As you take time to remember during this Women’s History Month all of the contributions women have made to propel humankind forward, it is equally important to acknowledge those actively working to secure the future of generations yet to be born. One of those living legends is Malala Yousafzi.

A relentless pursuit of equal educational opportunities for girls, Malala is native to northern Pakistan’s Swat Valley and is perhaps best known for being shot at age 15 by the Taliban on her way home from school. Her school was owned and run by her father, who is also an education activist. Prior to being shot, Malala and her father were open advocates for equal access to education for girls in Pakistan.

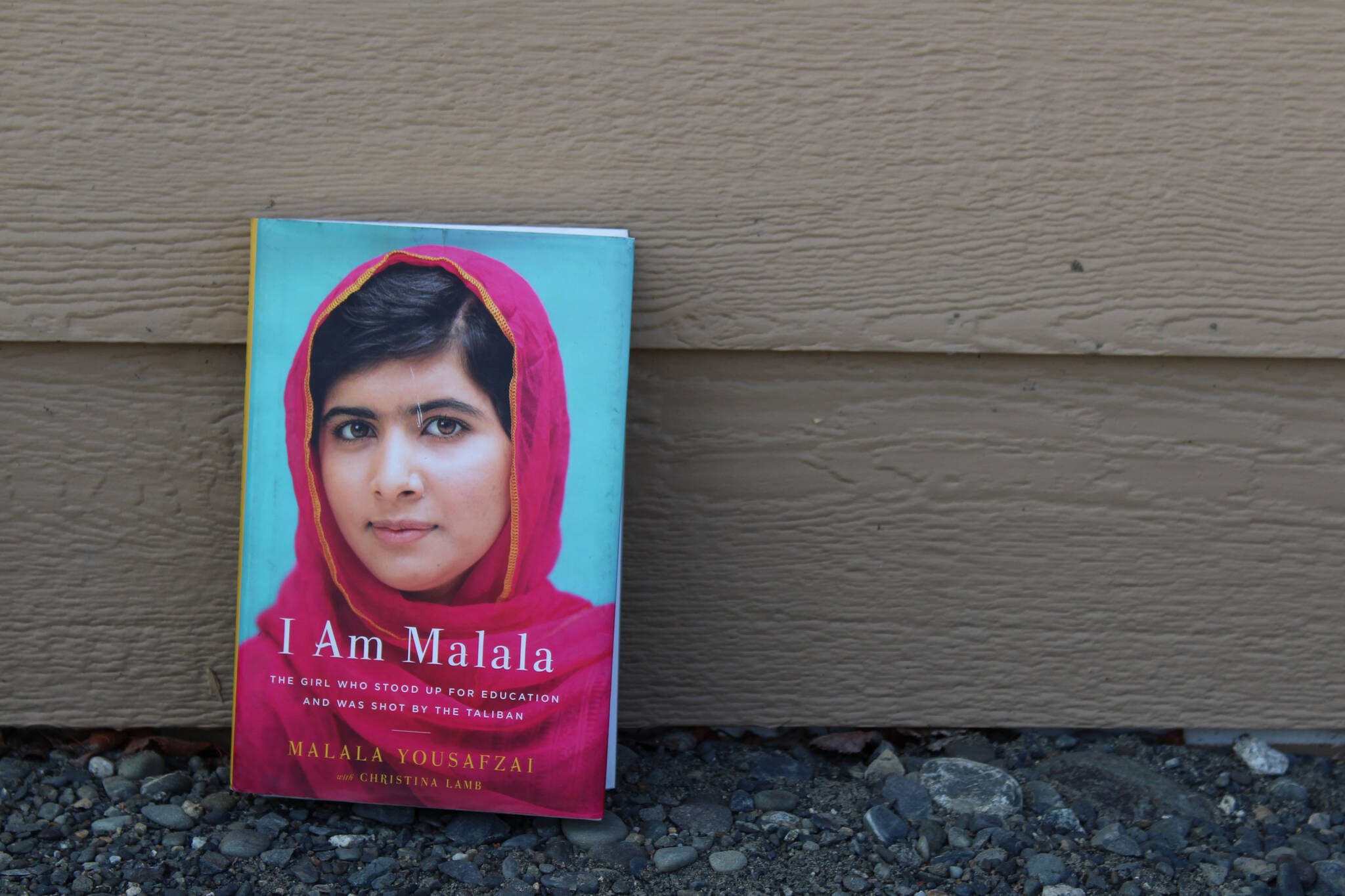

In her 2013 book, “I Am Malala,” which was written by her and Christina Lamb, Malala recounts her youth in Pakistan, her zeal for learning and growing up amid the rise and fall of the Taliban in Pakistan. A comprehensive chronicle of Pakistan’s fight for sovereignty and stability serves as the backdrop to Malala’s own tale of faith and family.

Malala and I are roughly the same age (she’s a bit older), and her story is always one I’ve felt connected to. Like Malala, I am close with my dad, who, along with my mom, has always supported me. My parents are both veterans, and my dad served in the Middle East when I was young. I texted him after I finished Malala’s book and noted the absurdity of her and I growing up at the same time on opposite ends of the conflict.

Yet, our lives could not have been more different.

At the same time I was loading my backpack and walking with friends to school, Malala was “making sure the gate was locked at night and asking God what happens when you die.” She describes the persistent fear that the Taliban would throw acid on her face, as they’ve done to girls in Afghanistan, and the weaponization of the Islamic faith by the Taliban, who would say women who went to school would not go to heaven.

“I am very proud to be a Pashtun, but sometimes I think our code of conduct has a lot to answer for, particularly where the treatment of women is concerned,” Malala writes of the way women are treated generally by people around her.

The Taliban just this week said it would not be allowing girls to attend school beyond sixth grade.

As reported by NPR, most girls and young women have been “prevented” from attending secondary school since the Taliban took power last August. Schools were reported for boys and for girls up to sixth grade, NPR reported, and women could attend college if segregated from male students and if they adhered to a dress code.

It’s a sobering reminder of the freedoms we take for granted in the United States and the importance of the advocacy work people like Malala are doing.

“When someone takes away your pens you realize quite how important education is,” Malala writes in her autobiography.

In one of the book’s closing chapters, Malala describes how getting shot revived her commitment to seek equal access to education for girls. A devout Muslim, she closely ties that mission to her faith and relationship with God.

“A Talib fires three shots at point-blank range at three girls in a van and doesn’t kill any of them. … It feels like this is a second life. People prayed to God to spare me, and I was spared for a reason — to use my life for helping people.”

Malala Yousafzi is a Pakistani advocate for girls’ education. She is a recipient of the Nobel Peace Prize and graduated in 2020 with a degree in philosophy, politics and economics from Oxford University. More information about her story can be found at malala.org.

Ashlyn O’Hara can be reached at ashlyn.ohara@peninsulaclarion.com.

Off the Shelf is a bimonthly literature column written by the staff of The Peninsula Clarion that features reviews and recommendations of books and other texts through a contemporary lens.