AUTHOR’S NOTE: At the outset, I want to acknowledge invaluable contributions to this story from these three primary sources: the 2003 Hal Thornton memoir, “Alaska Odyssey: Gospel of the Wilderness”; the scholarship of Kasilof historian and writer Brent Johnson; and numerous contemporaneous newspaper articles and other documents.

The Crime

It was just before 7 p.m. on Monday, Jan. 19, 1948, in the small town of Kenai, Alaska. It was the dead of winter.

Hal Thornton, on his first-ever day in Kenai, was relaxing with Pappy and Jessie Belle Walker in their Quonset hut when Jimmy Minano raced up onto the Walkers’ porch and burst through the front door. “That jeep!” said Minano, indicating Thornton’s vehicle parked outside. “Take me to the marshal! There’s been a murder!”

The killing, Minano speculated, was the result of some “bad blood” between two men. Now, some of that blood had been spilled and was, in Thornton’s words, “staining a snowbank where one of them lay — the victim of a point-blank gun blast.”

A resident of Hope, Thornton was contemplating a move to Kenai with his wife and young daughter. The Walkers had offered him some advice and a place to spend the night.

At the moment, however, there were more pressing matters.

While the Walkers stayed put, Thornton and Minano motored toward the Marshal Allan Petersen residence, which included the Kenai jail. Once the stout, middle-aged marshal learned the few facts available, he moved quickly and resolutely into action.

Turning to Thornton, he said, “You and Jimmy get a posse in order. Do you mind using your jeep to gather up some men?”

Thornton didn’t mind. With directions from Minano, he drove to the home of Al and Jessie Munson, where two other Kenai newcomers, Henning and Ruth Johnson, happened to be visiting. Al and Henning joined the posse, as did another local man, Odman Kooly, and they all sped off toward the end of the road a short distance beyond the local cannery.

With rifles ready and flashlight beams dancing in the winter darkness, the posse set off on foot up the trail along the Kenai River toward the old, two-story Windy Wagner cabin (off present-day Beaver Loop Road), where the killer was said to be holed up.

Despite the inherent dangers posed by the accumulated manpower and firepower — plus a possibly desperate killer — the conclusion of the manhunt was anticlimactic: The accused, William Henry “Bill” Franke, was right where they thought he’d be. He was also unarmed. And he surrendered to the marshal without incident and was taken into custody.

Then he freely admitted to killing Ethen Cunningham.

It may have seemed like an open-and-shut case.

Life and the law are rarely so simple.

