as a segue into larger topics like climate change and conservation policies.

The book is filled with helpful, concise passages on bits of Alaska history key to understanding the geopolitics at play in the interior, such as the Alaska National Interest Lands Conservation Act, the significance of the Porcupine caribou herd to Alaska Natives, the Alaska Native Claims Settlement Act, namesakes of significant interior landmarks and state management of predator populations.

Throughout, Walker challenges the image of the Alaska wolf as a bloodthirsty predator whose free reign is causing a decline in caribou populations. Rather, he puts forth the idea that wolves, like caribou, are products of their environment, which is rapidly changing due to global warming.

There are compelling scenes, for example, of how extended warm temperatures are abetting an abundance of mosquitoes — “the biomass of mosquitoes on the North Slope alone is said to be larger than that of all Arctic caribou combined.” In addition to being a nuisance, the insects feed aggressively on wolves and caribou alike, sending each group off of breeding grounds in search of respite.

At the very least, “The Wanderer” presents a trove of information relevant to understanding the kinds of circumstances that threaten the survival of Alaska wolves. For that reason, the book reads just as much like an epic survival story as much as a fact file on one of the Last Frontier’s more elusive predators. Walker is sure to note the irony of one of these predators succumbing to apparent starvation.

The final pages carried, for me, the frantic energy of a thriller novel. As the title indicates, it covers one wolf’s final journey. I was naively rooting for the Wanderer to find a caribou and get some food, but was instead met with his slow decline into death by apparent malnutrition on the banks of the Kanuti River.

“On his side, nose into the wind, he blinked and the world came into focus,” Walker writes. “He could see the spruce needles dark and sharp against the faint sky. A hard gust shook the limbs; he heard the rustle and felt pelting ice. One last breath, and he was still.”

Call me sappy, but that scene is straight out of the saddest Disney movie you’ve ever seen.

A free copy of “The Wanderer: An Alaska Wolf’s Final Journey” was provided to the Peninsula Clarion, however, the copy used for this review was purchased by the column author.

Off the Shelf is a bimonthly literature column written by the staff of the Peninsula Clarion.