AUTHOR’S NOTE: The two most deadly years for people on or near Tustumena Lake were 1965 and 1975. This series discusses the tragedies of those two years. In chronological order, the final four chapters of this series examine the four accidents and the seven lives lost in 1975.

The worst year for recorded fatalities on or in the vicinity of Tustumena Lake was 1975. In June, one man died in a firearms incident. In July, two men were killed when a single-engine plane crashed in the mountains southeast of the upper end of the lake. In August, three individuals drowned while attempting to cross the lake at the end of a hunting trip. And in September, another man drowned while trying to retrieve a drifting skiff.

Four tragedies in four months. Seven lives lost —the same number of fatalities recorded in the entire previous decade, including the four deaths in the 1965 Cordova Airlines crash into Tustumena Lake.

Nightmare Ending

On Wednesday, June 13, 1975, Kerri Dolph, in a 12-by-12-foot shed constructed of peeled spruce logs, was sitting before a glassless window and staring vacantly out at Tustumena Lake when she noticed two men in a small boat, powered by an outboard engine, turning toward her location. As the men came ashore, she rose from her perch at the window and hurried to the lake to greet them.

The first thing she told them was: “My husband is dead.”

He had been dead for five days.

Besides her husband John, Dolph had seen no other people since June 7, when a Kenai floatplane pilot had dropped off her and John at a campsite just east of Indian Creek, which flows into the lake from the Kenai Mountains.

After John died, Kerri had used logs to create an S.O.S. sign on the sandy lakeshore. Next to the sign, she had erected three-foot piece of driftwood and pinned to it a white T-shirt to act as a flag. The two men — Archie Ramsell, of Cohoe, and Dick Moll, of Kenai — had spotted her plea for assistance while motoring up the lake.

“One gentleman,” she recalled recently, “asked that I stay there with the other guy, and (he) went into the (shed) and came back out with my coat and just very kindly led me to the boat and took me somewhere.”

That “somewhere” was Ramsell’s home, where Ramsell called the Ninilchik post of the Alaska State Troopers and reached Officer Roy Sagraves. Before Sagraves headed to Cohoe to interview Ramsell and Dolph, he called Trooper Thomas A. Sumey of the Soldotna post and requested that he travel immediately to Tustumena Lake to investigate the scene.

Sumey enlisted the aid of former Kenai lawman Phil Ames, who met him at the Kasilof River boat launch and took the officer in his 20-foot river boat to Indian Creek.

After Kerri Dolph was interviewed by Sagraves, she was taken to Central Peninsula General Hospital, placed on an I.V. drip and kept overnight. She had lost 15 pounds from her slim frame and was severely dehydrated and in shock.

The next day, she was reinterviewed by Troopers. Then, although she and John had driven to Alaska from their home in Colorado, “someone,” she said, “put me on a commercial flight back to Colorado, and then I think a relative flew to Alaska and got our gear and drove our car back.” John’s body was on the same flight home, but she was not told that until later.

When she arrived in Denver, at least a dozen family members were waiting at the airport. She was momentarily confused by all the attention. “The stewardess,” she recalled, “told my mother I had slept the whole trip, whimpering in my sleep.”

The shock caused by the trauma she had experienced took months to wear off.

“I went back to the home of my youth (Nebraska) and lived with my folks for a little over a year before returning to live in Colorado,” she said. “Shock is a lovely thing, if you think about it.”

Promising Beginning

Both Kerri Lynn Chenoweth and John Donald Dolph Jr. had experienced brief, unhappy marriages before they met. Dolph had been married for about three years, and Chenoweth closer to three months. Dolph had a young daughter — age 4 at the time of the Alaska trip. Chenoweth had no children.

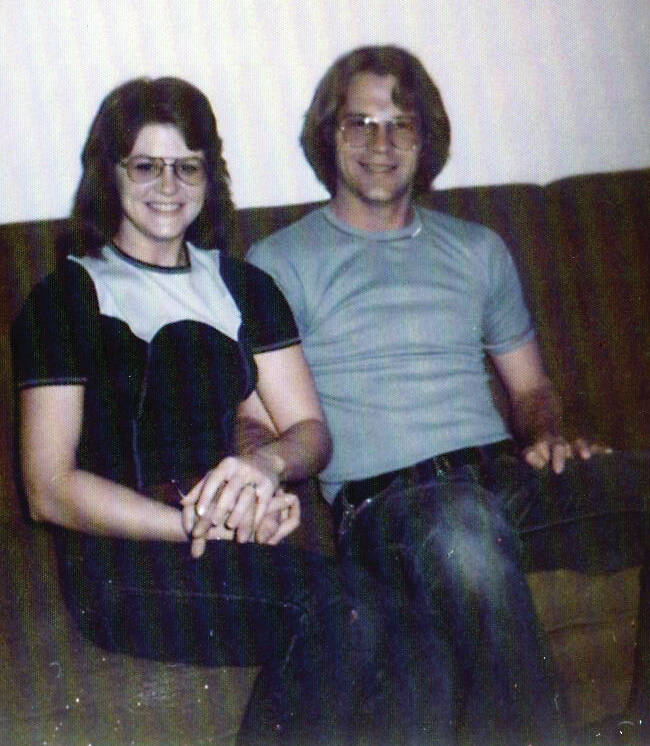

They married in the Church of the Nazarene in Thornton, Adams County, Colorado, on Nov. 30, 1974. “John always wanted to go to Alaska,” Kerri said, “so we (planned) a ‘delayed’ honeymoon the following year in June.” On the day they were flown to Tustumena Lake, Kerri was 21. John, a U.S. Army veteran, was 29.

“The plan was to tent camp,” Kerri said. “The presence of a cabin (there) was just a coincidence.”

She was referring to a two-story log cabin built in 1933 by Emil Berg and owned in 1975 by Kasilof residents Ray and Lorraine Blake. Berg, younger brother to renowned hunting guide Andrew Berg, had died in 1953. Berg had also constructed on his five-acre inholding a log barn and the log shed in which Kerri had been sheltering before the arrival of her two rescuers.

John Dolph had carefully planned this honeymoon adventure. Using a large-size, small-scale U.S. Geological Survey map, he had carefully drawn (and shaded with colored pencils) his own map of Tustumena Lake, showing several of the main streams flowing into the lake, the Kasilof River flowing out, and a half-dozen of the structures he had determined to exist around the lakeshore.

East of Indian Creek on John’s map, he had penciled an X and written “X marks the spot.” From that X, he had drawn a dotted line, denoting either a trail or a route, along the back perimeter of Tustumena’s glacial flats over to a second “X marks the spot” just north of the Tustumena Glacier River and a cabin known as the Cliff House.

It may be that John had intended at some point to move their camp. He had arranged with the floatplane pilot to pick them up 21 days after dropping them off, so they had plenty of time to explore.

“I know he (also) wanted to pan for gold,” recalled Kerri, “but just as a ‘visiting-Alaska-sorta-thing’ to do.” Indian Creek had received plenty of gold-mining attention over the preceding decades, and some attention had also been paid to streams in the vicinity of the glacial flats.

To Kerri, John had a better sense of the lake than the pilot they had hired. “John knew where he wanted to go,” she said. “He had to tell the pilot where to drop us, but a cabin there seemed a pleasant surprise to both of us.” The Emil Berg cabin (known then as “Blake’s Place”) was not marked on John’s own map.

After they arrived at the lake, they chose to pitch their tent, despite the proximity of the cabin and outbuildings. Perhaps they did not wish to impose their presence on whomever the cabin owner might be. Perhaps John felt that staying in a cabin would somehow tarnish the spirit of the adventure he had so carefully planned.