I never knew a time when newspapers were successful. Maybe I never will. When I started as a reporter at the Clarion, it was a very small operation — and against all odds it’s managed to grow smaller in the years since. Our story is hardly unique.

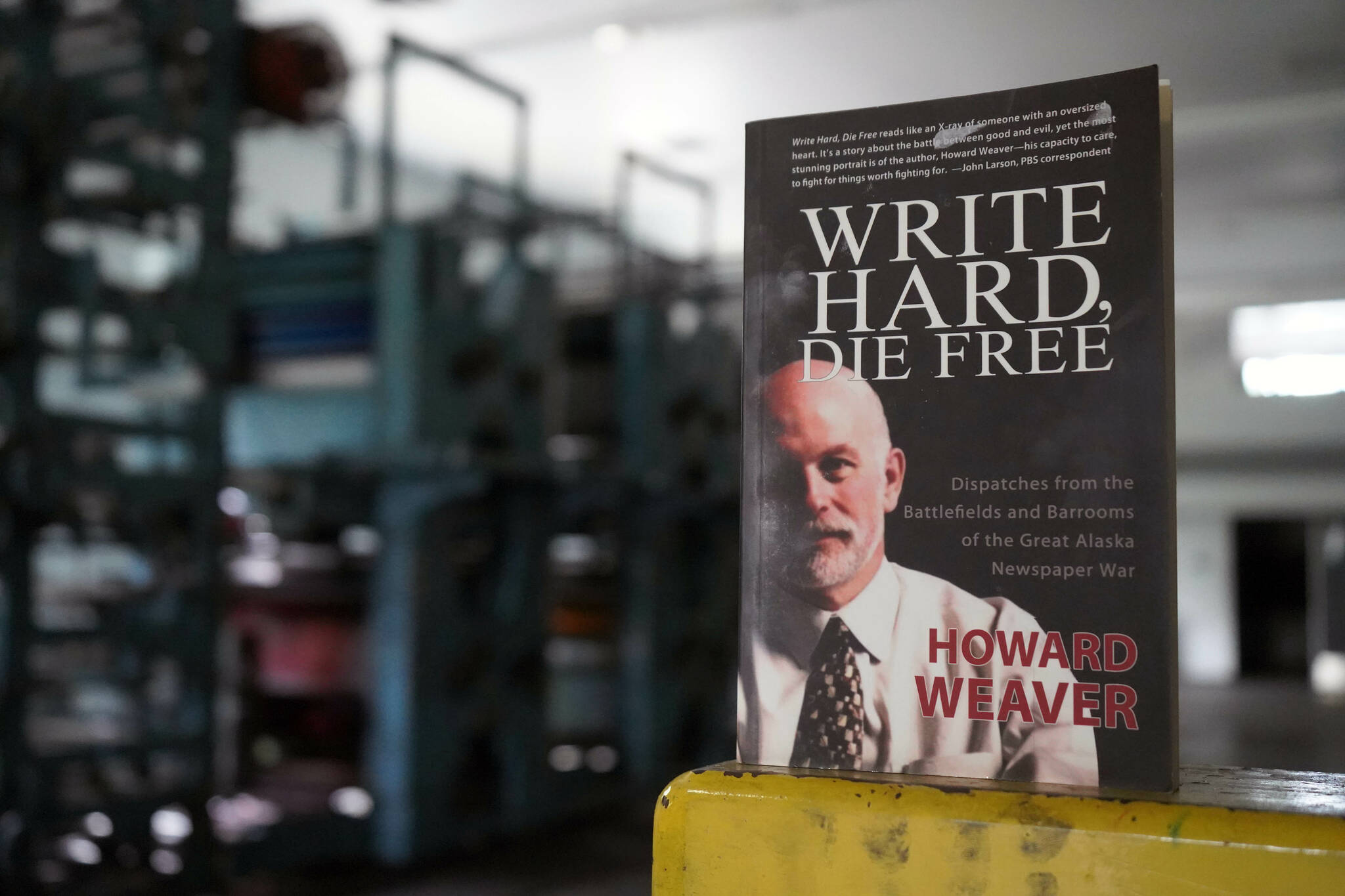

Immediately after the death of legendary Anchorage reporter and editor Howard Weaver, I picked up a copy of his memoir, “Write Hard, Die Free.” I scoffed at its subtitle — “Dispatches from the Battlefields and Barrooms of the Great Alaska Newspaper War.” The text centers on his decades-spanning struggle to see the Anchorage Daily News rise from the shadow of the Anchorage Times and ultimately see its competition wholly eliminated.

