Author’s note: This is Part One of a three-part story about the S.S. Dora, the tenacious steamship that plied the coastal waters of Alaska for four decades over a century ago.

The ordeal for the crew of the S.S. Dora began ordinarily enough: Known for having the longest and most northerly mail route in the world, the steamship launched from Seward on Dec. 2, 1905, bound for Cold Bay, Dutch Harbor and other points “to the westward.”

Despite heavy seas and some delays, she made her scheduled stops all the way west, but on the return trip she departed the Kodiak harbor on Dec. 24 and was not seen again for two months.

Typically, the Dora’s winter mail run lasted about 20 days. This one, which was never completed, lasted four times as long.

According to newspaper reports of the time and to historians Coleen Mielke and Mary J. Barry, the Dora was in rough water about 15 miles from the port of Chignik when the weather intensified. Gale-force winds churned the seas and lashed the 112-foot steamer. Waves crashed over her deck.

The Dora’s nine-foot-long boiler, forged of half-inch iron and powered by a furnace capable of burning nearly 3,000 pounds of coal per day, was jolted hard enough to dislodge it eight inches out of position.

Steam pipes bent and burst. The primary source of energy for the ship’s engine was cut off.

The crew raised the sails, but frigid temperatures quickly sheathed the upper hull, the rigging and the sails with ice. Powerless, the Dora drifted for three weeks.

With no radio communication and with winds shoving them ever southward and farther out to sea, the ship’s crew could only ride out the storm and hope for a warming trend.

Whenever temperatures climbed sufficiently and winter storms abated enough to use the sails, Capt. Zeb Moore directed the ship toward the West Coast, once nearing Vancouver Island before being blown back out to sea.

Thus, the Dora zigged and zagged across open water for another month. According to an article in the Alaska Daily Empire (Juneau) in 1918, the ship was blown “nearly to Honolulu.”

By mid-February, the Dora had been reported as missing. The ship, her crew and a handful of passengers were presumed lost. Lloyd’s of London prepared to issue an insurance pay-off to her owners, the Northwest Steamship Company.

Then, on Feb. 24, the owners received a cablegram from Port Angeles, Wash., informing them that the Dora had survived, battered but intact, with all on board safe. According to Mielke, the Dora had been sighted, moving “under shredded sails,” near the Strait of Juan de Fuca and had been towed to Port Angeles for repairs.

Such was life for the S.S. Dora. In her early years—when she was known more for carrying passengers and freight—a standing joke developed among locals along her route: Somehow the Dora managed to strike every rock or reef between Seattle and Seward but just kept going.

Later, as a mail boat, she continued ramming into rocks and grounding on sandbars. After the application of a few quick patches to the hull or a long layover for repairs in dry-dock, she was back in action again.

Somehow, like a ship with nine lives, she survived to sail another day. And another.

The Dora traveled from the West Coast to Southeast Alaska, to Prince William Sound and Cook Inlet, to Bristol Bay and the Aleutian Islands, and occasionally all the way to Nome.

Sanford J. “Sam” Mills, one of the most successful early gold seekers in the Kenai Mining District, used the Dora to reach locations in upper Cook Inlet. Before Seward was founded in 1903, the Dora regularly delivered men and supplies to Resurrection Bay. Before Homer was officially named, the Dora aided coal-mining enterprises in and around Kachemak Bay. She also deposited Seattle prospectors onto the eastside beaches of lower Cook Inlet, from Homer to Clam Gulch.

The Dora seemed ubiquitous, and her decades of adventure and service endeared her to those she supplied, those she rescued and those who only read of her exploits.

In 1918, looking back on her career, the Alaska Daily Empire remarked: “To the fishermen, cannerymen, prospectors and natives of the Westward, the Dora was the newspaper, the grocery boy, the mail carrier, the supply bearer and even a Santa Claus.”

When she finally left her route for good, she was dearly missed.

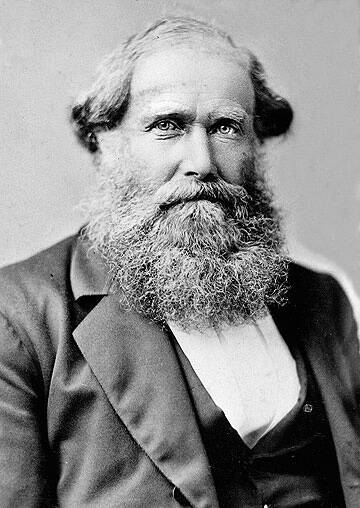

Well-known San Francisco shipbuilder, Capt. Matthew Turner, oversaw the construction of the S.S. Dora for the Alaska Commercial Company—specifically for its future president, the seal hunter Louis Schloss—in1879-80.

Turner was a prodigious, productive master builder, who, according to his obituary in 1909, designed, planned, modeled and constructed more than 225 sea-going vessels.

Initially considered a passenger steamship, the Dora made her maiden voyage on a calm, sunny April day in 1880, from the shipyard in Benicia, in the northern part of San Francisco Bay, to the Golden Gate Strait and back.

Experienced steamship men on board wagered on her average speed, most choosing between 6.75 and 7.75 knots. The fastest speed selected was approximately 8.13 knots, but the Dora exceeded all expectations, recording a pace of 8.25 knots.

A story about the launch the following day (April 8) in the Daily Alta California was glowing, even fawning at times, in its descriptions and assessments. The article mentioned how “the beauty of the day, the calmness of the water and the bright sunshine made the sail on the new and graceful steamer a veritable pleasure trip.”

Steamship officials on board ate a hearty lunch and, “over flowing goblets,” offered “many happy wishes for a successful and prosperous career” for the new steamer, which was scheduled to sail for Alaska early the next week.

Much of the remainder of the article focused on the Dora’s physical nature, from the “high-pressure cylinder (with) a diameter of eleven inches and the low-pressure twenty inches, with a twenty-inch stroke,” to the degree of tilt of its propeller. But to the average observer, the Dora’s most interesting attributes were those plainest to see.

At her widest point, the Dora, constructed of Puget Sound pine, measured 27 feet, and her gross weight was 320 tons. Her draught was 13.2 feet, and she was powered by an 80-horsepower “compound single-screw engine,” and a two-bladed prop measuring seven and a half feet in diameter. She was also equipped with two masts and a full set of sails.

Owner Louis Schloss first put the Dora to work carrying fur seal skins from the Pribilof Islands to California for the ACC. Seals in the Bering Sea were being killed by the thousands, and the Dora’s manifest was indicative of the death toll: more than 12,000 skins in 1880, and more than 15,000 in both 1881 and 1882.

Soon, however, the Dora became most widely known as a passenger ship. And the stories about her began.

There were the rescues—hundreds of passengers and crew members saved from greater privations or certain death. There were the narrow escapes—including surviving the ashfall from the Katmai eruption in 1912. And there were the accidents—a long list of bangs and bumps, of patchwork and major repairs, of wondering which misfortune might be her last.