AUTHOR’S NOTE: If I ever write a book on the history of my family’s homestead — and of homesteading in Alaska, in general — this story will be part of an early chapter.

As the 1960s were beginning, Stanley Nelson found himself in an Anchorage hospital, his head bandaged, his health compromised and his spirit of adventure diminished. Shortly after, he relinquished to fate his dream of building a home on the Kenai Peninsula.

I do not know whether his surrender was determined or reluctant. Does anyone like to give up on a dream? But I do know this: Bad luck for Stanley Nelson equaled good luck for the Fairs. We didn’t ask for it, but we clearly profited at his expense.

So, although it may sound callous, I owe Stan a debt of gratitude. Without his misfortune, almost everything changes for me. My touchstones, perhaps much of my character and many of my sensibilities, are altered. So thank you, Mr. Nelson. I wish I knew more about you, even though, truly, your connection to the place I was raised was tenuous and temporary. In the grand scheme of this Fair Family stage play, yours was a bit part. But without you, all the acts change. All the scenes are rewritten. Everyone gets different lines.

Here, in brief, is what I have learned through genealogical research:

The youngest of 10 children, Stanley Eugene Nelson was born Feb. 6, 1926, in the small city of Crookston, seat of Polk County, in northwestern Minnesota. He completed high school in Bremerton, Washington. On June 30, 1942 — at 19 years of age, light complected, standing 5-foot-10, weighing 150 pounds — he signed his World War II draft registration card and then joined the U.S. Navy.

He spent six years in the Navy, serving aboard the USS Thatcher DD-514, becoming a weapons technician third class (petty officer), and earning a Purple Heart. In 1948 he married Darlene Curry, and they had two daughters, Dale and Sue. In 1953, he enlisted in the U.S. Air Force, serving at Elmendorf Air Force Base as a civil engineer from 1953 until his retirement in 1968.

He then lived the remainder of his life in Anchorage, dying at age 78 on Jan. 28, 2005. He was buried, with military honors, in the Fort Richardson National Cemetery.

Stan and Darlene Nelson were, according to my longtime neighbor Mary France, good friends of Dave and Donna Thomas, a couple who would one day live between the Frances and the Fairs on Forest Lane, between Soldotna and Sterling. In fact, in Anchorage Donna used to babysit for the Nelsons.

Mary said that the Thomases and the Nelsons both decided in late 1958 or early 1959 to homestead in the Soldotna area, so Stan and Dave traveled together from Anchorage to the peninsula, staked parcels they liked on a snaking 200-foot-high terrace above the middle Kenai River, and filed on adjacent homesteads.

On April 27, 1959, Nelson’s homesteading application was received and filed in the Anchorage Land Office; the land he was applying for contained three connected blocks — one of 80 acres, one of 40 acres, and one of 46.42 acres along the river. On Dec. 8, 1959, Nelson’s homestead entry was “allowed,” meaning that it was officially authorized by the Bureau of Land Management. And by April 1960 his residency had been established with the Land Office. He could therefore begin legally working on the land.

After that, Stan and Dave journeyed south on weekends to their properties, planning to create a shared road into them. In Anchorage, Stan bought an old, fairly decrepit military track vehicle with a blade on the front to facilitate rudimentary road building.

He hauled the machine from Anchorage down to Longmere Lake, nestled just off the Sterling Highway between Soldotna and Sterling. The far shore of the lake lay only a short distance through the woods from the Thomas and Nelson homesteads, and it was there — near where Dave and Donna would briefly live in a trailer before building their own home above the river — that they stored the small dozer and awaited warmer days.

Mary’s husband, Dan, called the dozer a “piece-of-shit Cat,” although it wasn’t a Caterpillar. In those days, many bladed track vehicles were called Cats, but Dan’s disdain for this one stemmed from its rickety construction and its frequent and inopportune tendency to throw one of its tracks.

Although Dave and Dan appreciated having someone help provide access to their property, they spent considerable time razzing Stan and generally cracking jokes about his exasperating tractor. Work stoppages and cursing were frequent. Dan, an adept mechanic who aided in the road-building project because the Frances had filed on 80 acres next to Dave and Donna, said that on one particularly aggravating day the Cat expelled its track (thus causing it to be reinstalled) seven times.

Portions of the land in and around the three homesteads had been scorched in the 1947 Kenai Burn, which had ravaged 310,000 acres of the western Kenai Peninsula. Prone and leaning deadfalls and dead standing trees were numerous among the new low growth returning to the mixed deciduous-coniferous woods.

Across this tumbled and tangled terrain, the three men carved a twisting path, scraping off the moss and the root mass and shoving aside a steady berm of fire victims and thin topsoil. It was strictly a summer road at this point, ungraveled and unditched, mostly mud and soft brown earth, barely wide enough for a single four-wheel-drive vehicle.

The last day Stanley Nelson operated his Cat probably occurred between the summer of 1960 and the summer of 1961. Whatever the specific day, the end of the road-building came quickly and with violence when Stan decided to run his blade right into a big charred birch, instead of maneuvering around it.

Vibrations from the impact traveled up the trunk. Higher up, the shivering generated a whip-like motion that snapped off the top of the tree and sent it plummeting straight for Stan. He had no covered cab, no safety helmet, and no chance to escape what was nearly a widow-maker. I’m not sure he even saw it coming.

The blow connected with his head, neck and back. Dan and Dave scrambled to transport him out of the woods to Kenai, where he was air-evacuated to a hospital in Anchorage. His injuries robbed Stan of his homesteading enthusiasm, and he decided at some point to surrender his rights to the property.

