AUTHOR’S NOTE: In late 1948, after six months of homestead living on the central Kenai Peninsula, Rusty Lancashire wrote home to her folks in Illinois. She noted that some people who had arrived at about the same time they had were already pulling up stakes. She and husband Larry, however, were in it for the long haul: “Larry and I may be dopes to live like this,” she wrote, “but we love it.” They lived on their homestead for the next five decades.

Rusty Lancashire hadn’t allowed her first impressions of Kenai in 1948 to deter her from making the central Kenai Peninsula her home: “Kenai looks like a ghost town,” she had told family in the Lower 48. “You’re through it before you know it. There’s a general store, church, bar and post office.” That was all she noticed at first.

Later, she got a look at the old territorial school, which she described as “much too small and … a fire trap.” A few months later, she offered a more detailed assessment:

“It is a sad thing a country like the United States lets her territories degenerate so…. Seventy students from the first grade through high school share four rooms (with three teachers). The furnace has been so broken down (that) when the weather is cold the children have to wear their coats—parkas—mukluks, and all. That isn’t the most serious thing. All the beams are rotted, and the building is about to fall.”

If a new school wasn’t built soon, she said, she’d have to consider correspondence courses for her three daughters. Fortunately for Martha, Lori and Abby, a new school was in place by the early 1950s, and Rusty was happily directing high schoolers in a play there.

The promise of progress and opportunity in their new homeland kept Rusty and Larry engaged back then — and did so for the rest of their lives.

Martha graduated as valedictorian of Kenai High School in the spring of 1961 and went off to college that fall. Lori finished high school three years later, and Abby graduated two years after that.

While Martha was still away at college, and just before Lori departed for nursing school in the fall of 1964, Larry and Rusty decided to try a new venture.

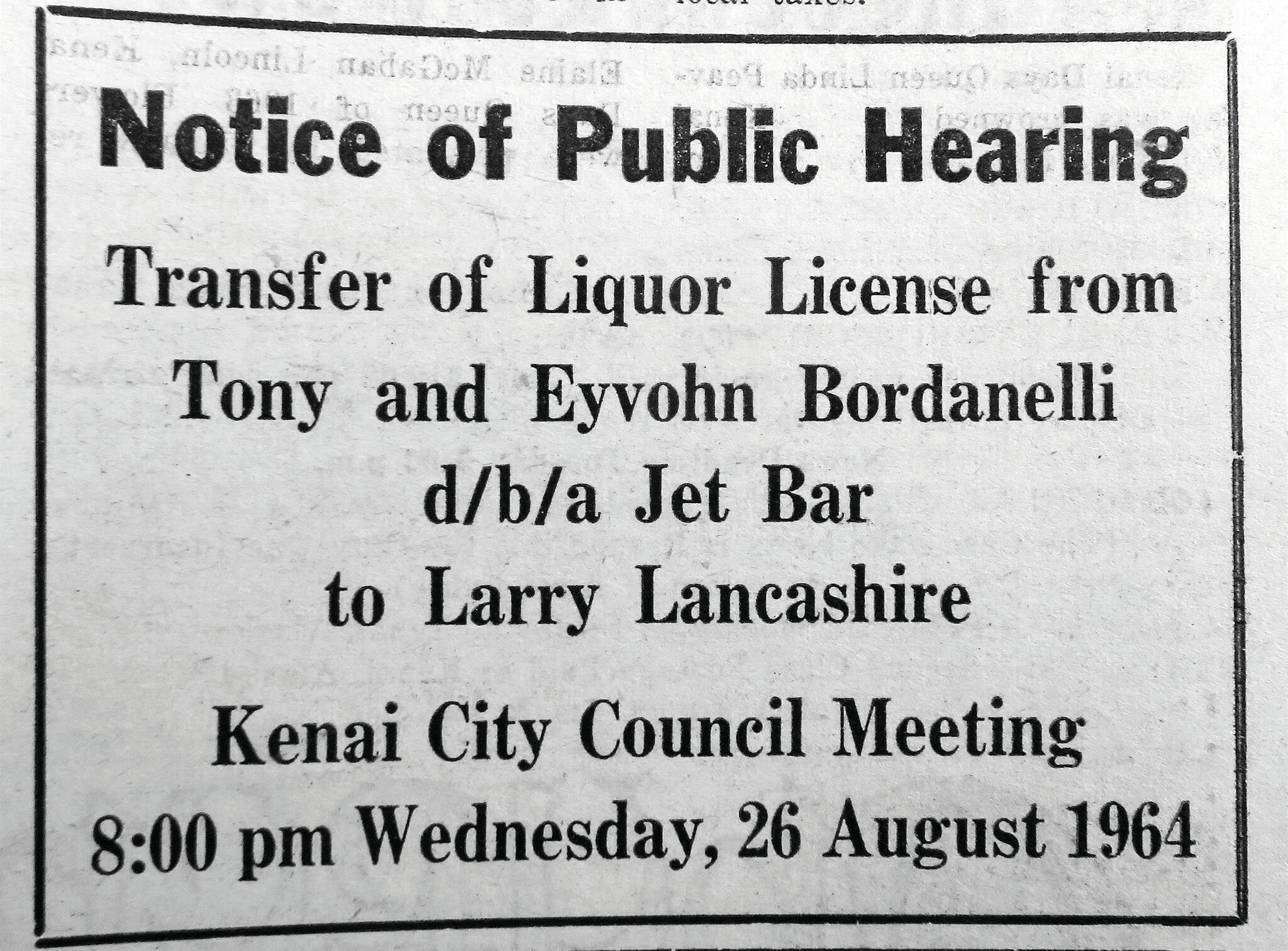

Just north of Kenai stood the Jet Bar, owned and operated by a colorful character named Tony Bordenelli, who, only a few years earlier at the Sky Bowl in Soldotna had set a new world for the number of consecutive games bowled. Bordenelli and his wife Eyvohn were ready to move on, and the Lancashires decided to take the plunge.

