Mary Mullen’s second collection of poetry, “A Thousand Cabbages,” improves on her earlier work and broadens her worldview through her powerful use of imagery and language, her more confident voice, and her tendency to look outside herself almost as much as she looks inward.

“My first book,” she said, “was powered by love. I was so in love with (daughter) Lily, her Down syndrome and all her remarkable smarts and potential. My second book has much more of the world in it: stress, anger, tough years of right-wing politics, reaching out, the perils of parenting alone and, I hope, plenty of hope and humor and love.”

Her first collection of poetry, “Zephyr,” was published in 2010 when Mullen, the youngest member of one of Soldotna’s earliest homesteading families, had been living in Ireland for 14 years and was the single mother of a 12-year-old.

The poems in “Zephyr” directed Mullen’s love at her childhood on the Kenai Peninsula, life in her adopted home in Ireland, and the surprise and delight of becoming a first-time mother at the age of 44. Now, Lily is 25 and living with her mother in Oregon. Mullen herself is completing her seventh decade, and the spread of years has allowed her to examine her life and times with a much more experienced eye.

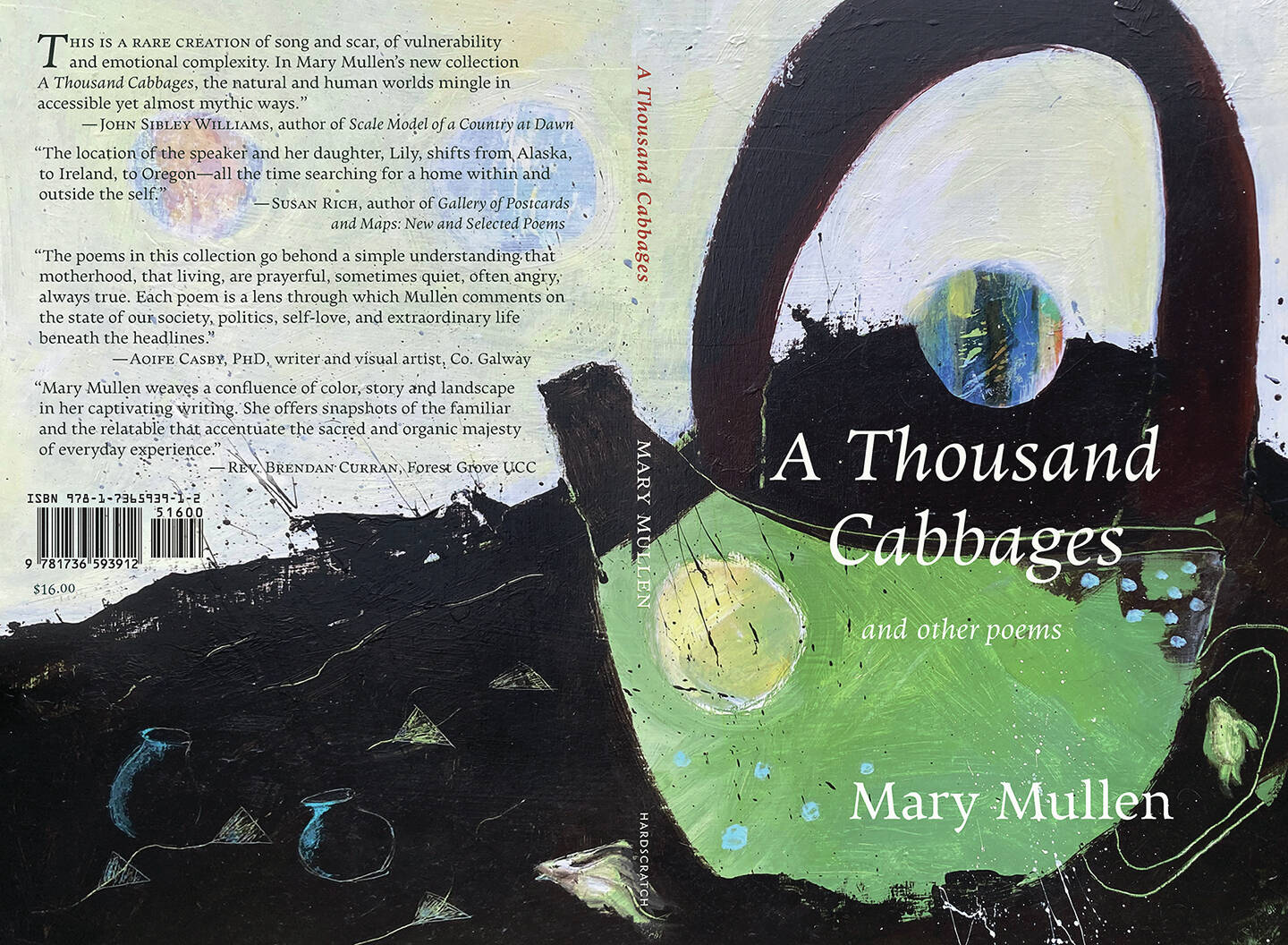

“A Thousand Cabbages,” dedicated to her sisters Eileen and Peggy Mullen and published in May by Hardscratch Press, contains 49 poems of various styles and is divided into three distinct sections: “Before Motherhood: Alaska,” “Single Motherhood: Ireland” and “Still and Always Mothering: Oregon.”

