Our early spring, sunny days, and warm temperatures this summer changed my behavior. I considered planting my garden early, but my fear of frost over-rode that instinct. I wore shorts and spent more time swimming in lakes. And I’ve been thinking about how birds may have changed what they did this summer.

Many of our songbirds winter as far away as South America. I wonder if and how these summer migrants take advantage of the longer growing season and warmer temperatures that we’ve seen on the Kenai Peninsula the last few decades. There is evidence worldwide that some bird species are arriving on their breeding grounds earlier, nesting earlier, and wintering further to the north. Local birders and refuge staff have also noted new species overwintering, earlier arrivals of migrants and later departures from the Kenai Peninsula.

I wanted to take a closer look to see if some bird species are shifting the time they spend here more than other species. In his well-researched book “The Avian Migrant: The Biology of Bird Migration,” Dr. John Rappole notes there is a continuum of birds from facultative migrants to obligate migrants. Facultative migrants are more flexible and move in response to conditions.

In contrast, obligate migrants are genetically hard-wired to migrate at certain times. Obligate migrants are generally, but not always, long distance migrants. This type of hard-wired migration timing would develop when seasonal patterns are very predictable because individuals that consistently got the timing right, using cues such as day length, are more likely to pass their genes to the next generation. However, because day length will not change as climate changes, these bird species may be less likely to take advantage of longer growing seasons.

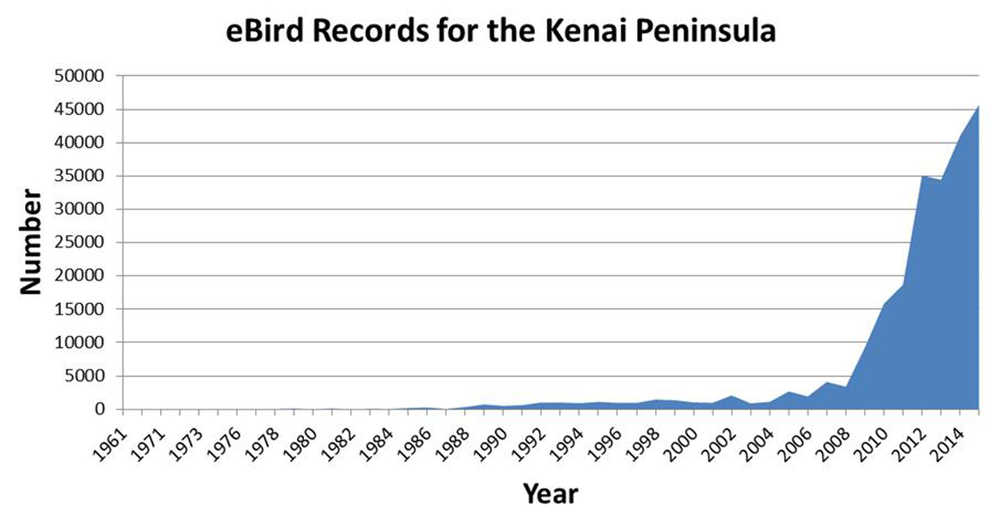

I began to explore which birds on the Kenai have rigid or flexible migration timing using eBird data. EBird is a website (www.ebird.org) that networks observations of recreational and professional birders. Though the website was launched in 2002 by the Cornell Lab of Ornithology and the National Audubon Society, the first bird observations included in eBird date back to 1961 for the Kenai Peninsula.

However, observations are sparse until 2008 when local birders began to extensively use the online checklist program. I cannot adequately thank the birders who populate eBird for the information they provide. When enough people consistently add data, and enough species are observed on enough days throughout the year, then we can construct arrival and departure dates.

Thanks to Mrs. Mary A Smith (later Mary Miller), I was able to extend our understanding of arrival and departure dates to the 1960s. Smith was an avid birder who lived in Cohoe, right here on the Kenai Peninsula. I became aware of Mrs. Smith because her daily bird checklists were used to develop a bird checklist for the Kenai National Wildlife Refuge (formally the Kenai National Moose Range) in 1968.

A quick search online revealed that Smith was a very good birder who even co-authored scientific papers about birds on the Kenai Peninsula. Todd Eskelin, a birder and biologist at the Refuge, shared photocopies of a checklist notebook from 1961 and 1962. Although some species are not well represented because they do not occur where she lived, Mary Smith’s dedication to completing a checklist each day provides a good estimate of when birds arrived and departed Cohoe.

Using this information, I did see a continuum in how much different Kenai bird species have shifted the amount of time they spend here. Some species, like the Swainson’s Thrush and Blackpoll Warbler, are arriving and departing at nearly the same time as in the 1960s. Both are long-distance migrants. Swainson’s Thrush breed in the boreal forest and winter in southern Mexico and Central America. Blackpoll Warblers migrate from Alaska to northeastern South America.

In contrast, other species have shifted to spend more time here. White-crowned Sparrows seem to overwinter now, extending the time this species are observed here by 200 days! Varied Thrush are spending on average 145 more days on the Kenai Peninsula and over-wintered in Seward and Homer in 2013 and 2014. A paper published in 1965 in the “The Condor” reported that a few White-crowned Sparrows were seen at feeders in Anchorage in the 1960s, but not on the Kenai Peninsula. Varied Thrush were not documented anywhere in Alaska during winters at that time.

Both White-crowned Sparrows and Varied Thrush are shorter distance migrants. White-crowned Sparrows winter in the Lower 48 and Varied Thrush winter mainly in California. Seeing these birds in the winter does not give insight into whether individual of either species are now full-time residents or if these are individuals that breed further north and now winter here.

Yellow-rumped Warblers breed in the boreal forest and winter along coastlines of the U.S. and in Mexico. Interestingly, these warblers arrive at the same time as they did in the 1960s, but are staying 41 extra days in the fall.

At this point, I have more questions than answers about if and how birds are changing. It is not clear if species with rigid migration timing, like the Swainson’s Thrush and Blackpoll Warbler, are less successful because they have not arrived and nested earlier as the growing season becomes extended in Alaska. I also wonder if birds that arrive early and depart late are unique or the norm for the species. This is why science is fun — one question invariably leads to another.

Dr. Dawn Robin Magness is a Landscape Ecologist at the Kenai National Wildlife Refuge. Readers who have stories about Mrs. Mary Smith are welcome to contact me (260-2814). Find more information about the Refuge at http://www.fws.gov/refuge/kenai/ or http://www.facebook.com/kenainationalwildliferefuge.