Ethen’s Path

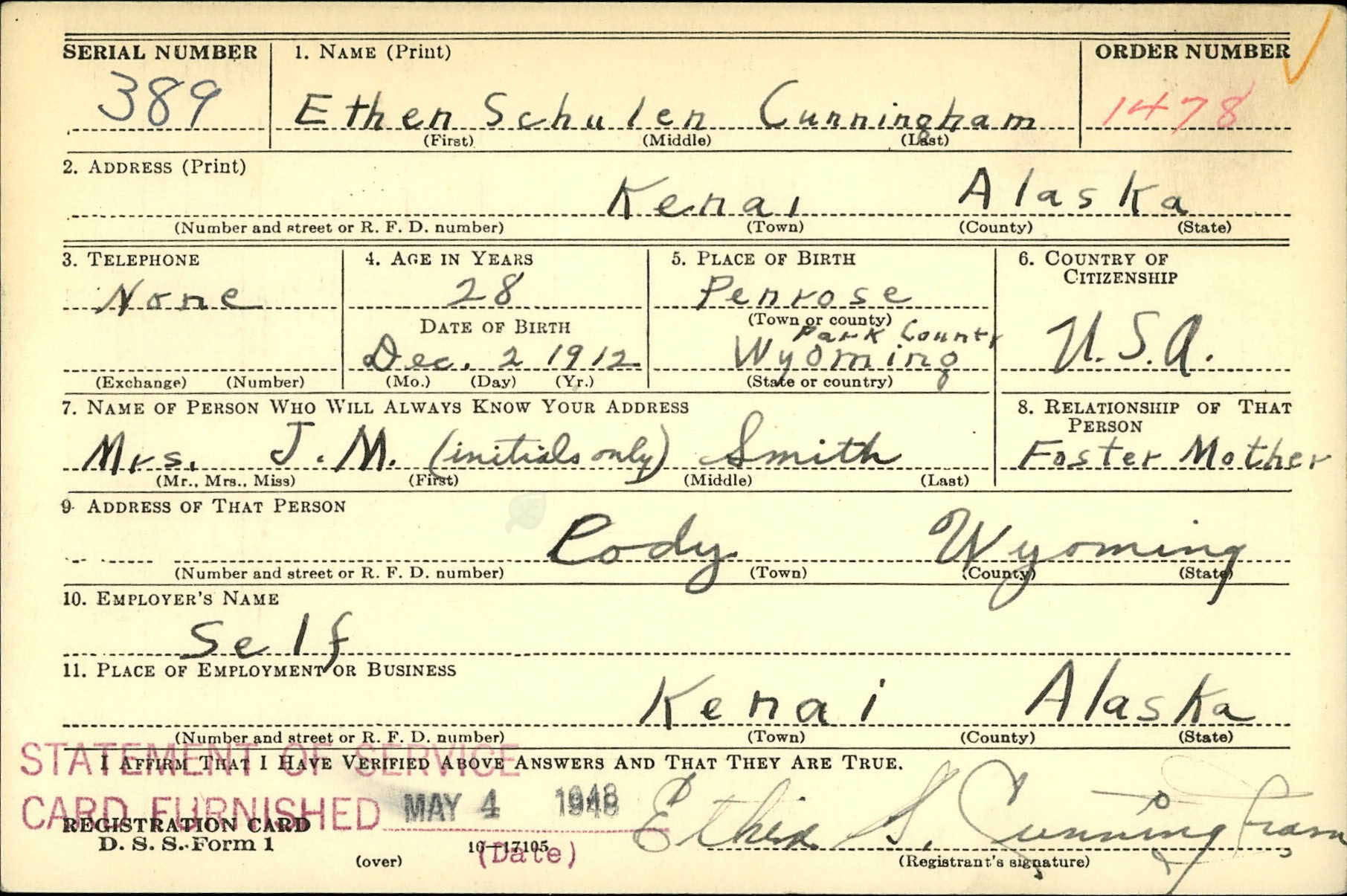

Ethen Schulen Cunningham’s first name had had different spellings over the years. For instance, the headstone on his grave now spells it E-T-H-A-N. So did his niece when she wrote about her uncle in a 1997 letter to the Kenai City Council. But when Cunningham himself signed his draft-registration card in Kenai on Jan. 22, 1941, he clearly wrote E-T-H-E-N.

Most of the documentation concerning Cunningham used “Ethen.” Whether that -en ending was an affectation or was given to him at birth is, at this point, anybody’s guess.

Cunningham was born Dec. 2, 1912, in Penrose, Wyoming, to parents James Robert and Sarah Jane (Moody) Cunningham. He had one older sibling, a brother named Bryan. A sister had died in infancy a year before Ethen’s birth.

Ethen’s mother died from acute appendicitis in early 1917 when Ethen was just 4 years old. For reasons that are unclear, Ethen and Bryan were no longer living with their father three years later when the 1920 U.S. Census was enumerated. Instead, they were in St. Ignatius, Montana, with their Uncle Theodore and his family.

In 1929, James Cunningham, then 54, remarried to Neomi Pearl Davis, who was 35 years old and had three daughters of her own. By the time of the 1930 U.S. Census, the two Cunningham sons were back with their father in Penrose, and sharing their home with Pearl and her girls. If family harmony existed at that time, it did not long endure.

By the time James was kicked to death by one of his own mules in 1935, the marriage to Pearl had already ended. His only named survivors were his two sons, both of whom were in their 20s. Interestingly, Ethen’s draft-registration card six years later would state that the one person who would always know his address was “Mrs. J.M. Smith,” a Cody, Wyoming, woman whom he referred to as his “foster mother.”

Cunningham was living in Kenai by February 1940, when the census-taker came around. He was 27 years old, he reported, and lodging somewhere unspecified. He was also calling himself a farmer. Later documents would call him both a commercial salmon fisherman and a writer. What kind of writing he may have done is unknown. Perhaps his writing career was more aspiration than reality.

More certain, however, is that he intended to make Kenai his home.

At the Land Office in Anchorage on Nov. 12, 1941, Cunningham filed on four adjoining parcels of land along the outside of a meander at about Mile 6 of the Kenai River. The parcels, totaling 100.88 acres, were located roughly northwest of Charles “Windy” Wagner’s property along that same river bend.

A very small, old cabin already stood on his property, and Cunningham moved in. According to Wagner, the roughly 10-by-12-foot structure had been built by Johnny and Arvie Wik, who later sold it to Mike Dolchok, who sold it to Ernest Lindeman, who then died in a moose-hunting accident.

By the time Cunningham arrived on the scene, said Wagner, the cabin itself — little more than a low-slung hunting shelter — was owned by Otto Schroeder, a friend of Lindeman’s. Cunningham agreed to purchase the building from Schroeder for $25 but never paid.

On Sept. 29, 1942, in Milwaukee, Wisconsin, Cunningham enlisted in the U.S. Army. After basic training, Private Ethen Cunningham was stationed at Fort Sill in Oklahoma. But his military tenure was brief.

After a February 1943 furlough to act as best man in his brother’s wedding in Sheboygan, Wisconsin, Cunningham returned to Fort Sill and was hospitalized a few weeks later. According to military records, he was treated for hemorrhoids and, more importantly, for a condition that kept him in the hospital for several months. Army doctors called this condition “dementia praecox, paranoid type,” and they determined that it had existed prior to his enlistment.

Dementia praecox is a now-outdated term indicating a chronic, deteriorating psychotic disorder that usually begins in the late teens or early adulthood. The term was later replaced by schizophrenia.

By July, Cunningham had been discharged from the hospital and from the service.

Although the record is sketchy for the next year and a half, it appears that Cunningham split his time between his homestead in Kenai and employment in Milwaukee. He was also drawn to Wisconsin in part by his interest in a woman that his new sister-in-law had introduced him to.

Martha Esther Sievers, an Army ordnance inspector, was born in January 1916 in Sheboygan. On Jan. 27, 1945, she married Ethen Cunningham in Milwaukee, where he was employed at the Allis Chalmers supercharger plant. According to a Sheboygan Press article about the wedding, the newlyweds would be heading in the spring to Alaska, where Ethen would be fishing commercially, as he had done since the early 1940s.

In early May, Ethen and Martha made the move north. One year later, Ethen began building a larger cabin to replace the bachelor pad in which he had been making his home. The Cunninghams didn’t know it yet, but a collision with the Franke family was on the near horizon — with fatal consequences.