AUTHOR’S NOTE: I would like to thank Peggy Arness for access to her history files and the Resurrection Bay Historical Society for access to its archive of old Seward newspapers. It would been impossible to tell this story this fully without their support.

In late July 1958, near the end of the commercial sockeye season on Cook Inlet, Jimmy Johnson took time out to do a little offshore partying.

According to a news report three days later, Johnson’s drift boat, the Tony, was tied up to the fishing vessels Gulf Stream and Ceylon and was anchored in front of the Kenai Packers cannery on the lower Kenai River.

At the party with Johnson on the Gulf Stream were its operators, Walt and Bed Soule, plus Walt and Kathy Johnson from the Ceylon. At some point, Jimmy Johnson, almost certainly intoxicated, attempted to return to the Tony but failed to properly navigate the transition.

From the Anchorage Daily Times on Aug. 2: “The four (other partiers) stated that as Johnson was leaving the Gulf Stream he missed his skiff and stepped into the water. … He disappeared and was not seen again.”

His body was retrieved nearly three weeks later, apparently tangled in a gillnet on Salamatof Beach north of Kenai. He was buried on Sept. 3, and news reports and gossip at the time offered only convoluted and partial notes regarding his personal history.

In fact, there was general agreement on only these four things: (1) Despite his ignominious demise, Jimmy Johnson had been immensely skilled with watercraft of all kinds. (2) His bravery and skill more than a decade earlier had helped save at least 100 shipwreck survivors. (3) His nickname had been “The Screaming Swede.” (4) He was a loud and raucous partier and heavy drinker.

The Search

James William “Jimmy” Johnson had done a lot of living in the 38 years before his death, and he had left a lasting impression on many lives he touched along the way. One of the admiring individuals whose path he had crossed was James Victor “Jim” Arness, of Nikiski.

During World War II, Arness and Johnson had both been members of the U.S. Army’s harbor craft company operating between Resurrection Bay and the Aleutians, tasked with captaining power barges to ferry cargo from freighters and transport vessels. It was difficult, demanding work in waters that were often stormy and in many cases poorly charted or not charted at all.

In the late 1990s — more than a half-century after the conclusion of the war — Arness, then in his 70s, began a quest to find the grave of his old friend.

He knew how and where Johnson had died, and he began his search with the premise that Johnson had been buried in Kenai. However, the two James Johnsons listed in the Kenai Totem Tracers’ “Cemetery Inscriptions and Area Memorials in Alaska’s Kenai Peninsula Borough” failed to fit the criteria Arness was looking for — first and foremost, a death date of July 30, 1958.

City of Kenai officials confirmed his findings: The Jimmy Johnson he sought had not been buried in Kenai or anywhere else on the peninsula. Where, then, were his friend’s remains?

Jim Arness was a man not easily dissuaded. He wrote letters. He read clippings from old newspapers. He made numerous inquiries and dug around until, by 2001, he had uncovered the answers he sought and was prepared to do something about the answers he didn’t like.

Johnson’s home at the time of his death had been difficult to pin down. The Anchorage Daily Times at the time of his death said he was “from near Cordova and is survived by his wife, Annie Ponchee. It is believed he had a daughter living in Sitka.” Johnson’s death certificate, however, listed him as “divorced,” and a Times article about his burial stated that “none of Johnson’s family lives in Alaska.”

Elsewhere, he was said to be a resident of Seward and Seldovia. There was also a mention of a home in Kodiak.

In recognition of Jimmy Johnson’s shipwreck heroism in 1946, the Alaska Steamship Company had made the arrangements and footed the bill for his funeral, which had been set for Anchorage, with the burial in Angelus Memorial Park.

After the body was recovered in mid-August, U.S. Commissioner Stanley F. Thompson had signed a permit allowing it to be transferred by the Territorial Patrol of Alaska from Kenai to Anchorage.

In 2001, more than 40 years after Johnson’s burial, Arness was dismayed to learn that Johnson’s remains lay in an unmarked grave.

