During the past two summers, I have had strange encounters with a duck flying through the woods on my property. Usually in the dusky early morning hours while I was getting ready for work, this duck would zoom through the forest, frequently flaring like it was trying to find a place to land. Several times it even landed on a large tree branch for a moment then zoomed off again. To give you a lay of the land, I am in a fairly wooded area about half a mile from the Kenai River and there are no ponds or swamps that might attract most waterfowl. When the bird finally slowed down long enough for me to get a look, I recognized it was a Common Goldeneye.

Why would it be attracted to my property? Both Common and Barrow’s Goldeneye are diving ducks that prefer to nest in tree cavities. I have always tried to leave the snags of dead or dying birch and spruce trees on my property to attract birds, something this female goldeneye apparently found to be quite agreeable. Unfortunately, she has never found the right tree, but she continues to look each summer.

Common and Barrow’s Goldeneye nest on the Kenai Peninsula. They are often found during winter on the Kenai River and Skilak and Tustumena Lakes when open water persists. They are also fairly common in marine areas around Seward and Homer. A quick review of data from the Bird Banding Laboratory in Patuxent, Maryland, reveals that not all of the wintering goldeneyes in south-coastal waters are “ours,” but other mysteries are still unresolved.

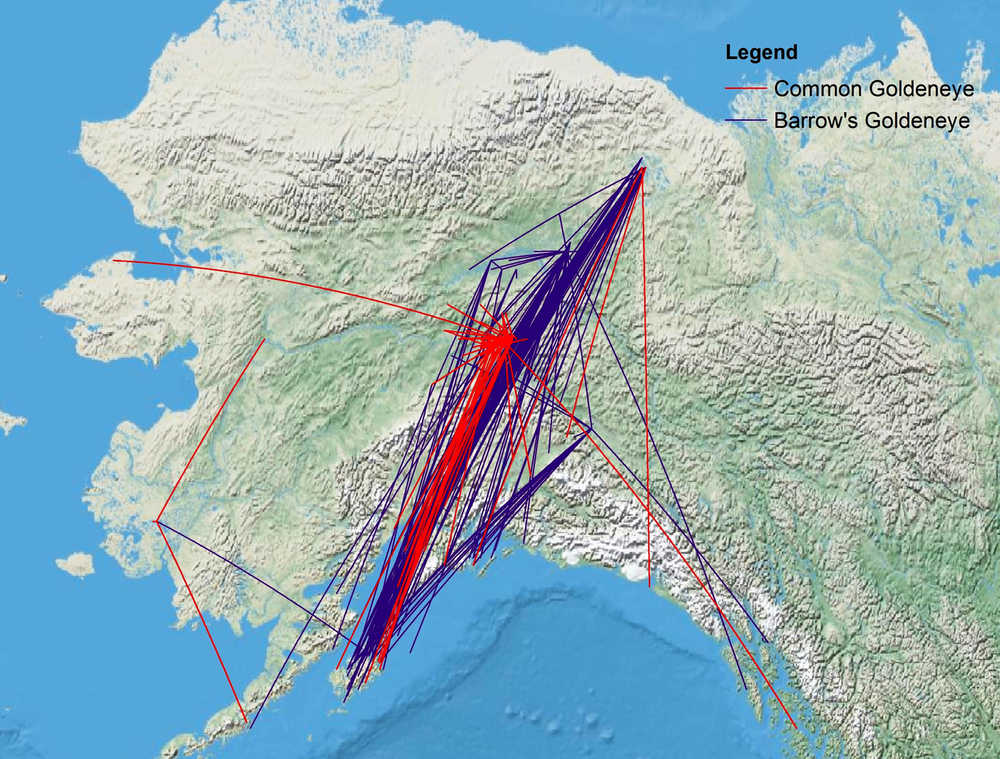

There are dozens of records of Common Goldeneye banded as nestlings in the Fairbanks area that were eventually harvested during the duck hunting season on the Kenai Peninsula or Kodiak. Barrow’s Goldeneye have been banded in several areas including near the Yukon River, Tok, Vuntut National Park in the Yukon Territory, and a handful on the southern Kenai Peninsula near Halibut Cove. For the most part, they all were shot or found dead in the same wintering areas here in south-coastal Alaska.

What the banding data do not reveal are what all the other goldeneyes nesting around the state do in winter as there are only a few places on their nesting grounds where they have been studied. Significantly more research has been conducted on both duck species in British Columbia. There, satellite transmitters tracked their movements as they left the wintering areas where they were initially captured, then to their breeding grounds, then to areas where they molt, and finally back to their original wintering grounds. These studies indicate there is generally little spatial overlap among sub-populations from different breeding areas and wintering areas. So, Fairbanks birds predominantly go to Kodiak and the southern Kenai Peninsula, but very occasionally one will go to southeast Alaska instead.

After the Exxon Valdez oil spill, there was a lot of research conducted on both goldeneyes around Prince William Sound. The studies showed that the birds primarily eat bivalves near shore during the winter. Bivalves are filter feeders, ultimately collecting, storing and transferring whatever toxins are in the water to the birds eating them. Since they filter a lot of water for their own food, they can actually store hydrocarbons in fat tissues at a much higher concentration then they themselves are encountering in the environment. Ten years after the spill, birds from oiled areas were still exhibiting higher concentrations of hydrocarbons and other contaminants than those from non-oiled areas. Evidence of hydrocarbon exposure in goldeneyes eventually declined almost two decades after the spill.

The knowledge we gain from bands and satellite transmitters tells a story that is both good and bad for goldeneyes. These ducks appear to be fairly rigid about where they nest and where they winter. Thus a catastrophic event in our near-coastal waters could be devastating for an entire wintering area and associated breeding sub-population. On the brighter side, we would hope that an event like that would not impact their entire wintering range along the coast from the Alaska Peninsula to northern California, so the population as a whole should be safe from a smaller scale event.

Whether you are a casual bird watcher or an avid duck hunter, we can all agree that even when you’re looking down to see where your feet are going through the marsh, you can’t fail to hear the whistling wings of a flock of goldeneyes flying overhead at Mach 6. If your goal is to finally recover a duck band while hunting, goldeneyes are probably not your best bet —your likelihood of encountering a banded pintail is four times greater than a banded goldeneye. Your best bet to recover a leg band is still from a Canada Goose, for which you are eight times more likely to encounter one than on both goldeneye species combined.

Todd Eskelin is a Wildlife Biologist at Kenai National Wildlife Refuge. He specializes in birds and has studied songbirds in many areas of Alaska. Find more information about the refuge at http://www.fws.gov/refuge/kenai/ or http://www.facebook.com/kenainationalwildliferefuge.