AUTHOR’S NOTE: The two most deadly years for people on or near Tustumena Lake were 1965 and 1975. This series examines the tragedies of those two years. A similar version of this story about a 1965 Cordova Airlines crash into the lake first appeared in the Redoubt Reporter in April 2012.

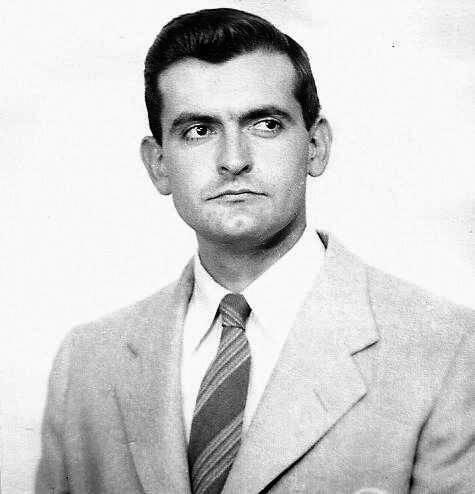

Staying alive seemed unlikely, but Harold Galliett bucked the odds.

Even in the summertime, the silt-laden waters of Tustumena Lake are notoriously cold. Fed by mountain streams and the Tustumena Glacier, the surface temperature is regularly in the 40s, greatly increasing the likelihood of hypothermia and greatly reducing the likelihood of survival. Tustumena Lake has claimed many drowning victims over the years, but it failed to claim Harold H. Galliett, Jr..

On Sept. 4, 1965, Galliett and four other individuals abandoned a rapidly sinking commercial airplane, and he alone was able to swim more than a mile to shore and survive.

The aircraft was a 42-foot Aero Grand Commander operated by Cordova Airlines pilot Bob Barton. With the lake that day as flat and smooth as glass and the cloud ceiling only 300 feet high it is likely that Barton, struggling to distinguish air from water, flew the plane right onto the surface of the lake, where it came to rest about a mile from the northern shore and sank in a matter of minutes.

On board besides Galliett and Barton had been Port Graham residents Antonio and Martha Cuerda and Nikiski construction worker Raymond M. Puckett. Then they were all in the water — all but Barton supported by seat cushions for flotation — sometime around 9:45 a.m. The air temperature was approximately 50 degrees, and the upper layer of water was likely between 40 and 50 degrees.

Less than five minutes after contact with the lake, their plane had vanished, drifting toward the bottom of the lake nearly 140 feet below their churning legs.

Galliett, in his statement to authorities shortly after being rescued, said that he had placed his seat cushion beneath his left arm and begun to swim the side stroke to conserve his energy. After he had swum only about 100 feet, he said, he heard Puckett yell. Galliett turned to look and saw the 27-year-old man sink out of sight.

Galliett’s leather dress shoes began to swell in the water and hindered the effective kicking of his feet. He tried to tread water and remove his shoes, but he struggled to remain afloat, so he left them on and continued swimming.

The next time he looked back for his fellow passengers, he noticed that the Cuerdas were still moving toward the shore but the pilot had vanished. Before he was halfway to shore, the Cuerdas, too, were gone.

All alone on a 26-mile-long glacial lake, Galliett continued his measured breathing and steady stroke, watching the bubbles from his exhaled breaths trail behind him, counting the seconds it took them to move past, and calculating the speed at which he was moving. With a waterproof Wittnauer watch — a gift from his father — he occasionally checked his time, relying on years of swimming practice to gauge his progress.

When Galliett had attended the University of California in the 1940s, he had been financially strapped and forced to live in the basement of a boarding house occupied by numerous other young men, all of whom would crowd into the single upstairs bathroom each morning. “I couldn’t get in,” he said. “So that got kind of bothersome after a while. I said, ‘Well, hell with this. I’m going to go down to the gym.’”

At the UC gym each morning, he stood beneath the shower, with all the hot water and elbow room he desired, and washed himself and shaved. After a while, however, he discovered that the university had an Olympic-sized swimming pool right outside of the showers, and he decided to add a workout in the water to his time at the gym.

“I figured out how many laps I needed for a mile, and I decided to swim a mile every day,” Galliett said. “And that’s what I did. And I kept it up for several months.”

He had enjoyed swimming since his childhood, especially in the days that he and his family had lived on Oahu. “My mother used to pack us into our old Studebaker, and we’d roll on down to the beach, and I’d be there all day, swimming and trying to surf and whatnot,” he said.

