“Sometimes one thing leads to another.” This is a quote from a Refuge Notebook article I had written about the Kenai Peninsula’s first exotic freshwater snail, the big-ear radix (Radix auricularia), last January. I had been referring to the past, but more was to come. Soon after the article appeared in the Clarion I was contacted by retired geologist Dr. Dick Reger, who disagreed with statements in my article. He thought that this snail might be native.

As a geologist, Dick had studied freshwater snails and clams in old sediments in our area to determine past conditions. He had also collected and identified many local freshwater snail specimens, even putting together a draft field guide to the freshwater molluscs of the Kenai Peninsula. Based on what he knew of the present distribution of the big-ear radix snail in Alaska, he doubted that it had been introduced.

We dug into this question of whether or not the big-ear radix is exotic to our area. A literature search and expert opinion supported my first conclusion: the current understanding was that all populations of this snail currently in North America were the result of introduction from Europe.

The history of Radix auricularia in North America goes back to before 1869 when it was found near Troy, New York, apparently introduced with plants from Europe. By the early 1900s it had spread to multiple locations in the Great Lakes. Currently, this exotic species is still expanding its range in the western U.S. and Canada.

We had a new piece of information, though. Back in 2016 when we collected a big-ear radix from Stormy Lake near Nikiski, we had sent off a tissue sample for identification by DNA barcoding, an inexpensive identification method using standardized, short sequences of DNA. We had received an identification of Radix auricularia, confirming our initial identification, but we had not examined the genetic data further.

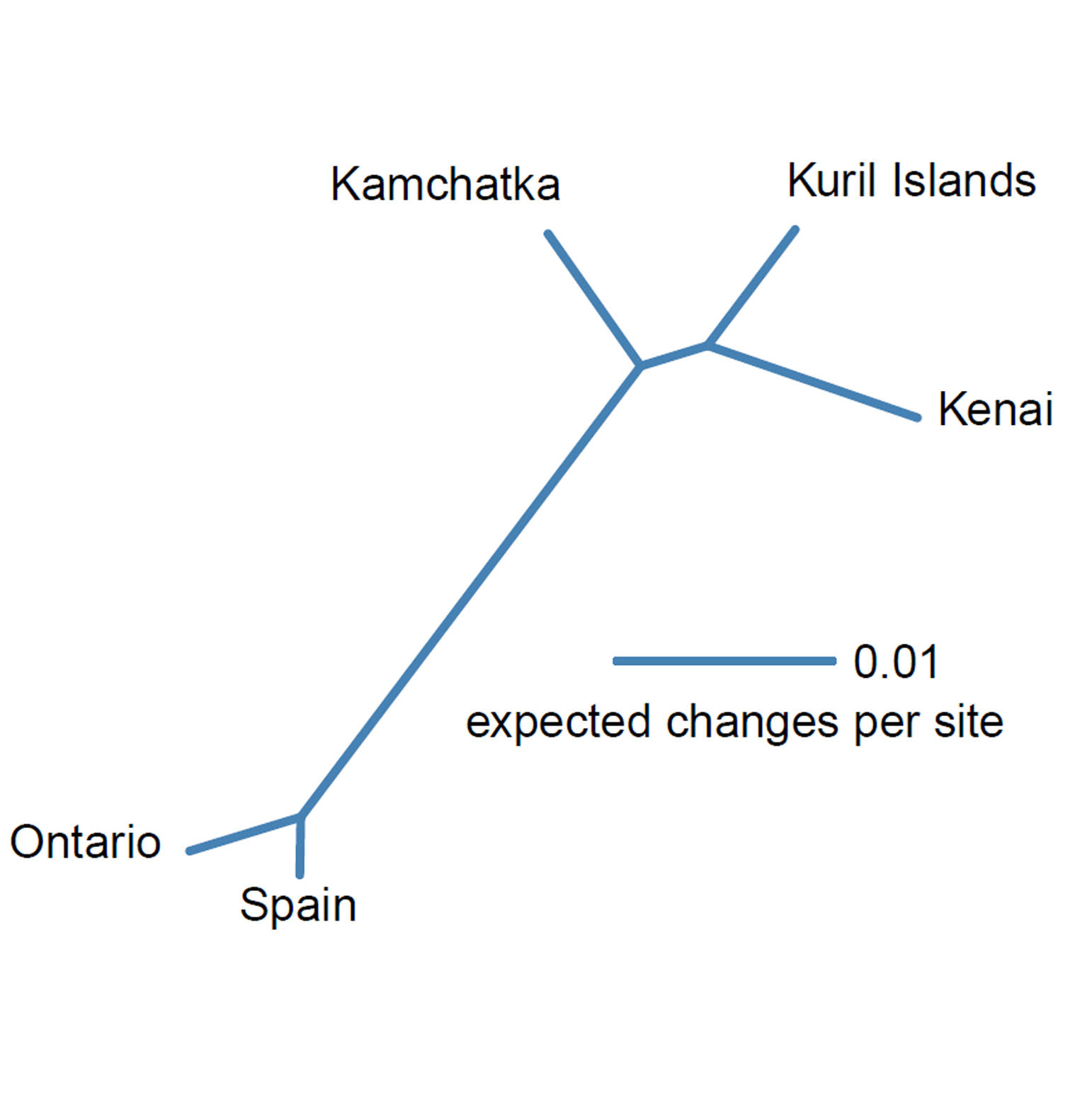

So I compared the Kenai sequence with DNA barcode sequences of Radix auricularia from around the world that were publicly available through online databases. The barcode sequence from the Kenai Peninsula specimen was closest to sequences from Kamchatka and the Kuril Islands in East Asia, and less similar to sequences from Western Europe and eastern North America. A second DNA barcode sequence from another Kenai Peninsula specimen lent to me by Dick Reger matched the Stormy Lake sequence. The pattern suggests that in North America there are now two lineages of big-ear radix snails: one in eastern North America introduced from Europe and one native lineage in Alaska.

We now believe that the Kenai Peninsula population of Radix snails is a Beringian relict, one of many species in our region that have persisted from a time when parts of the Yukon, Alaska, and Siberia were connected and free of ice while much of northern North America was covered in glaciers. Based on the recent genetic data, our understanding of the provenance of the big-ear radix in Alaska has changed from exotic invasive to Alaskan endemic. Because this knowledge affects how this species is managed, it would be appropriate to follow up by obtaining DNA barcode sequences of Radix snails from other parts of western North America to determine if populations there are exotic or native.

We expect to have more complete information on the Alaskan big-ear radix population soon. In the summer of 2017 Dr. Ilya Vikhrev and Dr. Olga Aksenova, both from the Russian Academy of Science, collected freshwater molluscs (including the big-ear radix) from the Kenai National Wildlife Refuge and other places in Alaska as part of a study on trans-Beringian molluscs. Their team had already produced the DNA barcode sequences from Kamchatka and the Kuril Islands with which I had compared my sequences. They will be thoroughly scrutinizing the Alaskan specimens and their DNA sequences to better understand their relationships and history.

Learning through science is not always a linear process, but the unexpected is part of what makes this kind of work interesting. I will keep you posted when we learn more. I am especially grateful to Dick Reger for all his help and continued interest in this topic.

Matt Bowser serves as Entomologist at the Kenai National Wildlife Refuge. Find more information at http://www.fws.gov/refuge/kenai/ or http://www.facebook.com/kenainationalwildliferefuge.