AUTHOR’S NOTE: Of the many children who were raised in the 1940s and 1950s on isolated homesteads of the Kenai Peninsula, some stayed, some left for a while and returned, and some departed but never came back. The Lancashire sisters — Martha, Lori and Abby — were all born in the States but came as children with their parents to homestead in Ridgeway in 1948. They took varying paths after high school, but now, many decades later, they have reached a kind of consensus on the value of their homestead experience.

In the 1950s, Lori Lancashire and her sisters, Martha and Abby, had glimpsed brief but tantalizing views of the possibilities and opportunities outside of Alaska — versus what they already knew: the small, isolated populations of the Kenai, with its rough roads and its long, dark, cold winters.

In January 1953, their mother, Rusty Lancashire, took the girls to Illinois to visit her relatives. Weeks later, when Rusty’s husband, Larry, retrieved his family at the Anchorage airport and drove them home, his trip over the narrow, winding, icy Seward and Sterling highways took him longer than Rusty and the girls’ flight from the Midwest.

Even then, as a young girl, Lori was beginning to weigh her options. On other homesteads on the Kenai, other boys and girls were doing the same: Stay home in Alaska or go to the Lower 48 and see what happens?

“When I was 6 or 7,” recalled Lori (now Mackstaller) recently, “Mom and I were driving into Kenai. It was a beautiful winter day. The trees looked like they were full of diamonds. I turned and said to Mom, ‘When I am old enough, I will leave Alaska and never come back.’ Her response was, ‘You will be back.’ I am not sure why I knew I would leave. I think it was wanting more choices. It seemed to me that your choices in the ’50s-’60s in Alaska were limited.”

“Lori,” said Martha, “liked to stress how different she was from the rest of us. (She would say,) ‘When I am finished with high school, I am going to go Outside.’ She wanted to be a nurse, and she did it.”

Legacy

In 1964, at age 18, Lori left the homestead and Alaska. “I started in Seattle,” she said. “I saw big, thick trees! Lights! Choices! I was there for several days, then flew to Phoenix, Arizona, to start nursing school. Dad had, and still has, family in Phoenix…. I arrived in August — 108 degrees! Disembarked on the tarmac. I looked very cute in my Playtex living girdle, lightweight wool jumper and trench coat. My uncle said he never saw someone take off clothes so fast, and never put them on again.”

As prepared mentally as she had been for this move, leaving Alaska wasn’t without a struggle. “I was homesick, missed snow at Christmas!” she said. “But I adjusted. What I didn’t realize then but now understand is that homesteading makes you extremely independent, outspoken and willing to take risks.” She overcame her homesickness and forged ahead.

After nursing school, Lori ran a pediatrics department in Phoenix for a year, and then, at her mother’s bequest, she returned to the Kenai. She worked at the medical clinic in Soldotna for a few months, and she also met her husband-to-be, a young Alaska State Trooper named David Ulfers.

Ulfers wanted to go to college, so they moved to California, where he attended classes, she worked again in pediatrics, and they became first-time parents. Their next stop was Fresno, Arizona, so her husband could work on a master’s degree. There, Lori ran a neonatal and cardiothoracic I.C.U. and became a mother for a second time.

Then they moved to Tucson so Ulfers could work on his doctorate. Lori was hired at the University of Arizona medical center to run the coronary care unit.

“My first husband divorced me after nine years (of marriage),” she said. “I remarried (to) a man with two children.” Lori worked as a nurse for 20 years and performed considerable charity work, including as chair of Angel Charity for Children, Inc.

But her ambitions propelled her forward. Despite being assured, at age 47, that she was too old to start medical school, she became determined to become a doctor. “Mom and Dad taught us to never give in, never give up,” she said. And she did not.

She graduated medical school at age 51 and completed her residency at 54. She went on to work nearly two decades as a primary-care physician in the university’s cardiology department, retiring only a few years ago. She is now 77.

Abby, on the other hand, “always knew she was going to be a farmer, and just be her own boss,” said Martha. Although Abby also owns part of the old Lancashire homestead, her current residence, her family and her Ridgeway Farms business are just down the highway on a portion of another old homestead, the one filed on in the late 1940s by Miriam “The Old Goat Woman” Mathers.

Abby and her husband, Tinker (Harry Ala), have been married over 50 years. They have seven children and numerous grandkids. Now 75, Abby can usually be found tending to the many animals on the farm or working in a greenhouse or garden.

