“Saving Mr. Banks”

Walt Disney Pictures

2 hours, 5 minutes

There’s a scene late in this week’s “Saving Mr. Banks” that elevates the film from simply an entertaining little biopic to something much more meaningful.

There are plenty of good scenes in the film, but most of them are just what you’d expect from the trailer — crisp, cutting British remarks in response to good natured American hucksterism as “Mary Poppins” author P.L. Travers faces off with Walt Disney over the rights to her story. The movie is entertaining and interesting, funny and sweet, though not particularly enlightening or illuminating — all but for the scene in question. More on that later.

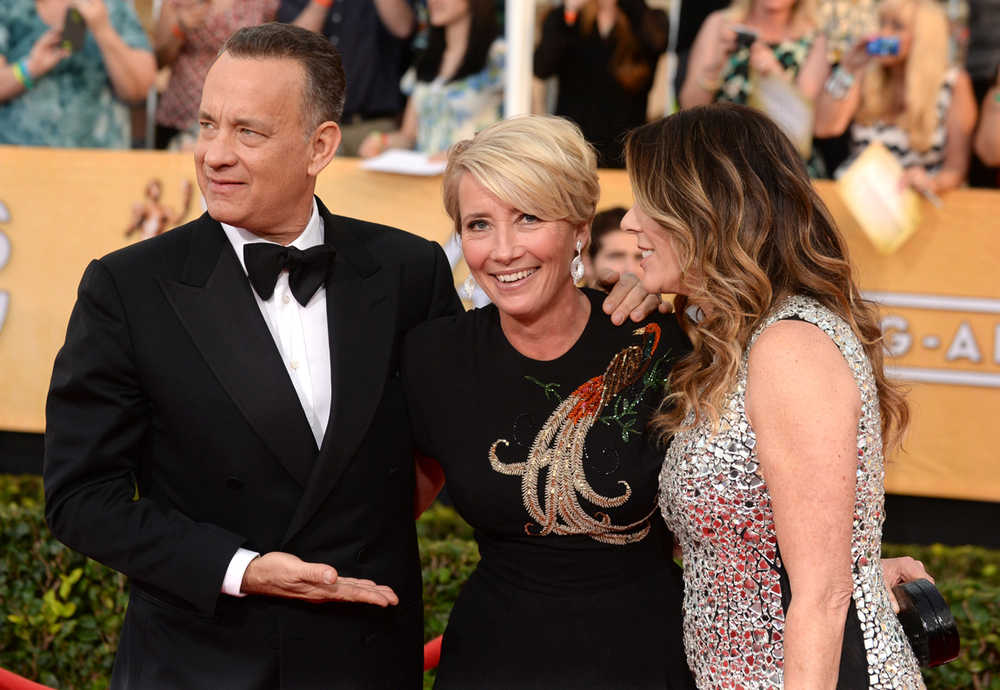

Travers, who is at the heart of this story, is played in yet another spot-on performance by Emma Thompson. The film opens with the author en route to Los Angeles to meet with Tom Hanks’ Walt Disney, cut with frequent flashbacks to the author’s childhood in rural Australia. Travers is a difficult woman, given to melancholy and definitely not at all interested in turning her tale of a magical nanny over to what she sees as the king of glitz and empty-headed fluff.

When she arrives at Disney Studios, Mrs. Travers is greeted by her writing team, a trio of good natured Californians that immediately set her teeth on edge. “Saving Mr. Banks” is populated by excellent actors in small roles, including Bradley Whitford as the head writer, and Jason Schwartzman and B.J. Novak as song writing brothers Bob and Dick Sherman. As the film progresses, we see Travers as she struggles to contain and hold sacrosanct her vision, while returning to the dusty outback in scene after scene designed to shed light on Travers’ present-day demeanor.

I appreciated the effort, but the flashback structure in the film is probably the least effective element in it. Clunky and more than a little obvious, I would have preferred the combination of the two eras to be a little more nuanced. Still, the childhood scenes are well-done and offer the real meat of the story. Collin Farrell does a very good job as a kind and loving, though completely incapable father. His scenes are some of the most heartbreaking of the film. Also very good is Ruth Wilson as the mother, exhausted, terrified, and using every little bit of strength she has to hold it together for the family.

As the young P.L. Travers, I was very impressed with young actress Annie Rose Buckley, whose quiet presence adds a real power to her role that histrionics never could. Back in present day, I was pleased to see Paul Giamatti in a role that requires very little other than as a little friendly comic relief. He plays Ralph, Travers’ appointed driver and one of the only people who seems to be able to stand her.

As a whole piece of cinema, “Banks” isn’t nearly as powerful and engaging as you’d imagine a Tom Hanks film released at the height of Oscar season would be. That’s not a criticism, necessarily. The movie is light, that’s all, and Tom Hanks, though good, isn’t giving much more of an effort than simply doing a professional impression. The film pushes all the right buttons, hits the right notes, but remained less than thought-provoking until the scene I mentioned at the beginning of this review.

Walt, in a last ditch effort to obtain the rights to “Poppins,” relates a story of his own childhood to Mrs. Travers, connecting to her own difficult upbringing. I won’t spoil the whole scene by relating it word for word, but the crux of it was this: that storytellers have the power to restore order in the world. At that, something clicked in me, as well as in Mrs. Travers.

I like that thought — that writers, godlike, can correct the ugly truths in the real world by putting them to rights in the pages of fiction or up on the silver screen. It’s not exactly a novel notion that writers have the ability to write happy things as opposed to sad ones, but when it comes to serious literature, the tendency always seems to be to lean toward accuracy — that a harsh and pitiless view of the real world is somehow a richer truth, that cynicism and honesty go hand in hand.

No so, claims Mr. Disney, who holds, rather, that writers, in painting their stories on a bright canvas, can take what is broken in reality and fix it, bringing back the joy that once was missing. In one masterful stroke, not only does Walt Disney break down the walls surrounding the heart of this sad, bitter woman, but simultaneously offers up a stellar defense of his entire candy-colored, multi-million dollar empire.

I don’t have any idea if Walt really said this. He was reputedly very congenial, and a consummate businessman, but whether he actually used this bit of logic to melt P.L. Travers heart, who can say? Taking the film’s advice however, I’ll say who cares? It gave me something to think about and made me happy and, according to Mr. Hanks’ Disney, that’s all that matters.

Grade: A-

“Saving Mr. Banks” is rated PG-13 for mild language and adult themes.

Chris Jenness is a freelance graphic designer, artist and movie buff who lives in Nikiski.