One of the epic moments for any waterfowl hunter is the discovery of a bird band on the leg of one of their downed ducks. Prior to that discovery, the ducks harvested are appreciated for their beauty, the enjoyment of the hunt, and the anticipation of a delicious dinner shared among friends and family. But put a leg band on that duck and now there is a history attached to that 8 digit number and the bird has a different level of significance.

Recently, a relatively new duck hunter asked me where he would have the best chances of shooting a banded duck and if there was a particular species that would improve his chances. He had been hunting for 3 seasons and had harvested a lot of ducks and geese without a single band showing up in his bag. So I set out to answer his question and started with the Bird Banding Laboratory in Patuxent, Maryland. As a bander myself, I know all bird banding data are stored in this national database.

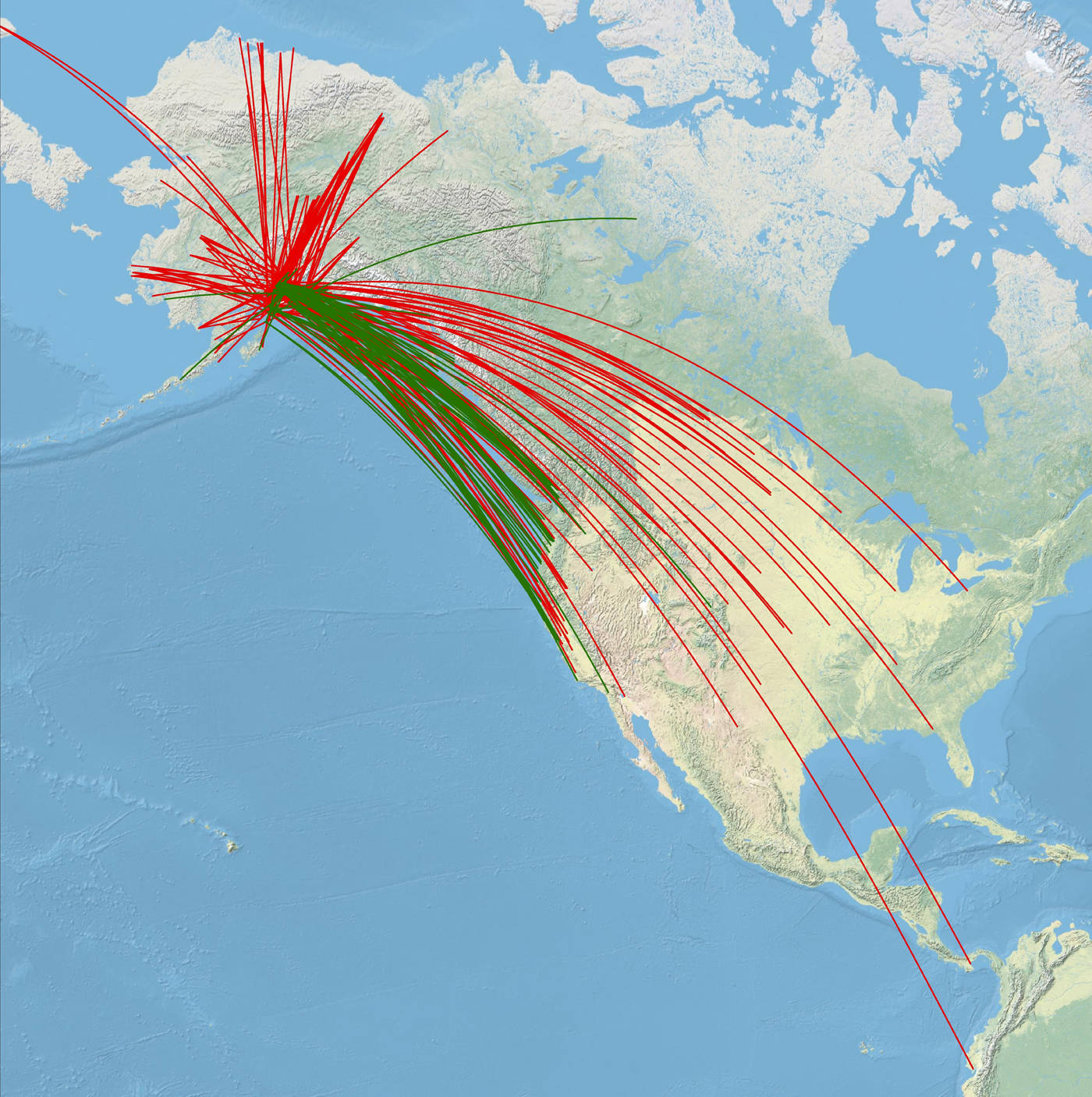

I was able to access the banding lab’s database and filter the birds that had been encountered at some point after they were banded. Next I set the filters for all species banded on the Kenai Peninsula and encountered elsewhere or birds banded elsewhere and encountered on the Kenai. This database holds approximately 64 million banding records just since 1960 (which is as far back as the electronic version of these data go). Out of those banded birds, the lab has received encounter information on about 4 million bands or a little over 6 percent. Recovery rates are much higher for hunted species like ducks and geese than they are for non-hunted species like songbirds.

On the Kenai Peninsula, there are very few non-waterfowl related encounters. Roughly 3,700 of 3,800 band encounters that involved the Kenai Peninsula were waterfowl (97 percent). It was also very apparent from the data that if my waterfowl hunting friend was determined to get a banded bird, he should focus his efforts on Cackling and Canada Geese, and Mallards. Between 2014 and 2016 they accounted for 84 percent of the band encounters in our area.

