If you lived in the woods on the Kenai Peninsula in the 1990s, you may not want to read this article. Those were the years when the spruce bark beetle outbreak killed more than 3 million acres of mature spruce forest on the Kenai. Living out Homer’s East End Road, my wife and I spent our weekends cutting down our beautiful old-growth Sitka spruce trees and burning the slash. Our view improved dramatically, but so did the cold wind coming up from Kachemak Bay, as well as the vehicle noise from the road.

Spruce bark beetles thrive on runs of warm summers, and the present 3-year run of sunny summers should trigger another burst of beetle activity. My research as an ecologist at the Kenai National Wildlife Refuge during the 1990s focused on the history and causes of bark beetle outbreaks. Using tree-ring analysis (dendrochronology), my colleagues and I developed a 250-year record of bark beetle outbreaks all around Cook Inlet. The last major outbreak was in the 1880s when many stands on the Kenai and in Katmai and Lake Clark National Parks were heavily thinned, similar to the 1990s. There were smaller regional outbreaks in the 1970s, 1910s, 1850s and 1810s, as well as local outbreaks at other times.

The peculiar ecology of spruce bark beetles allows them to kill only larger trees. Pole-sized trees are spared and are released from competing with neighboring trees to grow rapidly and rebuild a new forest. Bark beetles bore through the outer bark and lay their eggs in galleries within the sugar-rich inner bark (phloem). Small trees not only produce a lot of pitch that can cement the mother beetles in their galleries, Mafia-style, they also have thin phloem that can be too tight for a beetle. Big trees, however, are fat city for bark beetles. The strategy of mass attack allows thousands of beetles to completely overwhelm the tree’s pitch defense and eat all the phloem, girdling the tree just as if the bark had been stripped off with an axe.

The phloem cylinder around a tree carries the sugar produced in the needles by photosynthesis down to the roots for storage over the winter. In spring, the sugar comes up as watery sap through the sapwood (the outer several inches of trunk wood) and the sugar feeds the new needles. If the phloem plumbing has been cut by girdling, the sugar never gets to the roots and only zero-calorie sap rises in the spring. The old needles turn red and the tree dies. After a year in the red-needle stage, the needles fall off and only a “gray ghost” of a tree remains.

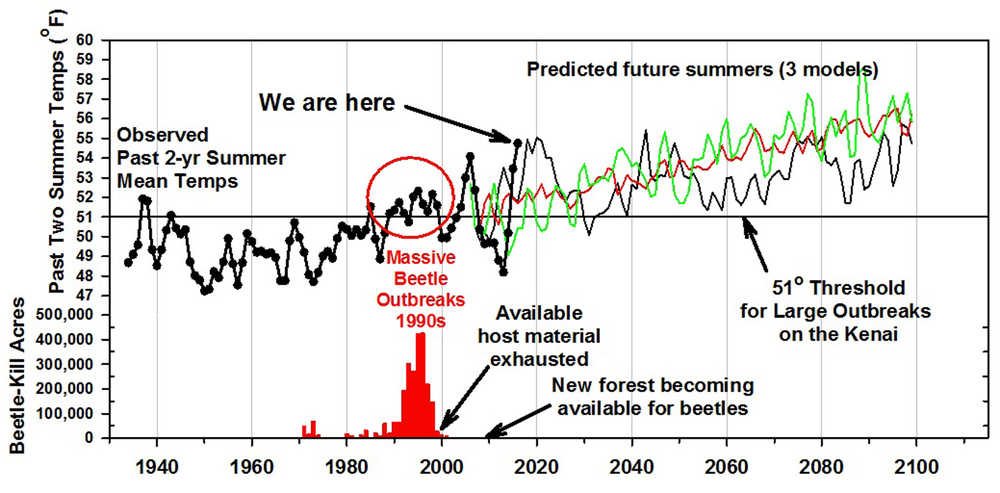

Two factors control bark beetle outbreaks: adequate host material (enough large trees) and runs of warm summers. The forest gun must be loaded with mature trees, so to speak, and warm summers must pull the trigger. The natural growth of the forest loads the gun, and the El Nino climate cycle provides the runs of warm summers to pull the trigger. A run of cool summers (La Nina) will shut outbreaks down. My research found that there is a distinct temperature threshold for large outbreaks — average May-August temperatures in Homer must be at least 51 degrees Fahrenheit for two or more summers. The last 3 summers have been well above this threshold (2013 – 52.5 degrees, 2014 – 54.4 degrees, 2015 – 55.1 degrees), and the present El Nino is predicted to be one of the strongest on record.

The climate trigger has now been pulled, but is the gun loaded? The gun was very well loaded in the 1990s — foresters considered the forest “overmature,” at least for timber harvesting. The present spruce forest has rebounded quite quickly, primarily through growth release of pre-outbreak understory poles, as well as recruitment of new seedlings. Today’s forest is certainly not mature, but many trees have grown big enough (at least 6 inches in diameter) to host bark beetles. So the gun is at least partially loaded. That said, however, it still may take several summers to build up enough beetles to the point where they can really use mass attack effectively.

Bark beetles are always present at low (endemic) levels in the forest. The USDA Forest Service flies annual aerial surveys for all kinds of forest pests and diseases. This summer’s survey found spruce beetle mortality higher than the last couple of years, but still low, according to a preliminary report. Red needle acreage was mapped across Cook Inlet between the lower Susitna River and the east end of Lake Clark Pass. A slight increase was seen in the Point MacKenzie to Big Lake area and on the west side the Kenai Peninsula, but still the numbers were low compared to past outbreaks when several hundred thousand acres of fresh beetle-kill were reported every summer.

The future of spruce in southern Alaska seems grim, at least for the upland species of Sitka and white spruce, and the Sitka-white hybrid Lutz spruce. As the graphic shows, global climate models forecast generally rising summer temperatures. After 2030 these models indicate that May-August average temperatures on the southern Kenai will consistently be above 51 degrees, suggesting there will always be beetles attacking spruce large enough to eat. If true, tomorrow’s spruce could be harvested for pulp, but would rarely grow to saw-timber size.

On a brighter note, I don’t expect the next outbreak to be anywhere as severe as the 1990s outbreak for the simple reason that we don’t have the available breeding habitat. Yes, we have some newly mature trees, but only a finite number of beetles can fit into the available phloem. In the 1990s we had forests not substantially thinned since the 1880s, so there was plenty of phloem (and warm summers) to breed enough beetles for many years of mass attack. We’ll likely have warm summers in the future, above the 51-degree threshold, but the endemic beetle population will act like a thermostat that keeps the spruce forest at a new, lower equilibrium. In place of spruce we can expect to see lots more hardwoods, resulting from increased fire activity, which in turn should provide more winter browse for the Giant Kenai Moose, to borrow a term from the 1890s.

Dr. Ed Berg retired as an ecologist from the US Fish & Wildlife Service in 2010. He will teach a course on Global Climate Change at the Kachemak Bay Campus this fall. A longer version of this article was published in the Homer News, homernews.com. Find more information on Kenai National Wildlife Refuge at www.fws.gov/refuge/kenai/ or www.facebook.com/kenainationalwildliferefuge.