This month marks the 140th birthday of J.N. “Ding” Darling. Ding was a political cartoonist and a key figure in American wildlife management and conservation. After noticing a tribute in my son’s Ranger Rick Magazine, I began reading a biography by David Lendt titled, “Ding: The Life of Jay Norwood Darling.” As I read his life story, I cannot help reflecting on how his drawings, political satire and love of wildlife helped to establish the lands we have access to here, such as the Kenai National Wildlife Refuge.

Ding Darling was born on Oct. 21, 1876. His father’s work as a minister moved the family from northern Michigan to Indiana and finally to Sioux City, Iowa, when Ding Darling was 10 years old. At that time, Sioux City was on the edge of the frontier. Ding hunted and fished a prairie landscape where game, such as the Greater Prairie Chicken, was abundant. He watched the prairie chicken become a rarity as grasslands were subdivided and plowed, an experience that molded his values. He once said, “If I could put together all the virgin landscapes which I knew in my youth and show what has happened to them in one generation it would be the best object lesson in conservation that could be printed.”

Ding began carrying around a sketch pad as a boy. His unflattering, yet recognizable, cartoons of faculty during a stint as the yearbook art editor at Beloit College in Wisconsin earned him a year-long suspension. He did manage to graduate in 1900 and returned to Sioux City to work as a sketch artist and journalist for the local newspaper.

Some of his first cartoons supported President Theodore Roosevelt’s conservation efforts. In 1903, President Roosevelt established the first National Wildlife Refuge, Pelican Island, with an executive order to provide a sanctuary for birds being overhunted because feathers were needed for the fashion industry. In less than a decade, Roosevelt went on to establish a total of 52 bird and 4 big game reserves — the beginnings of the National Wildlife Refuge System.

Fortunately, Ding’s talent brought in a job offer from the Des Moines Register and Leader because he was fired in 1906 for offending his previous publisher with a drawing of the Sioux City school board president. In Des Moines, Ding had the freedom to draw provocative political cartoons about a wide-range of subjects. By the time he retired in 1949, Ding Darling had become a household name, his cartoons syndicated in 150 newspapers nation-wide and the recipient of two Pulitzer Prizes.

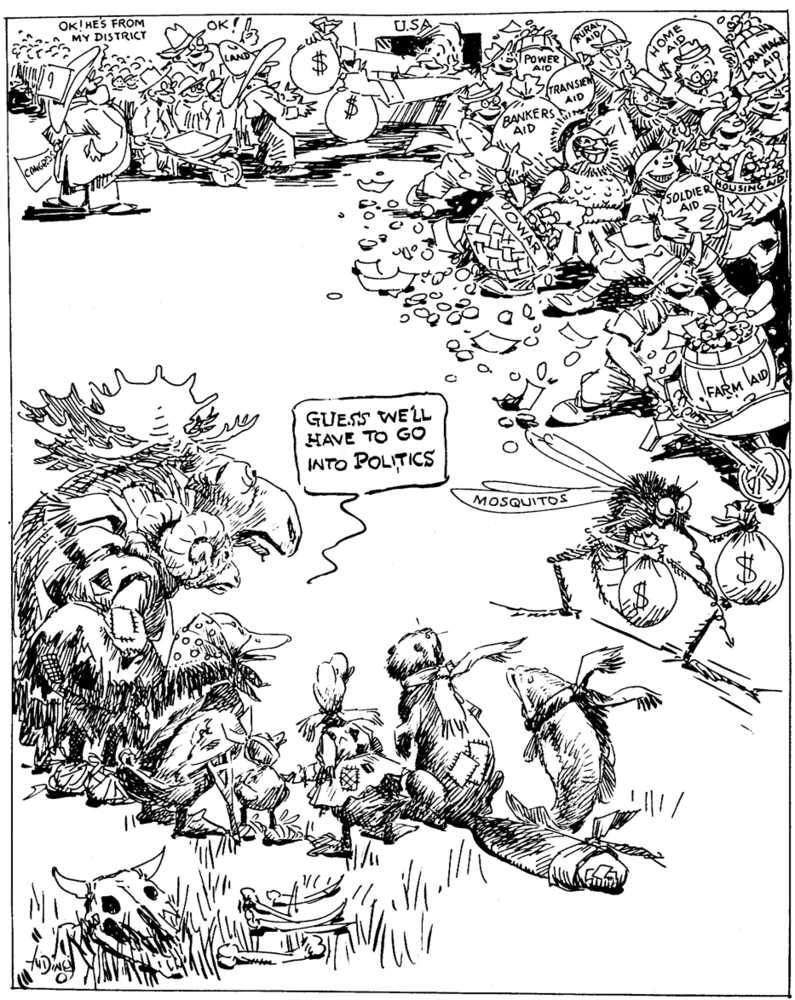

Ding Darling was an active member of the Grand Old Party (GOP). After being a delegate to the Republican National Convention in 1932, he could barely squash rumors and calls for him to run for a senate seat in Iowa. He was unwilling to run for political office because he felt he would lose the freedom and independence he exercised as a cartoonist to unabashedly critique policies. He was frustrated that short-term political considerations kept politicians from doing what was needed to conserve limited natural resources.

In the 1930s, the Dust Bowl was a national crisis. Drought coupled with the agricultural practice of deep plowing the prairies resulted in the irrevocable loss of topsoil blowing away in the wind. Waterfowl populations were in steep decline. Ding had been serving on the Iowa Fish and Game Commission and on an advisory board that was recommending seasons and bag limits for waterfowl.

In 1934, President Franklin Roosevelt appointed Ding Darling and other forward thinkers in wildlife management, such as Aldo Leopold, to the Committee on Wild-Life Restoration. The Committee on Wild-Life Restoration recommended the federal government purchase 12 million acres of marginal lands for wildlife purposes and that funding be provided to restore and manage these lands. Concurrently, The Migratory Bird Hunting Stamp Act, commonly called the Duck Stamp Act, was moving through Congress. The Duck Stamp Act required hunters to purchase a stamp to generate money for habitat protection, management and enforcement.

After those recommendations, President Franklin D. Roosevelt asked Ding to serve as Chief of the Bureau of Biological Survey (precursor to the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service). At first, Ding was reluctant to “aid and abet” the political opposition. However, Ding was promised the funding to build the refuge program. Four days after his appointment was announced, President Roosevelt signed the Duck Stamp Bill.

Ding only served for 18 months, but in that time he designed the first Federal Duck Stamp. He worked tirelessly to reorganize the Bureau of Biological Survey into an effective agency and needled the President and Congress for the funding needed to implement his vision. Under his tenure, the agency cracked down on illegal market hunting, began purchasing and restoring retired agricultural lands for wildlife, and instituted hunting restrictions to allow waterfowl populations to recover.

The Alaska National Interest Lands Conservation Act (ANILCA) designated 76 million acres of land in our state as national refuges. Two million of those acres comprise the Kenai National Wildlife Refuge, established 4 decades before ANILCA, as much Ding’s legacy as it was President Roosevelt’s. Ding Darling fought for wildlife to have a place in developing landscapes, as reflected in his cartoon “Nobody’s Constituents.” Reading about Ding’s life has made me even more appreciative that life on the Kenai Peninsula includes ready access to large tracks of land set aside for wildlife.

Dr. Dawn Robin Magness is the landscape ecologist at the Kenai National Wildlife Refuge. You can find more information at http://www.fws.gov/refuge/kenai/ or http://www.facebook.com/kenainationalwildliferefuge.