Days later after emerging from this mountain of data, I had a strange sense of connectivity just from pouring over the data points. I wanted to go see Hays, Kansas where an American Robin was banded in January 1976 and killed by a cat in June 1977 in Kenai, Alaska — a distance over 2,600 miles. Then I want to go visit a banding location on the outskirts of Cleveland, Ohio, where a Myrtle Warbler was banded in October 1982. It subsequently struck a window and died in May 1983 near Beaver Loop Road after just finishing its 3,100 mile flight back to Alaska.

What did it look like at Posorja, Ecuador where a Semi-palmated Sandpiper was banded in the winter and then spotted on the Kenai Flats late the following summer on its way back to Ecuador? It didn’t even get frequent flier miles for the 14,000 mile round trip flight. I even discovered that an Orange-crowned Warbler I banded near Lower Russian Lake was found dead near the Bear Creek Golf Club in Murrieta, California.

Looking back at the waterfowl records, I found that the Kenai Peninsula truly is a melting pot. We have Mallards that were banded in Mississippi, Tennessee, Oregon, Washington and Alberta, Canada, that have all been encountered on the Kenai Peninsula. Our Cackling and Canada Geese also range from the Great Lakes to the Klamath Basin. I always thought that waterfowl passing through the Kenai Peninsula were bound for the West Coast for the winter, but it is only from the banding records that we know we have ducks from all three flyways crossing our skies.

Digging through the histories of these individual birds, I realized I felt the same draw my band seeking friend had while out hunting. It was the same excitement I had when I first started banding birds in Portland, Oregon.

In The Sand County Almanac (1949), Aldo Leopold wrote something that summarizes it perfectly for me, prompting me early in my career to work hard and achieve the skills needed to obtain a bird banding permit. “To band a bird is to hold a ticket in a great lottery. Most of us hold tickets on our own survival, but we buy them from the insurance company which knows too much to sell us a really sporting chance. It is an exercise in objectivity to hold a ticket on the banded sparrow that falleth, or on the banded chickadee that may someday re-enter your trap, and thus prove he is still alive.”

Todd Eskelin is a Wildlife Biologist at Kenai National Wildlife Refuge. He specializes in birds and has conducted research on songbirds in many areas of the state. Find more information about the Refuge at http://www.fws.gov/refuge/kenai/ or http://www.facebook.com/kenainationalwildliferefuge.