The Kenai National Wildlife Refuge was established in 1980 with passage of the Alaska National Interest Lands Conservation Act (ANILCA). Prior to ANILCA, refuge lands were managed as the Kenai National Moose Range. The Moose Range was designated in 1941 by President Franklin D. Roosevelt because, as a big game hunter, he was concerned that populations of the giant Kenai moose were not being properly managed and would be overexploited.

By the 1980s, wildlife management had expanded to include concepts from the emerging field of conservation biology. Managers were thinking more holistically about entire ecosystems rather than single species management. ANILCA expanded the purpose of Kenai Refuge to “conserve fish and wildlife populations and habitats in their natural diversity.” Diversity in this context is focused on biodiversity which includes maintaining both species diversity and genetic diversity.

Another type of natural diversity is geodiversity. Geodiversity is the diversity of enduring geophysical features such as topology, soil, and landforms. Resource managers have recently begun to focus on geodiversity as a way of responding to rapid climate change. Before climate change emerged as a conservation issue, managers could use the current distribution of ecosystems or species for conservation planning. However, climate change requires new thinking by managers because distributions cannot be assumed to remain stable.

Plants and animals are responding to new climate conditions by moving, and ecosystems are reorganizing as species move. Paul Beier, a professor in the School of Forestry at Northern Arizona University, has suggested that managers should focus on geodiversity instead of species. Dr. Beier calls this approach “conserving nature’s stage.” Invoking William Shakespeare’s play “As You Like It,” species are the actors and geodiversity is the stage. Climate change will change the script of the play. In other words, species will shift and ecosystems will reorganize, but areas with similar geophysical characteristics should host similar species and ecosystems. Therefore, these geophysical features should be used for conservation planning because protecting geodiversity will ultimately protect biodiversity.

The Nature Conservancy has championed this conservation planning approach. Mark Anderson, a senior scientist at The Nature Conservancy, has led a research initiative using geodiversity to identify areas in the Eastern U.S. that can be used to protect biodiversity in a changing climate (http://maps.tnc.org/resilientland/). The Nature Conservancy has evaluated the current conservation estate in that region and, with a $37 million grant from the Doris Duke Foundation, is purchasing lands that will provide better representation of geodiversity in the conservation portfolio.

In Alaska, ANILCA delineated a large Federal conservation estate. Approximately 130 million acres of National Park Service and National Wildlife Refuge System lands were designated in the state. Congress deliberately created large reserves to ensure that natural landscape processes remain intact because these ecosystem processes are necessary to sustain subsistence lifestyles for Alaskans.

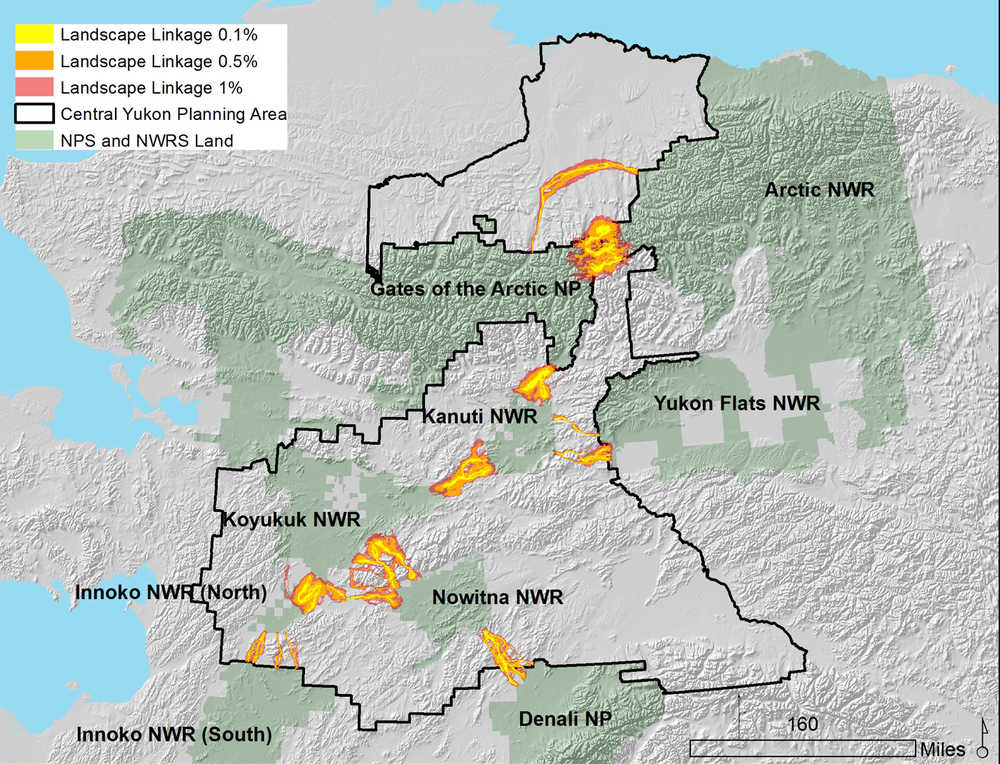

Although we are blessed with these large and intact conservation units, Alaska is experiencing rapid and large magnitude climate change. The state is already experiencing and adapting to real impacts, such as melting permafrost, increasing coastal erosion, and loss of sea ice. Species will need to move across Alaska as conditions change. In partnership with other federal agencies, I have conducted a geodiveristy analysis to identify key linkages between parks and refuges (see photo) using a methodology developed by Brian Brost, a graduate student of Paul Beier. Coordination among agencies to maintain landscape permeability — such as building wildlife crossing structures over or under highways — could allow species (actors) to move across the conservation stage.

Here on the Kenai Peninsula, more than 4 million acres are managed by Federal agencies. The Kenai National Wildlife Refuge, Kenai Fjords National Park and Chugach National Forest form a contiguous conservation estate that is dissected by the Seward and Sterling Highways. The refuge is collaborating with the Alaska Department of Transportation & Public Facilities to construct strategically-placed underpasses so wildlife can move more freely across the 22-mile section of the highway between Sterling and Jim’s Landing. Elsewhere on the Kenai Peninsula, an interagency working group is taking a closer look at the 11-mile wide isthmus that connects the Kenai to the mainland but also bottlenecks wildlife dispersal on and off the peninsula.

Geodiversity analysis can also be used as one lens to think about whether the landscape is permeable (or not) to a wide variety of species. Maintaining connectivity between geologic features will allow species to reshuffle in a rapidly changing climate, minimizing species extinctions and ensuring resilient biological communities as our future heats up.

Dr. Dawn Robin Magness is a Fish & Wildlife Biologist at the Kenai National Wildlife Refuge. Find more information at http://kenai.fws.gov or http://www.facebook.com/kenainationalwildliferefuge.