Larry Lancashire acquired the Bordenellis’ liquor license after a Kenai City Council public hearing in late August 1964. Shortly thereafter, Larry’s Club, a dining-and-drinking establishment, was born.

“Dad (used to say that he) had homesteaded 17 years and was $17,000 in debt,” Martha said. “He bought the bar and was out of debt in a year or two. Mom was a good cook, and Dad did a lot of bartending.”

One of the downsides of the demands of the new business, said Lori, fell on Abby, who was still in high school and disliked having her parents gone so much.

Martha earned money at Larry’s Club as a cocktail waitress for a couple of summers while she was on break from college. She worked only on days when her father was also on the job, she said, and she liked that Larry’s presence meant she was accorded with respect.

Of course, running a restaurant and bar was not always peaceful.

On Oct. 12, 1968, Lori, who had returned home after completing nursing school, was sitting in Larry’s Club, having a drink and chatting with another woman, when a patron named Arlon E. “Jackson” Ball came up to her.

“Go find your mother,” commanded Ball. “She’s shooting pool at the Rig Bar.” Lori said it didn’t occur to her at first that Ball was attempting to get rid of her. He knew trouble was brewing. Lori initially refused to go, but Ball was persistent. He told Lori to leave and to take her friend with her to the Rig.

Later, as they sat at the Rig, watching Rusty shoot pool, the truth dawned on Lori. “I saw a cop car drive by—red lights and siren,” she said. “I told Mom, ‘Come! They’re going to Dad’s!’ We got there, and Jackson Ball had been shot and was dead on the floor.”

A man named Jerry Thomas Edwards, responding to a scuffle involving his brother Larry Edwards outside the bar, had shot Ball inside. Before law-enforcement authorities arrived, Larry Lancashire had managed to take Jerry Edwards’s .38-caliber revolver away from him and then attempted to calm him down.

Ironically, Alaska State Trooper David Ulfers, the first officer to arrive on the scene, later proposed to Lori and became Larry Lancashire’s son-in-law.

Troubles such as the shooting of Jackson Ball were, however, not enough to dissuade Rusty and Larry from making a similar purchase when another watering hole became available in Soldotna. When the former Davenport’s, former Ace of Clubs and current Maverick Saloon came up for sale, the Lancashires found themselves the owners of two bars in two separate towns.

They ran both establishments successfully for many years, and they were still owners of the Maverick when Larry died in the late 1990s. They had sold Larry’s Club a few years earlier, and Rusty sold the Maverick shortly after Larry’s death.

In the decades between their daughters’ teens and their own declining years, Rusty and Larry remained active in the community and in the lives of their growing family.

Proponents of statehood, they accepted the opportunity in March 1958 to appear on Edward R. Murrow’s television newsmagazine “See It Now” and discuss their views. A CBS-TV crew came to the Lancashire homestead and filmed Rusty and Larry, in their work clothes, plugging the positives of Alaska joining the union.

Five years later — four years after Alaska’s statehood bid had been accepted — another famous television newsman, NBC’s David Brinkley, visited Alaska to see what life was really like in America’s 49th state. Once more, cameras came to the Kenai, and Rusty once again got a chance to speak her mind.

Mostly, Rusty just summarized the homesteading journey of herself and her family. She told Brinkley that, while homesteading had definitely been a challenge, it had also been rewarding. She stressed that her family’s willingness to work together toward common goals had made them successful.

Brinkley’s take on Alaska, however, seemed less positive. He had begun his show with these lines: “Of all the states in the union, Alaska is the biggest, coldest, emptiest, poorest and, quite possibly, the happiest. It has great natural resources, but they are too expensive to develop. For an Alaskan, it is cheaper to import oil from Saudi Arabia than to pump it out of the ground under his feet.”

Shortly after the documentary footage aired in early January 1963, there was backlash — albeit not directed toward the Lancashires or any other regular Alaska residents. Many people thought the overall tenor of the program had been negative, portraying Alaskans as unable to take advantage of the riches around them.

Alaska, it was implied, would need Outside money and Outside influences to accomplish anything meaningful with its own economy.

Later in the 1960s, Larry renewed his interest in horses, in part because of his youngest daughter Abby’s fondness for them. “He didn’t know anything (about horses, at first),” Abby said. “He came from a real rich family where (only) girls got riding lessons. But then he had a daughter who was just crazy about horses since birth.”

Rusty, on the other hand, was uninterested in horses — “hated them,” said Abby — but father and daughter were avid. They used them for hunting, racing and rodeo. Now Abby Ala and married for more than 50 years, she still owns horses. She hunted with them and gave riding lessons for many years.

From the 1970s until the 1990s, Larry and Rusty ran their bars and traveled when they could. Abby and her growing family lived just down the road, but Martha lived in various parts of the state, and Lori was in California and then Arizona. In the winter, Larry liked to spend a couple months in the warm Southwest, golfing, visiting and simply relaxing.

At age 79, Lawrence Henry “Larry” Lancashire succumbed to pancreatic cancer on Dec. 26, 1997. Florence Lorraine “Rusty” Lancashire (nee Tallman) died two and a half years later, on April 11, 2000, at Central Peninsula General Hospital in Soldotna. She was 80.

They were survived by their three daughters, two of whom still live in the area. Lori, the middle sister, hasn’t lived in Alaska for decades, but she still shares ownership of some of the original homestead with her siblings.