The UC pool and the Hawaiian surf, however, were considerably warmer than the frigid waters of Tustumena Lake, which began to exact a toll on Galliett as he continued to move almost mechanically shoreward. Despite his exertions, his legs grew numb and his strength waned.

About 45 minutes into his swim, he heard the drone of an airplane, and shortly thereafter he saw a Cordova Airlines Widgeon fly over in a southeasterly direction.

“I tried to wave to attract their attention,” he said, “but every time I would put my arm up to wave I would start sinking, so I thought I better give that up and just try to keep swimming.”

Soon, he said, he noticed that the shoreline was only about 100 feet away, and as he drew closer he felt his feet begin to strike the bottom of the suddenly shallower water.

“I just swam right into the shore,” Galliett said. “I was very cold. I just flopped on the beach and (was) out of breath and almost unconscious. I tried to move and just couldn’t even do that for a while. In fact, I couldn’t even move the cushion.” The time was approximately 10:45 a.m.

He lay there for perhaps a quarter of an hour before he was able to stand and try to walk. He saw a point of land about 50 feet away to the west and began moving down the beach in that direction. From the point, he peered into a small bay and noticed the reflection of what appeared to be metal. On the theory that he was seeing the roof of a remote cabin, he set off with the hope of shelter.

“I was staggering,” he said. “To walk, I had to keep my feet far apart so I wouldn’t fall over sideways.” The cabin was nearly a mile further westward, and along the way Galliett foraged on lowbush cranberries. He also saw several spruce grouse and considered trying to bash one over the head with a stick; instead, unwilling to make the effort to hunt, he drove himself forward.

He arrived at the Pipe Creek Cabin just as he was “beginning to feel kind of alive again,” he said. He unwired the front door and walked in. Inside, he saw a woodstove in one corner, two cots with mattresses in another corner, and, above the stove, a small shelf containing an old-looking can of milk, a can of coffee grounds, and a bottle filled with long-handled kitchen matches.

“I thought, ‘Oh, I got it made now. I’m not even going to be cold tonight. I can put one mattress on top and sleep on one,’” Galliett said, “I didn’t start a fire in the stove. I decided to do it outside. I was going to pull a Robinson Crusoe or something like that — build a fire and have a lot of green wood to dump on it (to make a signal).”

For tinder he employed dry twigs and pages from an old American Rifleman magazine, and soon he had a roaring fire. Then, with the help of a saw from the cabin, he stacked armloads of green branches nearby. He stripped down to his underpants and lay his wet clothing and the contents of his wallet out to dry a safe distance from the fire.

Sometime after noon, he heard another aircraft.

“I was walking around in my shorts, so I grabbed my shirt, dashed down to the beach and started waving my shirt,” he said. “A Cordova (Airlines) C-46 flew over me then, and came back and passed over me about five or six times. I kept waving my shirt and practically jumping up and down, (but) the C-46 didn’t even tip his wings or anything, and he left.”

Shortly afterward, however, the amphibious Widgeon returned, landed out on the lake, and taxied in to shore. The pilot hollered for Galliett to climb aboard, but Galliett said he needed to go back and collect his belongings, extinguish the fire and close up the cabin first. Behind him, the flames were reaching at least 15 feet toward the sky.

The pilot told him to grab his stuff but not worry about the rest. Someone else would take care of the details, he said.

Inside the Widgeon a few minutes later, Galliett received dry clothes, which he slipped into as they taxied out to the area he indicated as the crash site. There they found a rainbow-like sheen of gas and oil, but no bodies, no debris, no cushions.

Galliett was back at work in a few days. His ordeal and rescue were reported in the local Cheechako News and in the Anchorage Times, and later that fall the Grand Commander was salvaged from the bottom of the lake. The bodies of neither the pilot nor the other passengers were ever found.

“I’ve told this story a few times,” said Galliett in 2012, via telephone from his home near Oroville, California. “It didn’t bother me at the time (because) I felt so lucky to have survived. Who am I to criticize the decisions of the Almighty? Anyway, I made it out. That’s all I can say, really.”

Galliett died in July 2014. He was 90 years old.

The Grand Commander was last registered in the United States in 1968 and then was exported to Canada. A Canadian accident report from 1975 describes the aircraft, then operated by a company called Harrison Air, crashing — without casualties this time — in Vancouver. Since information about the plane ends there, it was probably scrapped, this time for good.