Across the sweep of this time and distance, Mullen touches on the things that have touched her — both personally and as part of society. Her poems praise diversity and kindness, the value of those who formerly occupied the same space, and the ability to think beyond one’s own needs and desires. And they stand firmly against discrimination and racism, bigotry and injustice.

The full title of the poem that gave rise to the title of the book makes clear many of those connections: “A Thousand Cabbages: Elegy for the house field we sold to Walgreen’s Pharmacy even though the land belonged to the Dena’ina People.”

The large field, cleared by the D4-Cat of D.C. “Pappy” Walker, was a major Mullen food source and one of its chief sources of income in the early days. Like the Kenai River that ran along their homestead, the field was a centerpiece of Mullen family life.

As a family, they pulled roots and stones, they weeded and fertilized, and they filled their root cellar for winter. They worked “until we imagined it broke our backs/ but it never did, the field just simply gave and gave.” It also changed over time: “Trees grew around the edge like the grey in our hair,/ Kenaitze hunters floated in misty amulets—”

Other poems in this section touch on the value of salmon, on early communications, on woodstoves and greenhouses, on Mullen’s educational career in remote villages and becoming part of life there, and on her elderly mother (soon-to-be 103-year-old family matriarch Marge Mullen) back on Lingonberry Lane.

In “Annie K’s Steam Bath,” she recalls crunching “over snow-packed hummocks” to crawl inside a scorching sauna in Kwethluk with some “Yup’ik beauties” who were delighted by this brave, overheated newcomer. “Annie K. touched my blotched skin. You need to eat more seal oil.”

When she wrote “Zephyr,” Mullen was part of a small community on the west coast of Ireland. In “A Thousand Cabbages,” her view of Ireland is retrospective.

“I Fell in Love with a Thatcher” notes the eyes and explores the motives of four individuals with whom she fell in love. The final and longest-lasting of these loves is her daughter Lily, and she reflects fondly on Lily’s “hail and jazz/ her shimmery salty air, her chance/ to shape love in the freshness of lily light.”

The adult Lily is still the apple of her mother’s eye, but in “The Elegance of Silk Scarves,” Mullen dips a toe in nostalgia concerning her daughter’s younger days. Each of the poem’s four-line quatrains begins with “I miss,” and the details demonstrate Mullen’s affection and her attention to detail, from “the bouquet of baby” to the “nappies heavy with sand,” from “the school girl who flew into my arms” to “the kitchen dancer, hipping and hopping silk scarves flowing in her whirlwind.”

Beyond Lily, the poems contain whimsy (“What Richie Havens and I Said at Campbell’s Tavern”) and even sorrow (“Off the Gentians” and “At Fenit Beach Decades after His Death”).

This section of the book ends with her departure from Ireland for a new life in Oregon and the keepsakes she carries with her, including “Lily’s umbilical cord/ hand print, age two/ unedited poems/ all those heart-shaped stones.”

Although the poems before the book’s final section contain some political moments, the Oregon-based poems offer much stronger commentary on current events and social trends. Mixed with verses viewing the world from Lily’s point of view, more thoughts on motherhood and thoughts about turning 70 are decidedly firm statements on the state of the nation and the world.

In “John Lewis’ OpEd Piece in the NY Times the Day of His Funeral and my Small Life,” she tracks civil rights leader and politician’s accomplishments across his life and compares them to her own, touching on Marvin Gaye, her own World War II Army Air Corps pilot father, and the deaths of George Floyd and Breonna Taylor in the process.

In “dear white nationalists, so called proud prayer oath boys,” she rails against the “baby boys” who went astray and wishes they could go back in time to find peace, instead of committing acts of hatred. “But you have no idea of redemption,” she writes, “… and I have completely lost any mercy I had/ for you my outstretched hand is now a fist to the sky—”

Elsewhere, Mullen finds a connection between the 1964 Good Friday Earthquake and the seismic upheaval of the 2016 presidential election. She invites Kamala Harris to do whatever she can to make the country a better place. She also comments on toxic masculinity and the Russian attack on Ukraine.

The collection concludes with a series of deeply personal poems that delve inward. These poems include titles that reveal the poet’s mind-set: “Instructions for Loving Me,” “Someday I’ll Love Mary Mullen,” and the finale, entitled “Checklist for Becoming a Septuagenarian.”

All of the poems in this slim volume are rife with color and light, vibrant life and bright, clear details — all aspects that drove the engine of her first collection and now drive her second, with the same amount of heart and passion, but perhaps with greater wisdom.

“I did not know much about poetry in 2010,” Mullen said. “I was a student of poetry. Perhaps now I am an apprentice. A journeywoman. It’s a remarkable art, and I am humbled by it.”

“A Thousand Cabbages” is available at River City Books in Soldotna or can be purchased directly from the publisher at www.hardscratchpress.com. Mary Mullen is scheduled to do a reading of her poetry June 18 at River City Books.