Arness had envisioned a marker denoting Johnson’s military service, with a special notice concerning the lives he had saved. Instead, the identity of the individual buried in Space 180, Lot A3, of Devotion Garden in Angelus Memorial Park, could be determined only through cemetery record books.

Arness determined to rectify the situation.

A receipt issued by the cemetery on Aug. 6, 2001, shows that Arness used personal check #1320 to purchase a $940 bronze plaque (and pay other, lesser expenses) to adorn the gravesite of James William Johnson.

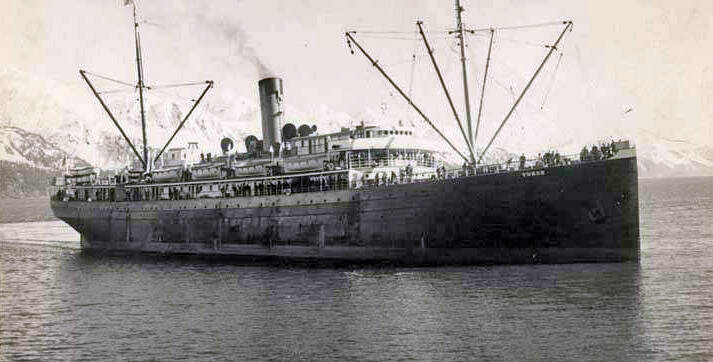

The plaque — illustrated with an oval portrait of the ship whose passengers Johnson had helped to rescue, but also containing factual errors — says:

SGT. JIMMY JOHNSON “THE SCREAMING SWEDE”

HARBORCRAFT U.S. ARMY ALASKA

OCT. 5, 1919—JULY 30, 1958

CAPTAIN OF BSP511 (ARMY), A HERO TO 400 PASSENGERS AND CREW

ABOARD THE STEAMSHIP YUKON WRECKED EAST OF SEWARD JAN. 26, 1946

The Wreck of the S.S. Yukon

Officials noted scattered snow squalls in some portions of Resurrection Bay at 4:20 p.m. on Feb. 3, 1946, when the steamship Yukon left the Port of Seward and set sail for Seattle, with stops scheduled in Valdez and Cordova. On board were 496 individuals — 372 passengers and 124 crew members, including a number of military personnel and civilians from Fort Richardson in Anchorage.

Skippered on this day by Captain Christian E. Trondsen, the S.S. Yukon was a common sight to Sewardites, having made its initial voyage to Alaska in late May 1924. Built in Philadelphia in 1899, the Yukon measured 360 feet long and 50 feet wide. It weighed 5,746 tons and had an estimated value of $1.25 million.

Like many of the service members aboard on Feb. 3, the ship had played an important role in the recently concluded world war. It had been requisitioned, along with 16 other Alaska Steamship Company vessels, by the War Shipping Administration and had been repainted gray as camouflage during its tour of duty. In fact, it was still under government control and still painted gray at this time.

The weather worsened severely as the ship exited the bay and headed for Prince William Sound. Winds intensified, and blowing snow greatly reduced visibility. Capt. Trondsen found it increasingly difficult to navigate and be certain of his coordinates. He knew it was possible that the ship had been blown 3 to 7 miles off course.

To alert other vessels they would be unable to see in the storm, the crew sounded the ship’s whistle every few minutes. Then, just after 4 a.m., the S.S. Yukon struck rocks off Cape Fairfield on the western side of Johnstone Bay, west of Montague Island and about 10 miles from Cape Puget — approximately 35 miles east of Seward.

Informed that the ship’s hull had been breached, Capt. Trondsen ordered the Yukon to be beached. He hoped that driving the vessel higher onto the rocks would stabilize it and prevent it from sinking.

A distress call from the Yukon was received in Ketchikan, Kodiak and as far away as Honolulu, and was relayed across the Territory via the Alaska Communication System. The distress call indicated that the captain was uncertain of his position, that his ship was aground, and that the vessel was being hammered by huge, icy waves.

But his situation was even more dire.

At some point during the night, the S.S. Yukon began to break in half.