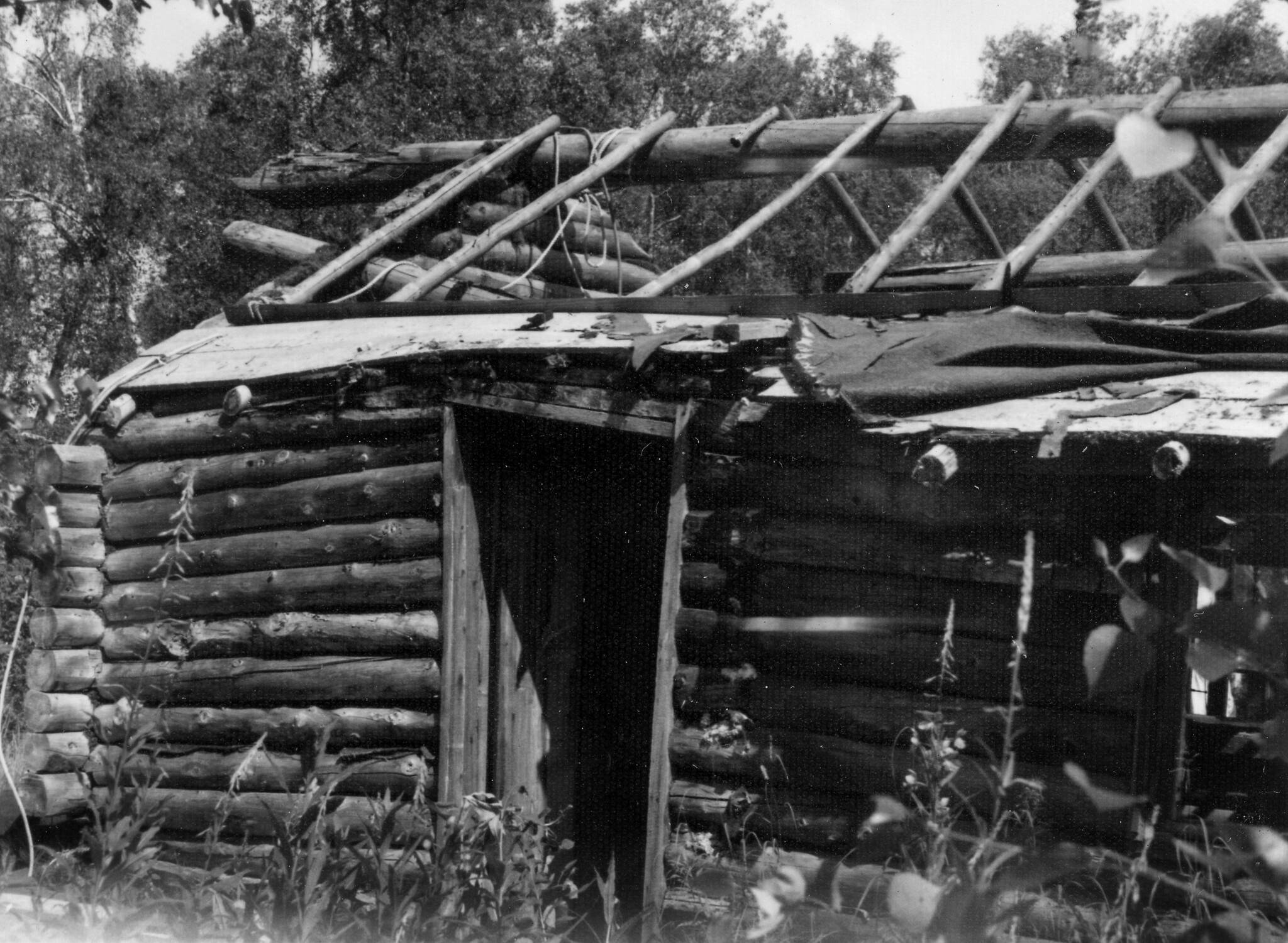

Martha, now 80, is the only sister still living on the original homestead. In fact, the core of the house she has shared for many years with husband Don Merry was the frame house her father built in the late 1950s. It stands just a short distance away from the site of the cabin in which she and her sisters were raised.

Like Abby, Martha is a farmer, although for her it has not been a life’s work. She and daughter Amy Seitz, along with daughter-in-law Jane Conway, own and operate Lancashire Farm and in 2022 were named Alaska’s “Farm Family of the Year.”

Martha said that after she completed college and got married the first time, she planned to “have a passel of kids and follow my husband to wherever he wanted to live.” This mind-set carried her to Fairbanks and produced five children before she returned to the Kenai; her second marriage resulted in two more children and took her and husband Don to Cordova and Anchorage before coming back to the homestead.

Martha and Abby — unlike their parents, who rarely attended church — are both devout Mormons. Abby said her mother once told her that if Abby hadn’t gone off and joined “that” church, she could’ve been running Rusty and Larry’s business in Soldotna, The Maverick Saloon.

Recalling her mother’s pronouncement years later still prompts a chuckle from Abby, as any affiliation with a bar was and is far from her life’s ambition.

Lori, on the other hand, does not attend church. She does, however, still feel a special kinship with the homestead. “Martha and I jointly own the land she is living on,” said Lori. “Why do I hold onto the land? Because it’s home.”

And, in the end, she said, she intends to return home.

Martha has a small cemetery on the homestead; its occupants include the sisters’ parents, two other family members, and a family friend.

Abby says she is uncertain where her own final resting place will be, but Martha is certain about her own. She plans to be buried on the homestead cemetery.

And so does Lori. “My children know,” she said. “Just cremate me and take me back to the homestead.”