AUTHOR’S NOTE: As a child I accompanied my father up the Russian Lakes Trail more than once. In a clearing near the lake outlet — just off the trail, above Russian River falls, and inside the boundary separating the Chugach National Forest from the Kenai National Wildlife Refuge — I found Icelandic poppies growing in streamside gravels and what appeared to be part of a cabin foundation. Only recently, I learned the story behind this place.

Rebuilding

Luther W. Bishop and Fred Broadwell were awakened on a mid-October morning in 1930 by the sound of rifle cartridges popping and the sight of flames raging all around them. Outside, hot tar dripping from the roof burned them as they tried desperately to extinguish the fire consuming Bishop’s new, two-story hunting and fishing lodge.

Their efforts were in vain. The blaze soon leaped to Bishop’s old lodge and residence, leaving both structures little more than piles of ashes and blackened timbers. Gone were Bishop’s rifles, his fishing tackle, his boots and clothing, all his personal effects, and the source of his summer income.

Besides the clothes the two men had been wearing as they fought the fire, they managed to save only a single mattress, Bishop’s Victrola, the land surrounding his dwellings, and the penned foxes that he had been raising on this location since 1922.

Bishop had spent two years building his new 26-by-26-foot lodge on Russian River, near its outlet from Lower Russian Lake. Broadwell, of Seward, had been on-site for several days, completing the interior decorating that would allow the place to be ready for a grand opening the following spring.

In fact, Bishop had moved into his new lodge only three days earlier.

But when he and Broadwell arrived in Seward on Oct. 16, he was already determined to build again.

The following day, the Seward Daily Gateway began an article about Bishop’s loss this way: “A misfortune that will be equally mourned by many sportsmen both here and abroad has overtaken Lew W. Bishop, ‘Prince of Hosts’ of the world-famous Russian River, the home of the big trout.”

The newspaper said Bishop’s lodge was “internationally known” and opined that there would now be “an international lodge of sorrow.” But it added that, already, “several of the local boys are trying to dope it out so that they can get away from their duties here for awhile and devote some strong-arm effort and other needful assistance in the new building operations.”

By the spring of 1931, a new two-story log building — the lodge’s third iteration — stood on the old site, ready for business. A newspaper announcement concerning the grand opening noted that one of the previous year’s guests — Gen. Robert E. Wood, president of Sears, Roebuck and Company — boasted that the Russian River was “the finest fishing stream in the world.”

Origins and Endings

Many parts of the history of Luther W. Bishop have been obscured by the passage of time and the inconsistency of record-keeping practices, so holes in the story do exist. Some of the basics are clear, however: Bishop was born in Ionia, Michigan, in 1873. By about age 25 he was a private in the Michigan 35th Infantry, Company C, embroiled in the Spanish-American War.

By at least 1920, Bishop was in Alaska. He was listed in the U.S. Census that year as a resident of McGrath, as a single man, and as a placer miner. Shortly thereafter, he came to the Kenai Peninsula.

According to former state historian Rolfe Buzzell in “The History of Cooper Landing Settlement Patterns,” Bishop began raising foxes as a fur farmer at Lower Russian Lake in 1922 and probably received his U.S. Forest Service permit for this operation in 1921. Ten years later, Bishop’s permit was changed from fur farming to residential and remained that way until 1938 when he departed the area.

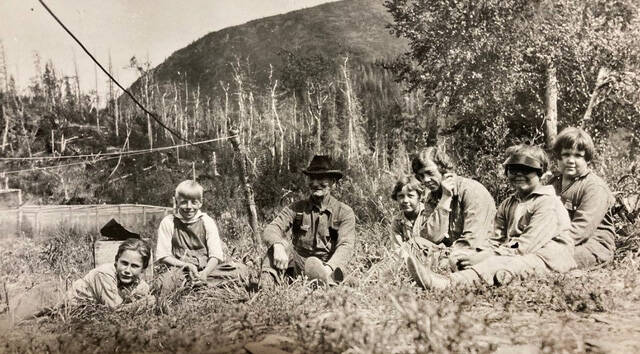

It is difficult to say when precisely the fur farm at the lake began to double as a lodge for aspiring hunters and fishermen. The Seward newspaper referred to Bishop in 1923 only as a “fox rancher,” but by 1928 the paper was already calling him the “prince of hosts.” A September article that year referred to “the big influx of visitors each season” at the “noted fishing and hunting resort,” making it necessary for him to expand the size of his accommodations.

In January 1930, the Seward paper referred to the lodge as “Bishop’s Place.” And only days before both his old and new lodges burned to the ground, a Forest Service survey noted that the land between the Snug Harbor side of Kenai Lake and the Forest Service boundary at Lower Russian Lake contained 17 habitable dwellings, including Bishop and five Cooper Landing men who were fur farmers.

After the fire and the rebuilding effort, Bishop’s new two-story lodge seemed to get more press than ever. One story detailed Bishop’s method for catching salmon from the falls to feed both his foxes and his guests. Another related the story of “Tootsie,” a black bear cub he kept on a running line for the entertainments of visitors.

The biggest news concerning Bishop’s Place, however, may have come just before the fire, when the U.S. stock market crashed and the Great Depression got under way. Depression-era economics sounded a death knell for the fur industry, which had relied primarily on luxury purchases that most Americans could no longer afford.

As a result — despite having about 30 foxes by the end of summer 1931 — he told the Seward Daily Gateway that he was considering pelting (killing and skinning) the animals that autumn and concentrating solely on his wilderness lodge.

According to the third volume of Mary J. Barry’s Seward-history trilogy, Bishop sold his lodge in 1937 to Harry L. Smith, a Moose Pass teacher who renamed the business the “Russian River Rendezvous” and opened it for business under that name in the summer of 1938. The new Forest Service permit granted to Smith referred to him as a resort owner.

Only two years before he purchased the lodge from Bishop, Smith’s 9-year-old daughter, Fannie Lou, had been killed while walking to Cooper Landing after a day spent fishing on the Russian River.

When Fannie Lou, her sister Jorene, her mother Eunice and some other locals were returning from their outing at dusk and were rounding the bluff above Schooner Bend, a boulder described as weighing about 40 pounds hurtled down the mountainside, deflected off a larger boulder and struck Fannie Lou directly on the forehead, “crushing and fracturing her head,” according to a news report.

In 1938, Smith had to hope that his luck was changing for the better.