In the world of wildlife and fisheries management, the death of an animal does not always directly equate to one less animal in the population. For the animal that died, this effect on the population demographics is moot. As Kurt Vonnegut wrote in the 1961 novel Mother Night, “when you’re dead, you’re dead.”

But for the larger population, the timing of the death (and the sex and age of the individual) is everything. Wildlife biologists and managers distinguish between compensatory versus additive mortality in a population. Disease, starvation, predation, and even cannibalism or infanticide can be sources of natural mortality in wild populations. One of the effects of human intrusion into a natural landscape is incidental mortality of wildlife caused by birds striking windows, raptors electrocuted on utility transformers, bears killed in defense of life or property, or vehicles colliding with moose. These human sources of mortality are generally considered additive to natural mortality.

However, when it comes to game species, harvest by humans for recreational or subsistence hunting and trapping can be a source of additive or compensatory mortality depending on when it occurs. For many game species, young-of-the year disperse in the autumn, temporarily exceeding the carrying capacity of their habitats. This is true for many species with high reproductive rates and short life spans such as spruce grouse and snowshoe hares. As fall turns to winter, their broods and litters are fated to die by one means or another so that populations are sustained around the carrying capacity of their habitats for the remainder of the year.

And because these young can be considered a “doomed surplus,” it is a good time for us to harvest them for human consumption. Paul Errington, a now-deceased Professor of Zoology at Iowa State University, was the first to define hunting during this time of surplus as a form of compensatory mortality. By that, Dr. Errington meant that the following year’s reproductive rate would increase or decrease to compensate for variations in populations, a form of density-dependent regulation. His observation of an inverse relationship between density and the proportion of young is, as Aldo Leopold put it, “the scientific explanation of why game can be hunted at all.”

In contrast, excessive or ill-timed hunting may be additive, cumulatively adding to rates of natural mortality with the result that populations can be reduced below their habitat’s carrying capacity.

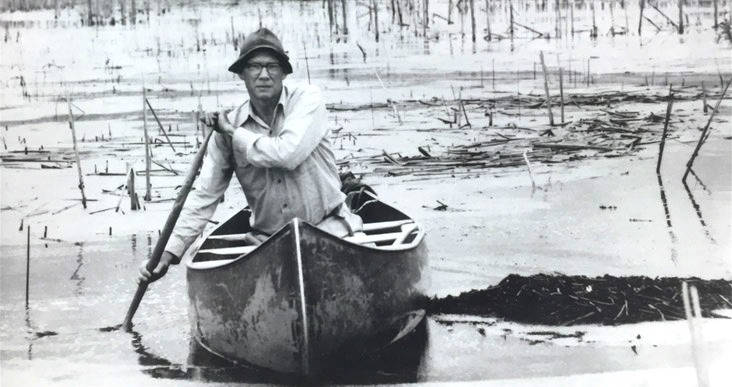

Errington is considered one of the giants in Wildlife Management, both a mentee and colleague of Aldo Leopold, and a recipient of The Wildlife Society’s Aldo Leopold Award in 1962. An ardent hunter and trapper, he also authored over 200 scientific articles and four books. He studied the effects of predation and disease on muskrat demographics for decades, his insights into their life history from 30,000 hours of field observations ultimately redefining the role of predation and establishing the basis for modern harvest management.

He wrote that people confuse “the fact of predation with effect of predation.” By that, he meant that an act of predation does not necessarily result in a reduction in the prey population. Here on the Kenai National Wildlife Refuge, a young-of-the-year fool’s hen eaten by a coyote in the fall or shot by a hunter may not translate to one less spruce grouse the following year. “Predation,” he wrote, “belongs in the equation of Life.”

And so the father of the theory of compensatory mortality, the very basis for contemporary harvest management, became a vocal critic of predator control during his day. Errington also pushed back on people who spoke of some wildlife being pests if they were not for human consumption or some other human resource. In a 1947 essay entitled “A Question of Values,” published in the Journal of Wildlife Management, he wrote “Let it be understood that among so-called vermin are some of our most beautiful and valuable wild creatures.”

Having earned my undergraduate degree in Wildlife Ecology from the University of Wisconsin at Madison, in the department started by Aldo Leopold from which Paul Errington earned his Ph.D., I first learned about Errington four decades ago. But I’m only now really beginning to appreciate how ahead he was of his time.

I encourage you to explore his thinking on your own. His classic 1957 book, “Of Men and Marshes,” was reprinted in 1996 and is an easy read during these long (but waning) winter nights.

Dr. John Morton is the supervisory biologist at Kenai National Wildlife Refuge. Find more information about the Refuge athttp://www.fws.gov/refuge/kenai/ or http://www.facebook.com/kenainationalwildliferefuge.