In December, I started a project I had hoped would be over rather quickly. But to my surprise, I’m still enjoying it. After three months of inputting specimen data from our herbarium and insect collection into the online database Arctos, I find that I really appreciate what I thought was going to be a tedious task.

Here at Kenai National Wildlife Refuge, we have thousands of plant and insect specimens in our collection, some dating back to 1949. For years, these sat in our lab, occasionally pulled out of cabinets by biologists seeking to identify a new sample or to see if a species had been found here previously. Otherwise, these specimens weren’t used all that often.

Our pressed or pinned specimens are housed in the “specimen room”, which contains several cabinets, numerous drawers and countless folders. Although organized taxonomically, it takes effort to locate a specific specimen, not knowing if we actually have a given species without searching through the collection. To be honest, the effort to search for a specimen that may or may not be there was not always worth it. Beyond that, our collections were only accessible to those who were physically present at the Refuge.

So how does inputting these specimens into Arctos make our collection more useful? Well, most of us understand that it’s good to have an online record of important documents or samples, but this project is so much more than just inventorying and archiving data.

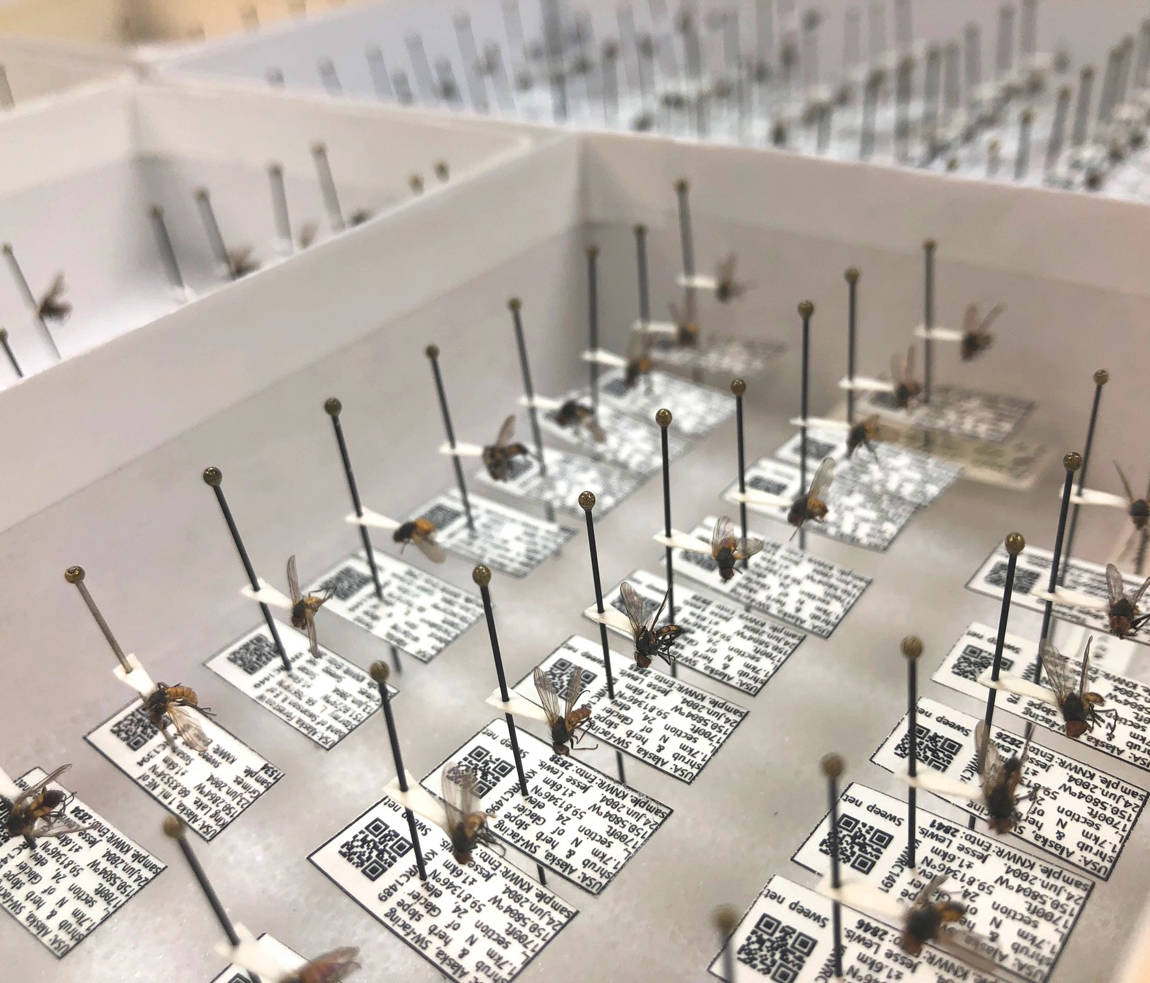

Arctos requires a lot of additional information beyond simply identification including names of the collectors and ID determiner, date of collection and determination, habitat, specific location and GPS coordinates, and a unique barcode label. Before each specimen is entered, I add that unique barcode label to the herbarium sheet or insect label which is then used to “track” the specimen. Each element of our specimen room (building, room, cabinet, drawer or folder) also has its own barcode so that once entered into Arctos, we can scan a specimen into its correct location. Now, when we search for a specimen, we know exactly where it is located and find it easily!

Currently, the Kenai Refuge has over 10,300 plant, insect, and other invertebrate records in Arctos and we are still inputting more. Our Arctos records are now discoverable to anyone! Although an interested party can’t physically get their hands on them (unless we arrange a loan), our specimens have tangible value since all of the data associated with each record is accessible and useable anywhere, anytime!

These records are used to determine species distributions, historical ranges, and countless other things. They can be cited in publications and referenced for research. One of the coolest features of Arctos is that it is linked to third party databases such as The Global Biodiversity Information Facility or GBIF. Through GBIF, Kenai Refuge data are now accessible internationally!

Arctos isn’t the only database we use to track species on the Refuge. While out in the field, we can log observations without taking an actual sample through iNaturalist. This database has its own app that lets you simply enter a photo of the specimen while it automatically records the time, date, and GPS coordinates! You can enter an identification or, if you’re uncertain what it is, leave it blank —other users then correct the identification based on your photos and their knowledge of the area. An observation will change from the designation “Needs ID” to “Research Grade” when more than two thirds of identifiers agree on a taxon. As one my favorite tools, I’ve used it both personally and professionally whenever I come across a new organism.

Another database we use is the Alaska Exotic Plants Information Clearinghouse or AKEPIC. Every year we log all of the invasive species we observed on and off the Refuge with dates, GPS coordinates, and any management actions taken. AKEPIC tracks the whereabouts of all invasive species observed in Alaska, including a plant profile and its invasiveness ranking. This information is used by numerous agencies and universities.

It is one thing for the Kenai Refuge to have a bunch of data on its own, but it is so much more valuable to have our data be discoverable and used by others. That is what we are striving to do here at the Refuge —after all, we are a public agency. We continuously acquire new data and work to make it all accessible as soon as possible.

If you are curious and want to explore our specimen records, go to the websites of Arctos, iNaturalist, and AKEPIC to easily find more data than you might imagine.

Kyra Clark is a seasonal biological technician at Kenai National Wildlife Refuge. Find more information about the Refuge at http://www.fws.gov/refuge/kenai/ or http://www.facebook.com/kenainationalwildliferefuge.