It’s not that I can’t imagine a time when newspapers were successful enough to war over subscribers and advertisers — there’s enough empty desks and unused space in the Clarion’s cavernous building to paint a picture of a very different operation not-so-long ago. Instead, the idea of such a war seems almost cynical and antithetical to my views on journalism — I think we need more reporters in Alaska, not fewer. I can’t imagine celebrating the downfall and loss of another outlet, and I’ve already seen another local newspaper fold.

From the first chapters, my derision was proven misplaced. Throughout “Write Hard, Die Free,” Weaver shares anecdotes that sprawl across decades of reporting in Anchorage, mostly at the Anchorage Daily News. He openly confronts his flaws, but endlessly describes his love for and earnest belief in reporting — in an early passage, he fails to argue when his first wife says he loves the newsroom more than her.

In reporting, Weaver writes, he found community and he found purpose — most specifically, “a crusade to create journalism worthy of what Alaska meant to me.”

His “Great Alaska Newspaper War” was a righteous endeavor, he writes, because of failings he perceived in the Times in reporting for the whole community, especially by the end of the war when its owner was part of “Big Oil.”

Before reaching that end, Weaver writes sharply and insightfully, constantly rolling from one story to the next in a depiction of Alaska journalism from before the turn of the century that reads entirely like fantasy.

On one page he’s grappling with the realities of reporting on “someone’s husband,” the next he’s tailing “known associates” of an Arizona crime family through Anchorage. He describes Alaska newsrooms with as many as 90 people in them — a far cry from the Clarion’s three — and an instance where his newspaper bought a boat to cover the Exxon-Valdez spill after failing to acquire a charter.

In one odd aside he mentions and presents evidence of his own preternatural insight into a digital future years before it arrived. The ADN was one of the first newspapers to explore a digital presence in the 1980s. Weaver writes that he regrets not doing more to push forward journalism in the earliest days of a digital revolution that would largely leave newspapers behind.

“Why didn’t I do more about it?” he asks. “That’s a question that troubles me still.”

Repeatedly, Weaver shares his views of what good journalism is and isn’t, he grapples vulnerably with his own failings, and he pontificates on leadership that created strong journalists. Throughout, he maintains that Alaska, specifically, deserves quality reporting that it won’t get from Outside. That means writing with purpose and intention, telling valuable stories and ignoring what’s boring.

I’m a sicko for an overly generous — even naive — perspective on journalism as a service of tremendous value. I think reporting matters, which is why I do it, and I was wholly swept up Weaver’s grandiose ideals for better journalism in Alaska.

“Our dream is to produce a newspaper that truly serves this community without fear and without favor,” he writes.

I was less enamored with his extremely favorable perspective on corporate ownership of newspapers — of course, he did go on to be a vice president at McClatchy. I’ve long thought corporate chains and hedge funds to be the biggest threat to journalism in America, so I had a little trouble stomaching “McClatchy’s corporate support was the singular ingredient without which none of this could have happened.”

“Write Hard, Die Free” is an intricately detailed window into an era of journalism — and Alaska as a whole — long gone. It kept me enthralled and left me fired up, despite concluding on a real dour note where Weaver leaves Alaska with his heartbroken, grappling with the impacts of capitalism on the newsroom he once helmed, facing disillusionment in some of the ideals he once clung to so resolutely.

In its final pages he teases a new understanding of Alaska that he intended to explore in another book, but that doesn’t seem ever to have been published before his death last year. Nevertheless, the excitement I felt as I pored over his idealistic views of what newspapers and more broadly journalists can and should be left an impression, and his stories certainly entertained.

“Write Hard, Die Free” was published by Epicenter Press in 2012.

Reach reporter Jake Dye at jacob.dye@peninsulaclarion.com.