NEW YORK — Don Stratton, one of the few remaining surviving veterans from the bombing of Pearl Harbor, had been holding on to his memories for more than 70 years.

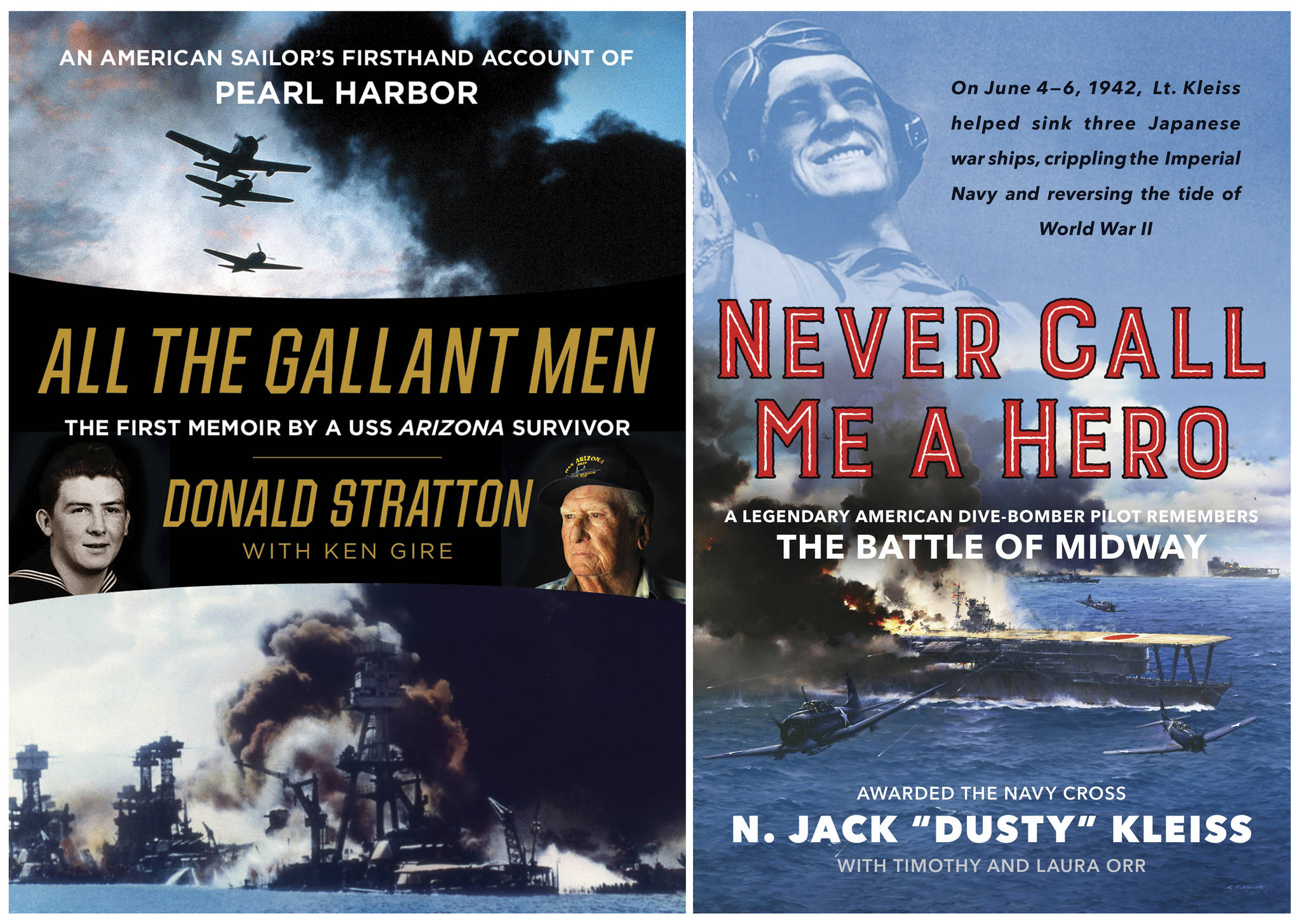

“It’s a long story and a hard one,” says Stratton, 95, whose memoir, “All the Gallant Men,” about his experiences on the USS Arizona, came out in 2016. “We lost so many men that day, friends of mine. I’m not sure how many people are interested in this anymore, but I’ve had a lot of people call me and say they’ve read my story and recommended it to others.”

Stratton’s book is among a recent wave of World War II memoirs notable in part because it may well be the last wave. Even veterans who were teenagers when the war ended in 1945 are at or approaching 90 by now. The 75th anniversary of the Pearl Harbor attack came last December, and publishers will likely have a hard time finding fresh accounts for the 75th anniversaries of milestones such as D-Day (June 6, 1944) and V-J Day (Aug. 14, 1945). According to the U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs, some 558,000 World War II veterans are still alive, a fraction of the millions who survived the conflict. By the end of the decade, the number is expected to drop to under 300,000.

At the National World War II Museum, in New Orleans, a yearslong project to record veteran’s accounts is winding down after compiling more than 9,000 interviews.

“We have fewer personnel for oral history gathering, and the veterans we’re getting have become more difficult to talk to,” says Robert Citino, the museum’s senior historian. “I don’t think it’s surprising that we have people who don’t recall events with 100 percent accuracy. We’re just dedicated to getting every oral history we can.”

“The number of memoirs that could be published in the coming years will get fewer and fewer,” says Ray Merriam, whose Merriam Press has published numerous World War II books. Merriam cites the age of surviving veterans as just one factor.

“Many vets simply don’t feel they have an interesting enough story to tell,” he says. “Many don’t feel they have the ability to write about their experiences. Some of the memoirs I have published, the veteran has had it edited professionally, but that is an expense that not everyone can afford.”

World War II books are a vast and popular genre, and soldiers have shared memories in everything from Studs Terkel’s Pulitzer Prize-winning oral history, “The Good War,” to “Band of Brothers” and other best-sellers by Stephen Ambrose. Many of the great fiction writers of the mid-20th century, including Norman Mailer, Kurt Vonnegut and James Jones, served in the war and wrote classic novels based on their experiences. Virtually all of those authors have died.

Some recent memoirs are posthumous works brought to publication by friends or family members, such as “Tail-End Charley,” which compiles the private writings of the late World War II pilot James E. Brown, or “Nothing Impossible,” the story of World War II major and POW Wallace Clement as remembered by his friend Sean Heuvel. Others were projects that began when the veteran was still alive. In 2011, the naval historians Timothy and Laura Orr saw a television interview with Lt. N. Jack “Dusty” Kleiss, a pilot who sank two Japanese carriers during the Battle of Midway. They spoke with him and decided his story was worth a full-length book. Kleiss died in the spring of 2016, about a year before the publication of his memoir, “Never Call Me a Hero.”

“One of the things he said to us often was that he had never talked about the Battle of Midway; even his kids had very little knowledge of what he did,” says Laura Orr. “And everyone he knew had started dying, so they couldn’t tell their stories. And he would tell us about some of the people who didn’t make it back at all. He was the last one standing and he felt he needed to get it out there.”

Stratton’s book, too, was not initiated by him. A couple of years ago, a radio segment about Stratton aired in Colorado and was heard by Gretchen Anthony, the daughter of author Kenneth Gire. Anthony thought Stratton’s story would be ideal for a book and contacted her father.

“I just cold-called him and told him, ‘I don’t even know if you would be interested in doing a book, but I’d like to work on it with you,’” says Gire, who specializes in religious books. “And he said, ‘Yes, I would like to do one, but I never knew how.’”