At the time of Stan’s change of heart, Dan and Mary were living near us in Burton Carver’s trailer court in Soldotna. We had arrived in town — what town there was then, with a population of about 300 people — on Oct. 3, 1960. Sometime during the summer of 1961, the Frances informed my parents that Stan was letting his homestead go, and they urged Mom and Dad to make Stan an offer.

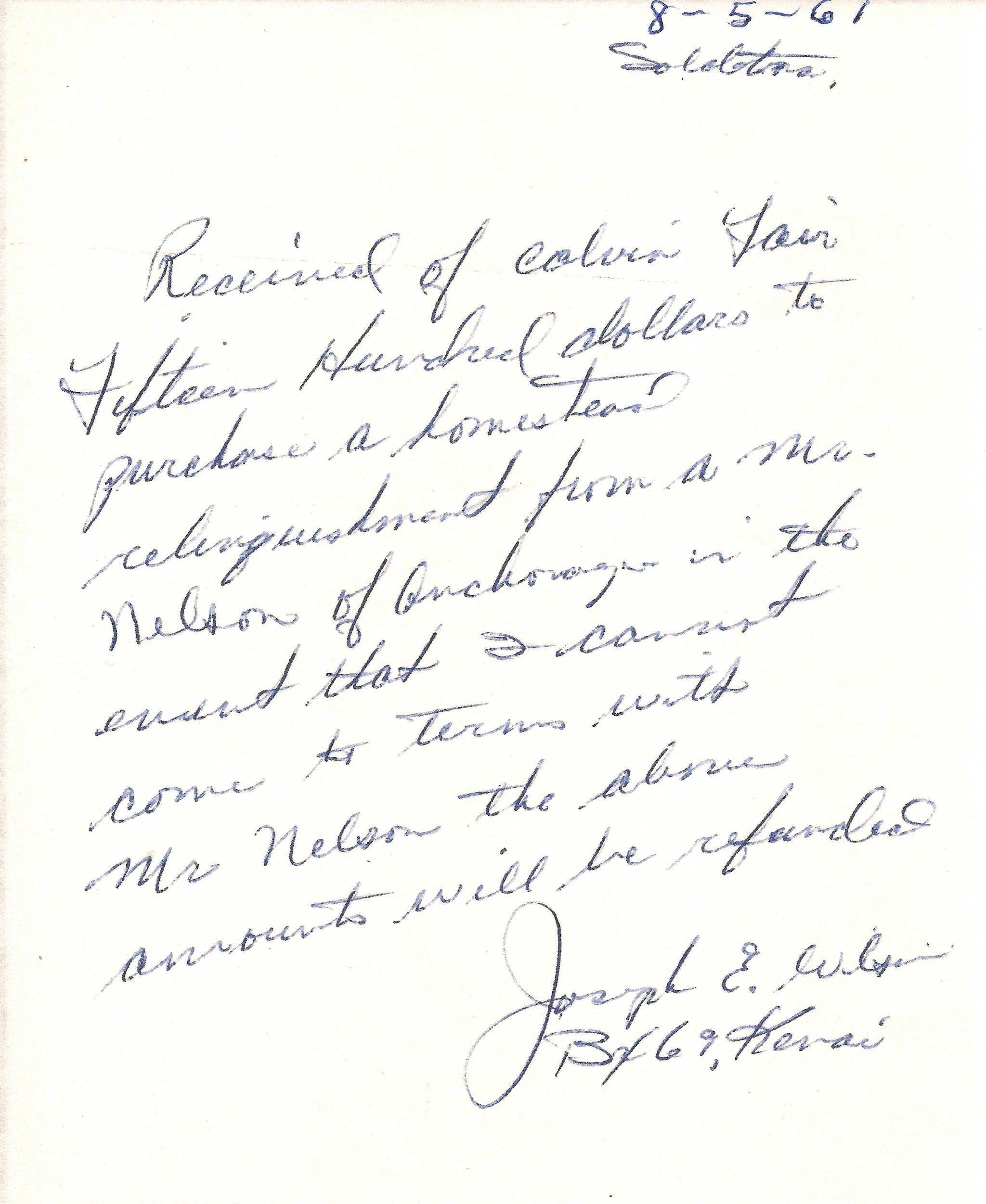

Mom told me that Dad, who generally eschewed confrontation and disliked negotiation, had no desire to personally handle a land transaction. He hired Joseph E. Wilson, of Kenai, to take care of the details for him.

Wilson, a land locater and surveyor during the peninsula’s homesteading era, wrote a receipt on Aug. 5, 1961, stating that he had received $1,500 from Dad to “purchase a homestead relinquishment from a Mr. Nelson of Anchorage.” He added: “In the event that I cannot come to terms with Mr. Nelson, the above amount will be refunded.”

No reimbursement was necessary. Wilson and Nelson quickly struck a deal.

Six days after Wilson wrote the receipt, my father’s homestead entry application was received by the BLM. On the same day, according to BLM records, the “case” concerning Stanley Nelson’s claim on this homestead was closed officially. Dad was billed a filing fee of $16, plus an “advance filing fee” of $8.75 because the parcel was slightly larger than the standard 160 acres.

And so it went. Loss and gain. While the Nelsons settled back into life in Anchorage, the Thomases, Frances and Fairs became homesteading neighbors at the end of Forest Lane, their lives interwoven for decades.

• By Clark Fair, For the Peninsula Clarion